Historic 1st Photo of a Black Hole Named Science Breakthrough of 2019

It was once thought impossible. Then it happened.

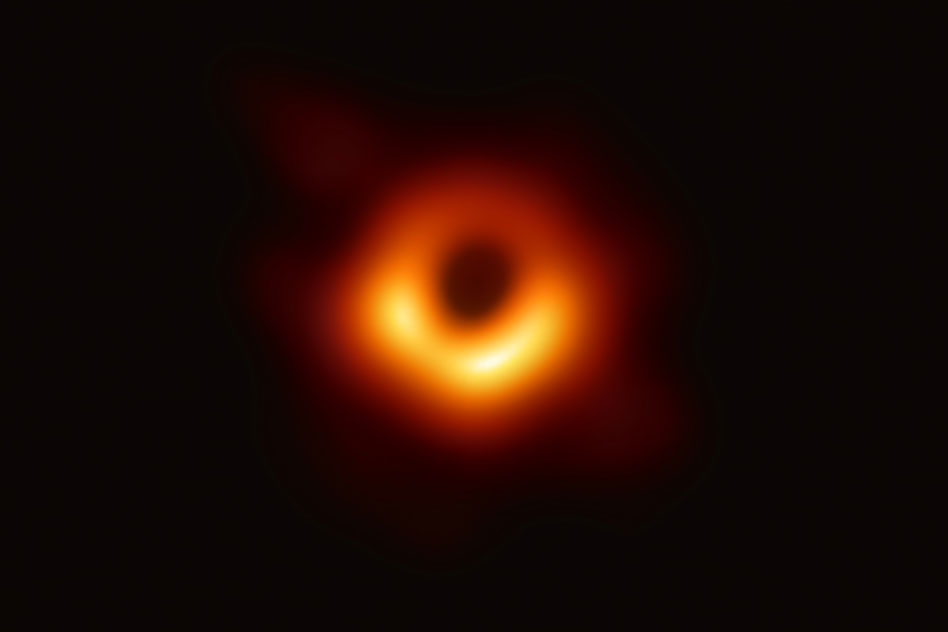

The first image of a black hole, previously thought nigh impossible to capture, was named the top scientific breakthrough of 2019 by the journal Science.

Black holes have gravitational pulls so powerful that, past thresholds known as their event horizons, nothing can escape, not even light. Supermassive black holes millions to billions of times the mass of our sun are thought to lurk in the hearts of virtually every large galaxy, influencing the fate of every star caught in their gravitational thrall.

Using Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, German physicist Karl Schwarzschild was the first to lay the foundation of the science describing black holes. In the decades since then, scientists have detected numerous signs of black holes, such as the effects their gravity have on their surroundings and the ripples in the fabric of space and time known as gravitational waves emitted when they collide.

Related: The Future of Black Hole Photography: What's Next?

Can we photograph a black hole?

Although researchers had spent years theorizing about black holes, few imagined they would ever get a chance to actually see one. Since black holes reflect no light, they are perfectly camouflaged against the darkness of space. In addition, black holes are very small by cosmic standards — for example, the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*, located in the Milky Way's core, is about 4 million times the mass of the sun but only about 14.6 million miles (23.6 million kilometers) in diameter, half as wide as the distance between Mercury and the sun.

However, about two decades ago, astronomers began wondering if they might be able to capture a photo of a black hole if it was backlit against the hot swirling gases close to its event horizon. These gases shine bright at many wavelengths of light, including ones that could pierce any murky clouds that may surround them. Scientists could then detect a dark spot against a bright background, the so-called black hole shadow.

In April, the international Event Horizon Telescope consortium revealed they successfully captured the first images of a black hole shadow. "Seeing is believing," Avi Loeb, chair of astronomy at Harvard University, told Space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Historic First Images of a Black Hole Show Einstein Was Right (Again)

Black hole photo breakthrough

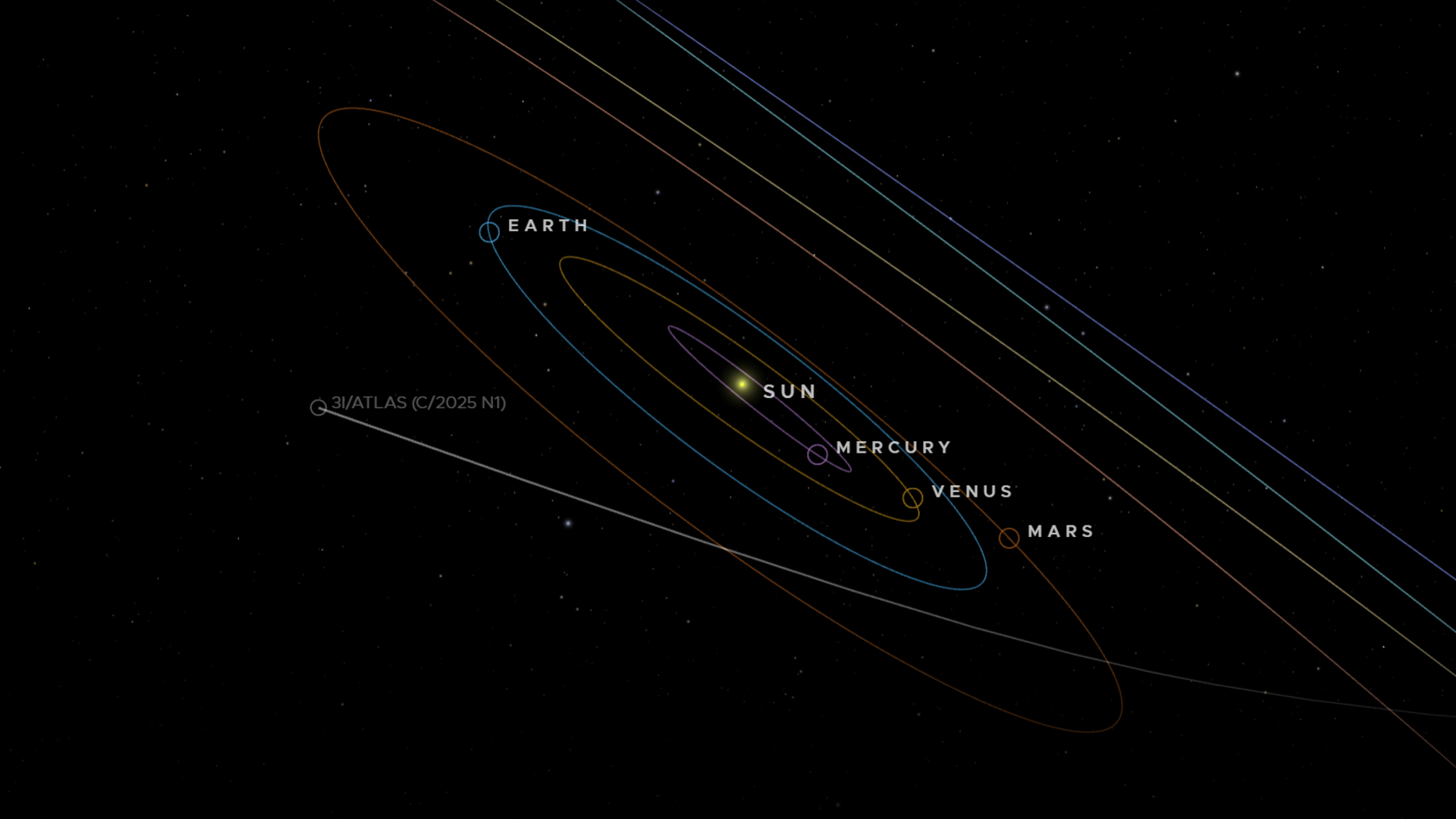

The key to this breakthrough was how the researchers linked radio dishes across the globe to create a virtual telescope effectively about the size of Earth, stretching from the United States to Mexico to Chile to the South Pole. Ultimately, they succeeded in taking a photo of the silhouette of the supermassive black hole at the center of the nearby galaxy Messier 87. Although Messier 87 is 2,000 times farther from Earth than Sagittarius A*, its central black hole is more than a thousand times the mass of Sagittarius A*, so it appears about as big in the sky — about the size as an orange on the moon.

"Having the first image of a black hole is a major breakthrough," Loeb said. "Albert Einstein and Karl Schwarzschild would have been delighted to see this image merely a century after contemplating the modern concept of black holes."

Currently, there are plans to capture images of more black holes with even greater resolution. In 2017, the Event Horizon Telescope included eight radio observatories, and three more are expected to join by 2020, boosting its power, Loeb said.

In the future, researchers hope to see explosive activity from black holes, such as when they rip a star apart or when they burst with jets of plasma traveling near the speed of light. "But most importantly, we hope to see something unexpected that would revolutionize our views on black holes and the behavior of matter near them," Loeb said.

- The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe

- Images: Black Holes of the Universe

- Black Hole Quiz: How Well Do You Know Nature's Weirdest Creations?

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us