Mysterious 'Galaxy X' Around Milky Way May Soon be Found

A dwarf galaxy that is too dim to see but is suspected to orbit our own Milky Way may soon be revealed using a new mathematical technique that analyzes the ripples of gas in spiral galaxies.

The new method was developed by Sukanya Chakrabarti, a post-doctoral fellow and theoretical astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley. She thinks it can be used to detect the hypothetical so-called "Galaxy X" near the Milky Way.

The model may also have applications for detecting mysterious and as-yet inexplicable dark matter, which is thought to make up the bulk of the universe.

"My hope is that this method can serve as a probe of mass distribution and of dark matter in galaxies, in the way that gravitational lensing today has become a probe for distant galaxies," Chakrabarti said in a statement.

Chakrabarti will present the details and findings of these tests at a presentation at the 217th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, Wash.

Searching for Galaxy X

Chakrabarti predicted the mass of Galaxy X to be one-hundredth that of the Milky Way itself.

The galaxy currently sits across the Milky Way somewhere in the constellations of Norma or Circinus, just west of the galactic center in Sagittarius when viewed from Earth, based on the calculations by Chakrabarti and her colleague Leo Blitz, a professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Chakrabarti compared her prediction of Galaxy X with previous arguments for a Planet X beyond the orbit of Neptune.

In the 19th century, what would have been at that time a ninth planet was proposed by famed astronomer Percival Lowell, but the prediction turned out to be based on incorrect measurements of Neptune's orbit.

In fact, Pluto and other objects in the Kuiper Belt, where the planet was predicted to reside, have masses far too low to exert a measurable gravitational effect on Neptune or Uranus, Chakrabarti said. Since then, perturbations in the orbits of other bodies in the solar system have set off periodic searches for a 10th planet beyond the now "dwarf" planet Pluto.

On the other hand, Galaxy X or a satellite galaxy one-thousandth the mass of the Milky Way would still exert a large enough gravitational effect to cause ripples in the disk of our galaxy, researchers said.

Barbara Whitney, a Wisconsin-based astronomer affiliated with the Space Sciences Institute in Boulder, Colo., hopes to target Galaxy X as part of the Galactic Legacy Infrared Mid-Plane Survey Extraordinaire (GLIMPSE) conducted with the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Chakrabarti and Blitz also calculated that the predicted galaxy is in a parabolic orbit around the Milky Way, now at a distance of about 300,000 light-years from the galactic center. The galactic radius is about 50,000 light-years.

Satellite galaxies are common

Many large galaxies, such as the Milky Way, are thought to have satellite galaxies that are too dim to see.

The Milky Way is surrounded by about 80 known or suspected dwarf galaxies, researchers said. However, some of them may just be passing through, and not captured into orbits around the galaxy. The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, for example, are two such galactic satellites – both of them irregular dwarf galaxies.

Theoretical models of rotating spiral galaxies, however, predict that there should be many more satellite galaxies, perhaps thousands, with small ones even more prevalent than large ones. Dwarf galaxies, however, are faint, and some of the galaxies may be primarily invisible dark matter.

Earlier this year, Chakrabarti used her mathematical method to predict that one of these "dark" dwarf galaxies sits on the opposite side of the Milky Way from Earth, and that it has been unseen to date because it is obscured by the intervening gas and dust in the galaxy's disk.

Chakrabarti gained confidence in her method after successfully testing it on two galaxies with known, faint satellites.

"This approach has broad implications for many fields of physics and astronomy – for the indirect detection of dark matter as well as dark-matter dominated dwarf galaxies, planetary dynamics, and for galaxy evolution driven by satellite impacts," Chakrabarti said.

Blitz said the method could also help test an alternative to dark matter theory, which proposes a modification to the law of gravity to explain the missing mass in galaxies.

"The matter density in the outer reaches of spiral galaxies is hard to explain in the context of modified gravity, so if this tidal analysis continues to work, and we can find other dark galaxies in distant halos, it may allow us to rule out modified gravity," Blitz said.

Modeling satellite galaxies

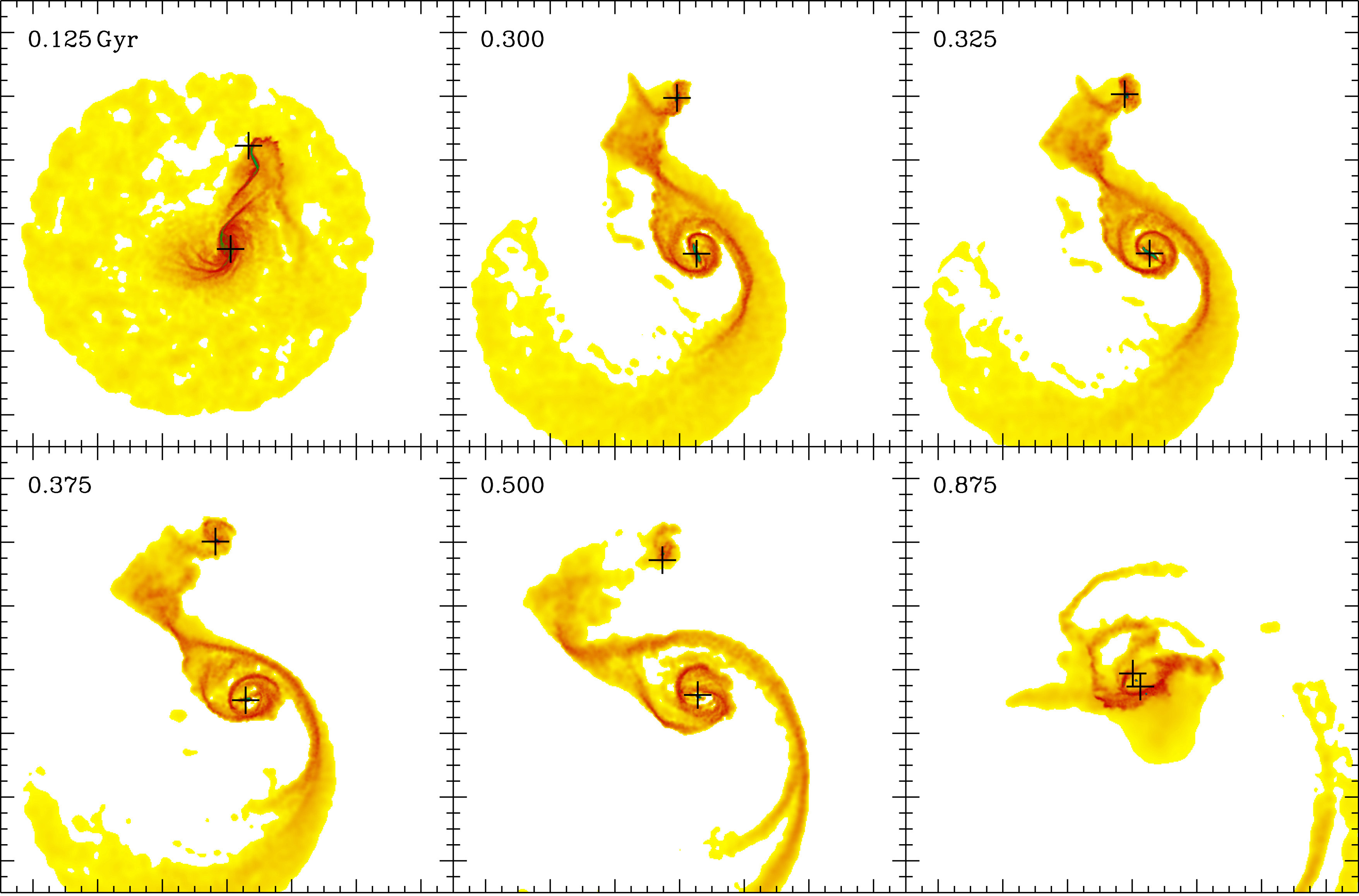

In their study, Chakrabarti and Blitz realized that dwarf galaxies would create disturbances in the distribution of cold atomic hydrogen gas within the disk of a galaxy, and that these perturbations could reveal not only the mass, but the distance and location of the satellite.

The cold hydrogen gas in spiral galaxies is gravitationally confined to the plane of the galactic disk and extends much farther out than the visible stars – sometimes up to five times the diameter of the visible spiral. The cold gas can be mapped using radio telescopes.

"The method is like inferring the size and speed of a ship by looking at its wake," Blitz said. "You see the waves from a lot of boats, but you have to be able to separate out the wake of a medium or small ship from that of an ocean liner."

The technique involves the analysis of gas distribution determined by high-resolution radio observations. Her initial predication of Galaxy X around the Milky Way was made possible by previous observations of the atomic hydrogen in our galaxy.

To test her theory on other galaxies, Chakrabarti and her collaborators used recent observations from a radio survey called The HI Nearby Galaxy Survey (THINGS), conducted by the Very Large Array, and the THINGS-SOUTH project, a sky survey performed using the Australia Telescope Compact Array in the Southern Hemisphere.

"These new high-resolution radio data open up a wealth of opportunities to explore the gas distributions in the outskirts of galaxies," said co-author Frank Bigiel, a UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow who is also co-investigator of the THINGS and THINGS-SOUTH projects.

Chakrabarti also worked with researchers at the Canadian Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics to analyze observations of the Whirlpool Galaxy (also known as M51), which has a companion galaxy one-third the size of M51. They also studied another galaxy NGC 1512, which has a satellite that is about one-hundredth the size of its galactic parent.

Chakrabarti's mathematical model correctly predicted the mass and location of these satellite galaxies.She said her technique should work for satellite galaxies as small as one-thousandth the mass of their parent galaxy.

"Our paper is a proof of principle, but we need to look at a much larger sample of spiral galaxies with optically visible galactic companions to determine the incidence of false positives," and thus the method’s reliability, Chakrabarti said.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.