'Hard-Rock Excavation' Begins for Giant Magellan Telescope in Chile

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The construction of a gigantic new telescope has kicked into high gear in the Chilean Andes.

The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) has now entered the "hard-rock excavation" phase, which will make way for the huge structure's foundations, leaders of the $1 billion project announced on Tuesday (Aug. 14).

Construction services company Minería y Montajes Conpax (known as Conpax) is performing the work at the telescope project site, which is part of Las Campanas Observatory in northern Chile, Giant Magellan Telescope Organization (GMTO) Corp. representatives said. [Space.com in Chile: Giant Magellan Telescope Groundbreaking Travelogue]

Hydraulic drilling and hammering of the site is expected to take five months. The foundations that will be poured in after that will support the weight of the telescope, which is estimated to be about 1,600 metric tons (1,700 tons), according to a GMTO statement. The telescope is expected to begin operations in 2024.

"In total, we expect to remove 5,000 cubic meters [6,500 cubic yards], or 13,300 tons, of rock from the mountain and will need 330 dump-truck loads to remove it from the summit," GMTO Project Manager James Fanson said in the statement.

That newly initiated digging work will go about 23 feet (7 m) down into the rock at Las Campanas, GMTO representatives said.

When it's completed, GMT will have seven primary mirrors, which together will have a combined light-collecting surface that's 82 feet (25 m) wide. These mirrors will be supported by a steel structure, which will be placed on the concrete pier that Conpax's current excavations are paving the way for.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Las Campanas sits beneath very dark and clear skies, which provide exceptional views of the universe. GMT team members believe this location, paired with the telescope's technology, will allow astronomers to make groundbreaking discoveries in a variety of fields, from cosmology and astrophysics to astrobiology.

"The GMT mirrors will collect more light than any telescope ever built, and the resolution will be the best ever achieved," project team members wrote on the GMT website.

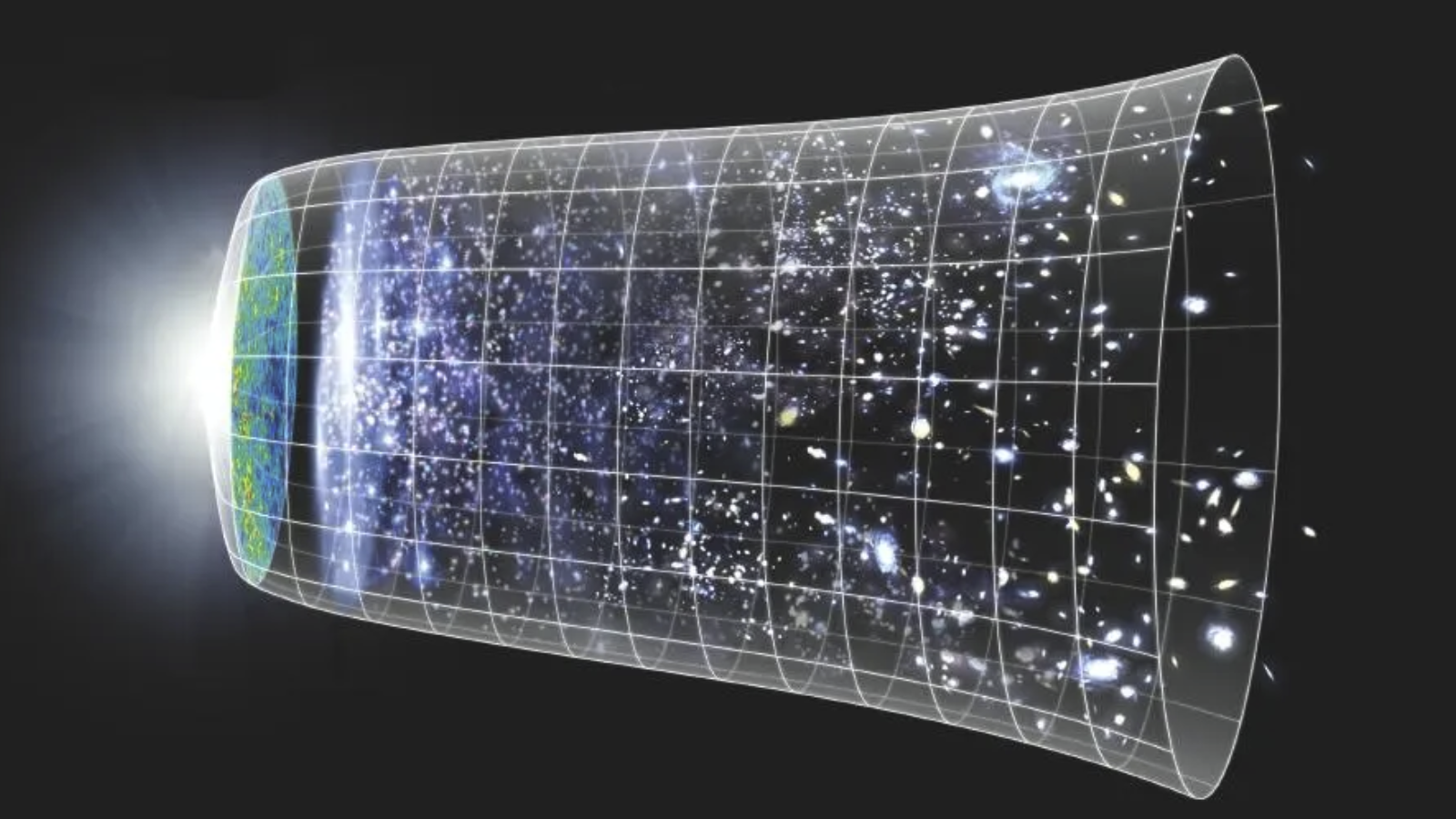

"This unprecedented light-gathering ability and resolution will help with many other fascinating questions in 21st-century astronomy," the team members added. "How did the first galaxies form? What are [the] dark matter and dark energy that comprise most of our universe? How did stellar matter from the Big Bang congeal into what we see today? What is the fate of the universe?"

GMT is named after Ferdinand Magellan, the Portuguese sailor whose voyages expanded European understanding of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. According to a 2013 GMT video, the project will similarly explore the "uncharted seas" of space. (It's worth noting, however, that local Pacific Island peoples possessed extensive navigational knowledge of the region, so Magellan was far from the first person to explore those seas. GMT's deep exploration of the cosmos will certainly be more groundbreaking.)

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter@salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.