A mystery object is holding this 120 million-mile-wide cloud of vaporized metal together

"Stars like the sun don’t just stop shining for no reason."

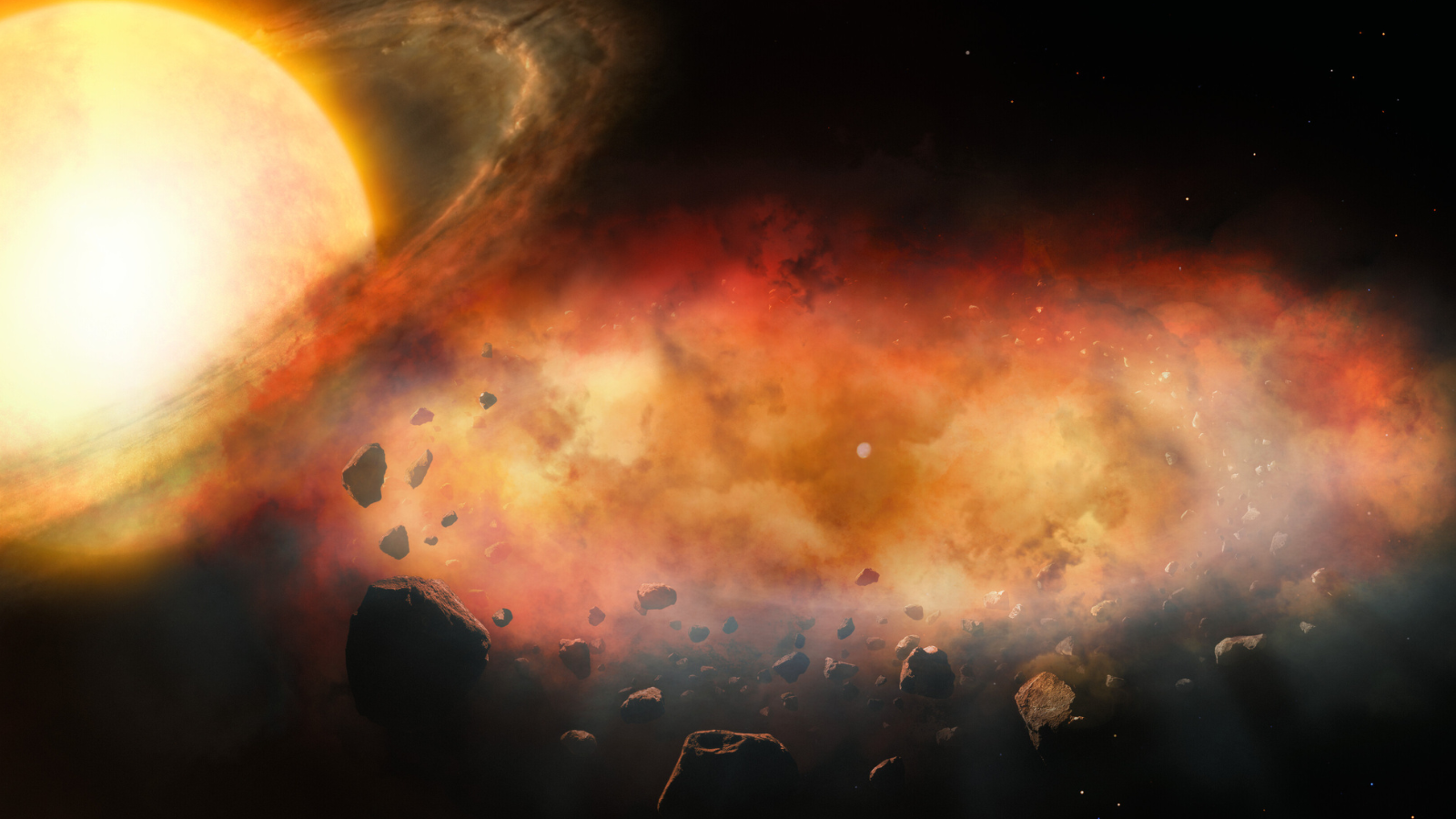

A tremendously large cloud that blocked the light from a distant star has been found to consist of swirling winds of vaporized metal. Even more curious, the cloud appears to be strangely bound to a mystery body that could be a massive planet or a low-mass star.

Astronomers were first tipped off to the existence of this metallic cloud in September 2024 when a sun-like star, designated J0705+0612 and located around 3,000 light-years away, became 40 times dimmer than usual. This dimming lasted for nine months, before the star returned to its original brightness in May 2025.

That dramatic darkening captured the interest of Johns Hopkins astronomer Nadia Zakamska, as astronomers don't typically witness such events. "Stars like the sun don’t just stop shining for no reason, so dramatic dimming events like this are very rare," Zakamska said in a statement.

Zakamska and colleagues followed up on this event using the Gemini South telescope, located on Cerro Pachón in Chile, the Apache Point Observatory 3.5-meter telescope, and the 6.5-meter Magellan Telescopes. They combined these fresh observations of J0705+0612 with archival data, finding that the star had been temporarily covered, or occulted, by a vast, slow-moving cloud of gas and dust.

The team estimated that this cloud is around 120 million miles (200 million kilometers) wide, or around 15,000 times as wide as the diameter of Earth. It is estimated to have been around 1.2 billion miles (2 billion km) away from J0705+0612 when it caused the dimming of the star. That is around 13 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

Low-mass star or high-mass planet?

The researchers also discovered that this cloud is gravitationally bound to another object, one that also orbits the star J0705+0612. That body must be massive enough to exert a strong enough gravitational influence to hold the cloud together, implying it has at least several times the mass of Jupiter, though it could be much more massive than this. That means, the big question is: what is the nature of this mystery object?

If the object is a star, then this cloud is a circumsecondary disk, a cloud of gas and dust that orbits the less massive star in a binary system. If the unknown body is a planet, then the cloud is a circumplanetary disk. The observation of a cloud of either type occulting a star is extremely rare.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To determine the composition of this cloud, the researchers turned to Gemini South's Gemini High-resolution Optical SpecTrograph (GHOST), watching for two hours as the cloud sat in front of J0705+0612.

"When I started observing the occultation with spectroscopy, I was hoping to unveil something about the chemical composition of the cloud, as no such measurements had been done before," Zakamska said. "But the result exceeded all my expectations."

The team discovered that the cloud was rich in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, which astronomers somewhat confusingly refer to as "metals." These winds of gaseous metals, including iron and calcium, were mapped in three-dimensions, marking the first time astronomers have measured the internal gas motions of a disk orbiting a secondary object such as a planet or low-mass star.

"The sensitivity of GHOST allowed us to not only detect the gas in this cloud, but to actually measure how it is moving," Zakamska said. "That's something we’ve never been able to do before in a system like this."

Mapping the speed and direction of winds within the cloud revealed to the team that it is moving separately from its host star, further confirming that it is bound to a secondary object sitting in the outer limits of this planetary system.

The team suggests that this cloud may have been created when two planets orbiting J0705+0612 slammed into each other, spraying out dust, rocks, and other debris. This kind of event is common in chaotic and young planetary systems, but is unusual for a system like this one, which is estimated to be around 2 billion years old.

"This event shows us that even in mature planetary systems, dramatic, large-scale collisions can still occur," Zakamska said. "It's a vivid reminder that the universe is far from static — it’s an ongoing story of creation, destruction, and transformation."

The team's research was published on Wednesday (Jan. 21) in the journal The Astronomical Journal.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.