Scientists chased a falling spacecraft with a plane to understand satellite air pollution

"The event was fainter than we expected."

A dramatic aircraft chase of a falling spacecraft has provided new insights into the fiery processes that accompany the atmospheric demise of retired satellites. The measurements will help scientists better understand how satellite air pollution affects Earth's atmosphere.

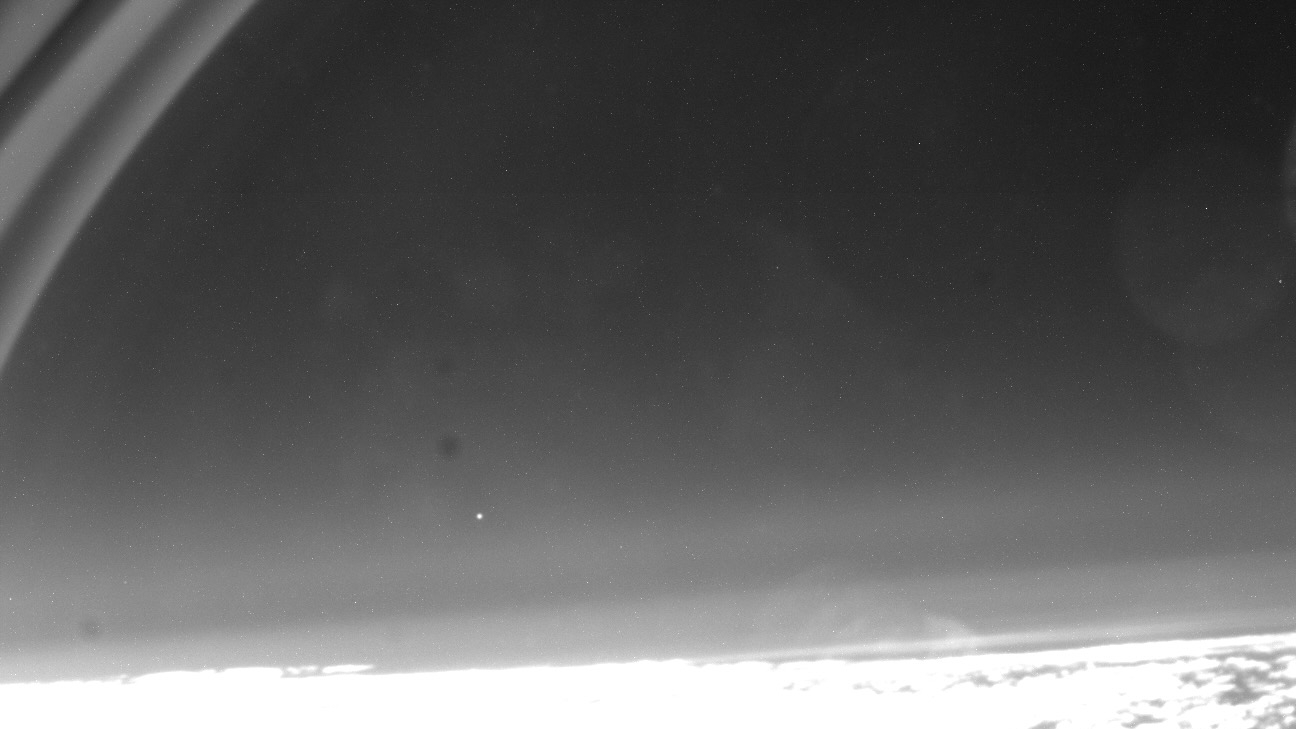

In early September last year, a team of European scientists boarded a rented business jet on Easter Island to trace the atmospheric reentry of Salsa, one of the European Space Agency's (ESA) four identical Cluster satellites. The aircraft was fitted with 26 cameras to capture the brief occurrence in different wavelengths of light.

The first results from the unique observation campaign were released in early April at the European Conference on Space Debris in Bonn, Germany.

The satellite burn-up, a meteor-like event lasting less than 50 seconds, took place above the Pacific Ocean shortly before noon local time on Sept. 8, 2024. Bright daylight complicated the observations and prevented the use of more powerful instruments, which would have provided more detailed views. Still, the team managed to gain new insights into satellite incineration, something that is little understood and hard to study.

"The event was rather faint, fainter than we expected," Stefan Löhle, a researcher at the Institute of Space Systems at the University of Stuttgart in Germany, told Space.com. "We think that it might mean that the breakup of the satellite produced fragments that were much slower than the main object and produced less radiation."

Following the initial breakup at an altitude of about 50 miles (80 kilometers), the researchers were able to record the fragmentation for about 25 seconds. They lost track of the fading streak of fragments at an altitude of about 25 miles (40 km). Using filters of different colors, the team was able to detect the release of various chemical compounds during the burn-up, which provides hints about the nature of the air pollution that arises during the satellite incineration process

"We detected lithium, potassium and aluminum," Löhle said. "But at this stage, we don't know how much of it ends up in the atmosphere as long-term air pollution and how much falls down to Earth in the form of tiny droplets."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Satellite reentries are a growing concern for the global atmospheric science community. Satellites are made of aluminum, the incineration of which produces aluminum oxide, also known as alumina. Scientists know that alumina can trigger ozone depletion and alter Earth's ability to reflect sunlight, which, in turn, could alter the atmosphere's thermal balance.

With the increase in satellite launches, many more satellites are falling back to Earth. Whatever byproducts arise during the atmospheric burn-up will likely keep accumulating high above Earth in the coming years. The effects of this satellite air pollution, however, are not well understood. The altitudes at which satellites disintegrate are too high for meteorological balloons to reach but too low for satellites to sample.

Aircraft chases, such as the one that traced the Cluster Salsa reentry last year, provide the best chance to gather accurate data on the chemical processes unfolding during those events. Such campaigns, however, are rather costly and difficult to execute. So far, only five spacecraft reentries have been tracked from the air; the previous cases included an Ariane rocket stage and three International Space Station resupply vehicles.

"Right now, researchers that model these events don't really know what happens during the satellite fragmentation," said Löhle. "That's the first thing we need to answer. We want to make sure that nothing falls on people's heads. Then we need to find out how harmful this stuff is for Earth's atmosphere."

The data captured by Löhle and his colleagues suggest that the titanium fuel tanks from the 1,200-pound (550 kilograms) Cluster Salsa may have survived the reentry and likely splashed into the Pacific Ocean. This is an important piece of information. On average, three satellites fall back to Earth every day, according to a report released by ESA last month.

Most of these satellites belong to SpaceX's Starlink megaconstellation. While the first generation of Starlinks weighed only about 570 pounds (260 kg) each, the current "V2 mini" variant of the satellite has a mass of about 1,760 pounds (800 kg). The planned V2 version will be even larger, weighing 2,750 pounds (1,250 kg). Although SpaceX claims the satellites are designed to burn up completely, the company previously acknowledged that some remnants might occasionally make it all the way down to Earth's surface.

The European team continues analyzing the data and hopes to align their observations with computer models, which could provide further insights into the progression of events during satellite fragmentation and subsequent incineration.

"We are comparing what we have seen with models of satellite fragmentation to understand how much mass is being lost at what stage," Jiří Šilha, CEO of Slovakia-based Astros Solutions, which coordinated the observation campaign, told Space.com. "Once we have an alignment between those models and our observations, we may be able to start modelling how the melting metal interacts with the atmosphere."

Löhle explained that researchers so far have too little understanding of the incineration process to be able to estimate how much satellite reentries affect the atmosphere. The disintegrating aluminum body of a reentering satellite melts, forming large droplets of molten metal. Some of these droplets vaporize into aluminum oxide aerosol, while others scatter and cool down, eventually drifting to the ground in the form of nano- and micrometer-sized bits of aluminum. The aluminum that turns into aerosol is what then triggers the ozone depletion and other climate effects.

"We don't have the data yet to be able to say how much of it turns into the aerosol," Löhle said. "We hope that, at some point, we will be able to recreate a fragmentation sequence and say how much aluminum each of the subsequent explosions released into the upper atmosphere."

The researchers hope to gather more data when Cluster Salsa's three siblings — Rumba, Tango and Samba — reenter in 2025 and 2026. The satellite quartet has circled Earth since 2000, measuring the planet's magnetic field and its interactions with the solar wind.

All those reentries, however, will also happen during daytime, which means the researchers won't be able to obtain spectroscopy measurements, which could reveal the chemical processes in the fragmentation cloud in better detail. Spectroscopy is an observation method that breaks incoming light into individual wavelengths. The signal from a reentering spacecraft, however, is too weak and gets drowned out by the bright solar light.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.