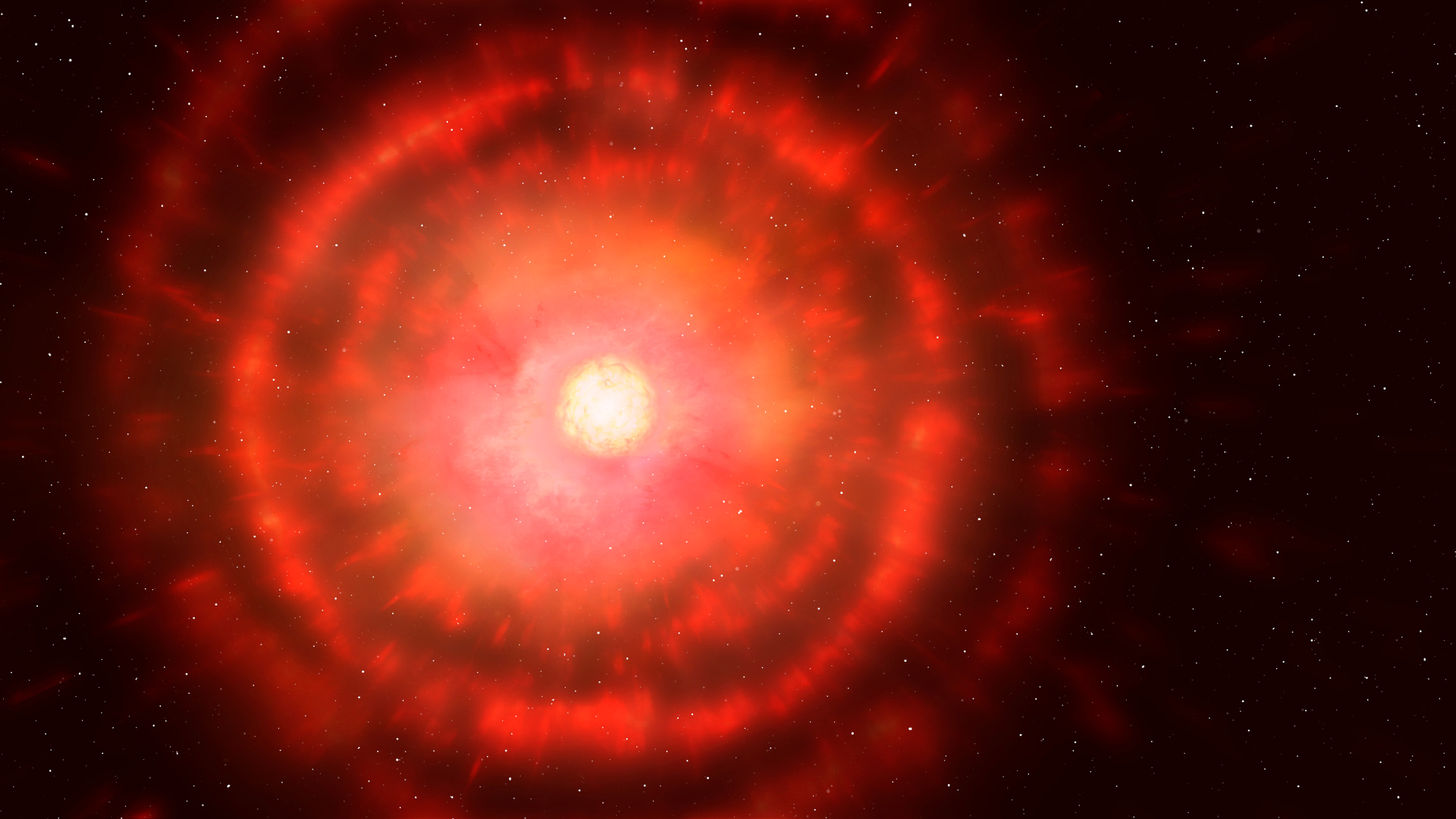

We may be witnessing the messy death of a star in real time

For over two centuries, we have watched the red giant R Leonis dim and brighten with regularity, but this 'heartbeat' is beginning to speed up near the end of the star's life.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Could a star have its own heartbeat? It sounds more like poetry than physics, but in the case of a red giant named R Leonis, the answer is a resounding, if slightly erratic, yes.

For over two centuries, we have watched this star. R Leonis is a Mira variable, a type of aging star that pulsates like a rhythmic, celestial heart. It expands and contracts, dimming and brightening with a regularity that makes it a favorite observing target for backyard astronomers and professional researchers alike. We thought we had its rhythm figured out — a little wobble here, a slight drift there, but mostly a steady, predictable drumbeat in the constellation Leo, the Lion.

But a recent analysis of 200 years of data has revealed that this cosmic heart is beginning to beat faster.

In a new paper accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and available as a preprint via arXiv, researcher Mike Goldsmith dove into the historical records of R Leonis. By combing through the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) archives, Goldsmith tracked the star's brightest and dimmest points across more than two centuries. The result? This old star is changing.

The most shocking finding is that the star's fundamental pulse, which is the time it takes to go from bright to dim and back again, has shortened by about three days since the early 1800s. In the grand scheme of a star's life, three days might seem insignificant. But for a star that usually sticks to a strict schedule, it is a foundational shift. It is the stellar equivalent of your formerly consistent resting heart rate suddenly picking up speed for no apparent reason.

So, what does the faster pulse mean?

The paper suggests we are witnessing the actual, real-time evolution of a star. R Leonis is an oxygen-rich Mira variable, a massive star nearing the end of its life. As it burns through its final reserves of fuel, its internal structure shifts. But the period shortening isn't just a straight line. Goldsmith found clear modulations — long-term cycles of change — on timescales of roughly 35 and 98 years. It appears that the star has multiple overlapping rhythms, like a drummer trying to play three different time signatures at once.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And then there's the dust.

We have always known that these stars are messy creatures. They cough up huge clouds of soot and gas into space, creating a circumstellar disk. Goldsmith noticed something perplexing: The star's dimmest moments show a strange coherence; they stay at a very similar brightness for decades, before shifting. This finding suggests that the dust shells surrounding R Leonis aren't just drifting away sluggishly; they are evolving, thickening and thinning in ways that fundamentally change how we see the star.

The paper relies heavily on historical observations, and while the AAVSO data offer useful historical context, measuring a star's brightness by the naked eye in the year 1820 is a bit different from using a modern CCD camera on a state-of-the-art telescope. There is always a chance that some of these modulations are artifacts of how we observe, rather than indications of how the star behaves.

But if Goldsmith is right, R Leonis is giving us a front-row seat to the messy, beautiful death of a star. It isn't a quiet exit; it is a series of fits and starts, a dance that is slowly accelerating as the star prepares for its final act.

As more data flow in from the next decade of digital surveys, we might finally understand if this period shortening is a permanent trend or just a passing phase. For now, the "heart of the lion" beats faster. It is enough to keep us watching.

Paul M. Sutter is a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University, host of Ask a Spaceman, and author of How to Die in Space.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.