Astronomers discover the earliest, hottest galaxy cluster in the universe, and it breaks all the rules

The galaxy cluster appears hotter and more mature than it should for its young age, challenging what we think we know about how these cities of galaxies form.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

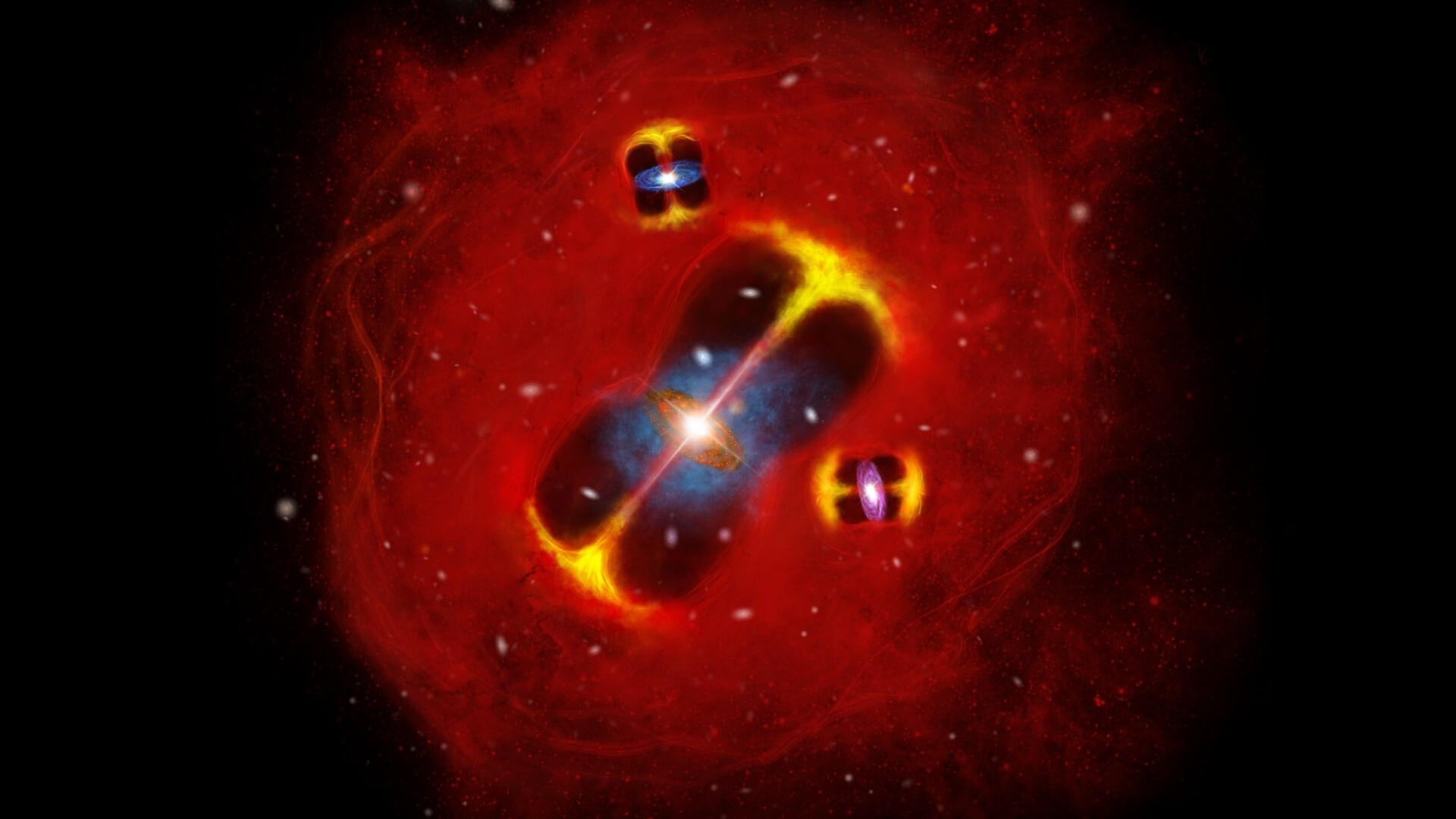

A seemingly impossible cluster of more than 30 galaxies crammed into a volume just 500,000 light-years across has been found in the universe just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang — and with a temperature that breaks all the rules.

The discovery, by astronomers using Chile's Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), of the galaxy cluster labeled SPT2349-56 challenges our understanding of how quickly galaxies and galaxy clusters were able to form.

"This tells us that something in the early universe, likely three recently discovered supermassive black holes in the cluster, were already pumping huge amounts of energy into the surroundings and shaping the young cluster, much earlier and more strongly than we thought," said Scott Chapman, a professor of astronomy at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, in a statement.

Article continues belowGalaxy clusters are filled with a fog of hot gas that we call the intracluster medium — what Dazhi Zhou, who is a PhD candidate at University of British Columbia in Canada and lead author of the paper describing the findings, refers to as a galaxy cluster's 'atmosphere'. In most clusters, the intracluster medium can reach tens or even hundreds of millions of degrees Celsius.

Astrophysicists thought that it would take many billions of years for the intra-cluster medium to grow so hot, but SPT2349-56 suggests otherwise.

"We didn't expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history," said Zhou. "This gas is at least five times hotter than predicted, and even hotter and more energetic than what we find in many present-day clusters."

The intracluster medium temperature of SPT2349-56 was measured indirectly via what's called the Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect, whereby galaxy clusters leave their mark on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, which is the leftover heat from the Big Bang. As CMB photons enter the cluster, they gain an energy boost by scattering off electrons within the intra-cluster medium. The hotter the medium, the more the electrons are moving and therefore the greater the energy boost they pass onto the CMB photons when the photons interact with the electrons. This energy boost can then be seen in the CMB corresponding to the location of a given cluster.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

More distant clusters that existed earlier in the universe than SPT2349-56 have previously been discovered. For example, in 2019 astronomers using the Gemini, Keck and Subaru telescopes identified a cluster called z660D (the number in its name refers to its redshift) that we see as it existed 13 billion years ago, 770 million years after the Big Bang. In 2023 the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) found an even earlier cluster, A2744z7p9OD, at a time just 650 million years after the Big Bang.

The difference between these clusters and SPT2349-56 is that the earlier clusters are designated 'protoclusters', meaning that they are not yet fully gravitationally bound. According to our best models of how galaxy clusters form, the gas in the intra-cluster medium becomes heated by the dynamical collapse of the galaxies into a stable, gravitationally bound state.

As such, these protoclusters do not yet have high intra-cluster medium temperatures and the models suggest that they won't reach high temperatures for many billions more years. SPT2349-56, on the other hand, seems to have rushed ahead, suggesting that our models of how galaxy clusters grow and become so hot are incomplete.

What SPT2349-56 and the earlier protoclusters all have in common is frenetic star formation. The size of SPT2349-56 is about the same as the halo of old stars and dark matter that surrounds our Milky Way galaxy, so the 30 or more galaxies that are members of SPT2349-56 are small. However, they won't remain small for long. Within those galaxies the stars are forming at a rate five-thousand times faster than in our Milky Way galaxy where on average less than ten stars form each year.

"We want to figure out how the intense star formation, the active black holes and this overheated atmosphere interact, and what it tells us about how present galaxy clusters were built," said Zhou. "How can all of this be happening at once in such a young compact system?"

For now, that question remains unanswered, but the findings so far were published on Jan. 5 in Nature.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.