The largest-ever simulation of the universe has just been released

"We already see indications of cracks in the standard model."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Are we living in a simulation? Well, the jury's out on that one. But humans do create simulations all the time.

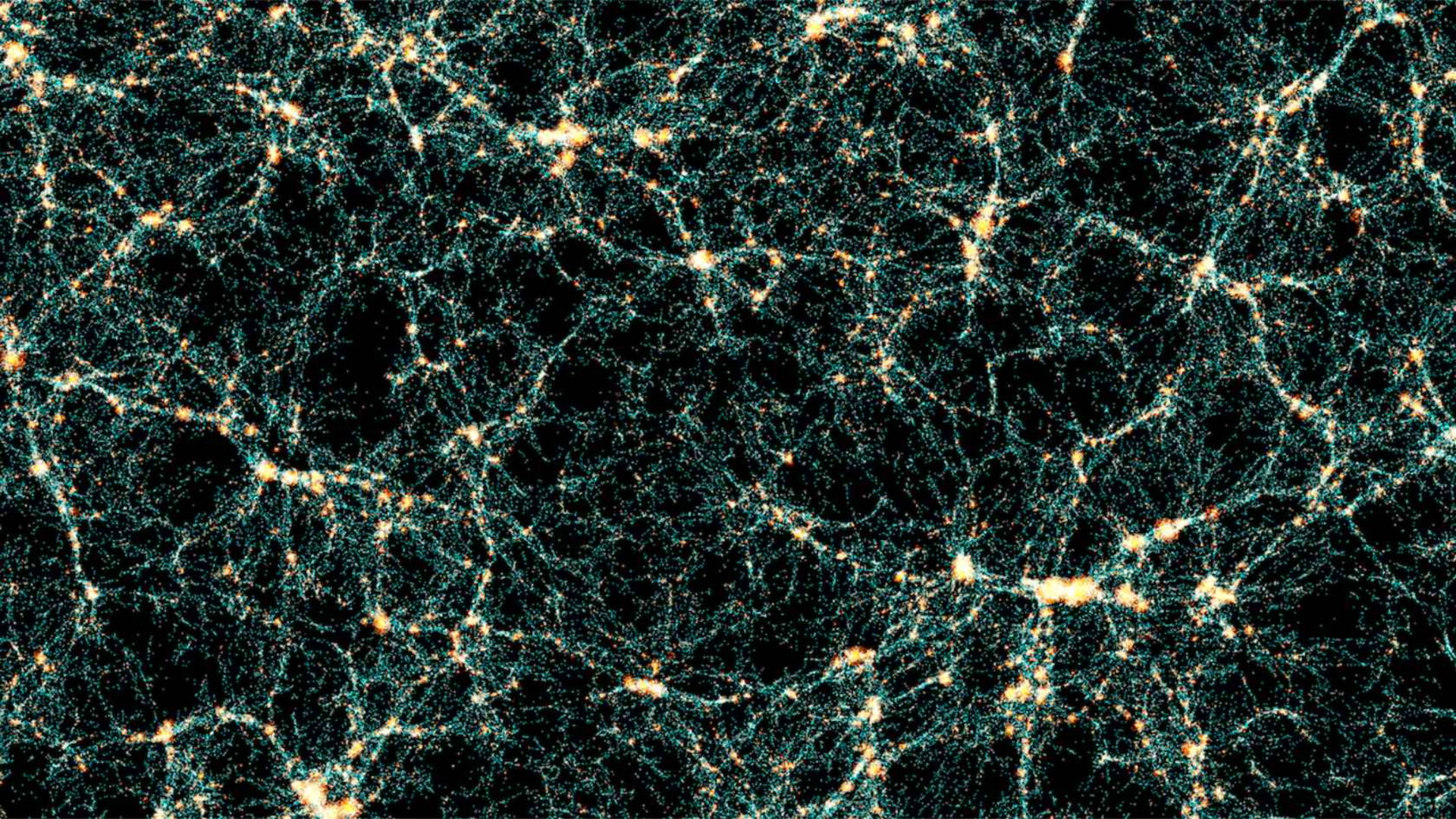

In fact, the Euclid Consortium, the international group managing the European Space Agency's Euclid space telescope, just published the world's most extensive simulation of the universe. It maps an astonishing 3.4 billion galaxies and tracks the gravitational interactions of more than 4 trillion particles.

Called Flagship 2, the simulation draws from an algorithm designed by astrophysicist Joachim Stadel of the University of Zurich (UZH). In 2019, Stadel used the supercomputer Piz Daint — then the third most powerful supercomputer in the world — to run the calculation, ultimately creating an exceptionally detailed virtual model of the universe.

"These simulations are crucial for preparing the analysis of Euclid’s data," astrophysicist Julian Adamek of UZH, a collaborator on the project, said in a statement.

Since 2023, the Euclid space telescope has been mapping billions of galaxies across the universe, studying the distribution of dark energy and dark matter. The spacecraft will eventually scan about one-third of the night sky. Given the scale of the project, Euclid produces vast quantities of data — and simulations like Flagship 2 help speed up processing times.

While the team anticipates that Euclid's observations will closely match predictions from the simulation, there are likely surprises in store. Flagship 2 runs on the standard cosmological model, which is what we currently know about the universe's composition. But missions like Euclid are designed to challenge our current knowledge. "We already see indications of cracks in the standard model," Stadel said.

The team is particularly excited to study the mystery of dark energy, the force driving the expansion of the universe. As it stands in the standard cosmological model, dark energy is simply a constant. But Euclid's observations — which will look up to 10 billion years in the past — might reveal different characteristics. "We can see how the universe expanded at that time and measure whether this constant really remained constant," said Adamek.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Euclid's first observational data was released in March 2025, with the next publication of data sets scheduled for spring 2026.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.