8 Newfound Alien Worlds Could Potentially Support Life

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

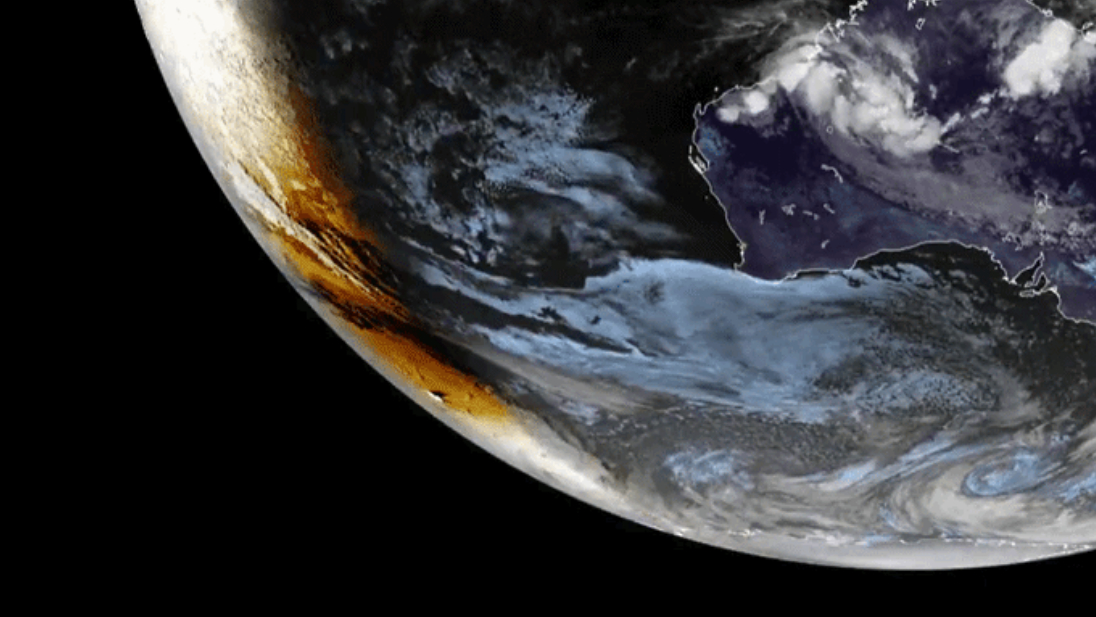

Astronomers have discovered eight new exoplanets that may be capable of supporting life as we know it, including what they say are the two most Earthlike alien worlds yet found.

All eight newfound alien planets appear to orbit in their parent stars' habitable zone — that just-right range of distances that may allow liquid water to exist on a world's surface — and all of them are relatively small, researchers said.

"Most of these planets have a good chance of being rocky, like Earth," study lead author Guillermo Torres, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), said in a statement. [10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life]

The haul doubles the number of known habitable-zone planets that are potentially rocky, study team members said.

The newly discovered worlds were all detected by NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope, then confirmed using observations by other telescopes and a computer program that assessed the statistical probability that they are bona fide planets (as opposed to false positives).

While none of the eight is a true "alien Earth," two of them — known as Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b — stand out for their similarities to our home planet (though both worlds orbit red dwarfs, stars that are smaller and dimmer than Earth's sun).

Kepler-438b, which lies 470 light-years from our solar system, is just 12 percent wider than Earth and has a 70 percent chance of being rocky, study team members said. The planet completes one orbit every 35 days and receives about 40 percent more energy from its star than Earth does from the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kepler-442b is about one-third larger than Earth, and has a 60 percent chance of being rocky. The exoplanet's orbital period is 112 days, and it gets about two-thirds as much energy as Earth, scientists said. Kepler-442b is about 1,100 light-years from Earth.

As intriguing as these two worlds are, there's no guarantee that either of them could actually host life, team members stressed.

"We don't know for sure whether any of the planets in our sample are truly habitable," co-author David Kipping, also of the CfA, said in the same statement. "All we can say is that they're promising candidates." [The Search For Another Earth (Video)]

Such hedging is unavoidable at this point, because researchers just don't have enough information. For starters, there's the uncertainty about the planets' composition, as evidenced by the estimated rockiness probabilities. (Nobody knows for sure where the dividing line lies between rocky and gaseous worlds, in terms of planet size.)

Furthermore, a planet's surface temperature is highly dependent on the composition and thickness of its atmosphere, and nothing is known about the air surrounding Kepler-438b, Kepler-442b or any of the other newfound worlds.

And some scientists employ a more restrictive definition of "habitable zone" than others. Indeed, study team member Douglas Caldwell, who presented the results today (Jan. 6) at the annual winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Seattle, said that only three of the newly confirmed planets are "securely" in the habitable zone.

But he's not discounting the life-hosting chances of the other five.

"All of these planets are small, all of them are potentially habitable — and, in fact, have a more than a 50 percent chance of being in the slightly extended habitable zone — and all are interesting," Caldwell, who's based at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, said during a AAS press briefing today.

Other big exoplanet news was announced today at the AAS meeting as well — namely, that scientists have identified 554 new planet candidates in the Kepler mission's database, bringing the number of total Kepler candidates to 4,175.

Just over 1,000 alien planets identified as potential worlds by Kepler have been officially confirmed to date, but it's likely that around 90 percent will eventually be validated, mission team members say.

Among the newly announced 554 candidates are eight that are small (between 1 and 2 times as wide as Earth) and orbit in their stars' habitable zones. Six of these eight potential planets circle a sunlike star.

"These candidates represent the closest analogues to the Earth-sun system found to date," Fergal Mullally of the Kepler Science Office said during today's AAS news conference. "This is what Kepler has been looking for. We are now closer than we have ever been to finding a twin for the Earth around another star."

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009 to determine how common Earthlike planets are throughout the Milky Way galaxy. A glitch ended the spacecraft's original planet hunt in May 2013, but researchers are still combing through Kepler's huge database. (The 554 new candidates were pulled from observations made between May 2009 and April 2013.)

And last year, Kepler embarked upon a new, two-year mission called K2, during which the observatory is searching for planets in a more limited fashion and is also studying supernova explosions, star clusters and other cosmic objects and phenomena.

Kepler has discovered more than half of all known exoplanets. The total alien-planet tally currently hovers around 1,800; the number differs slightly depending on which database is consulted.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.