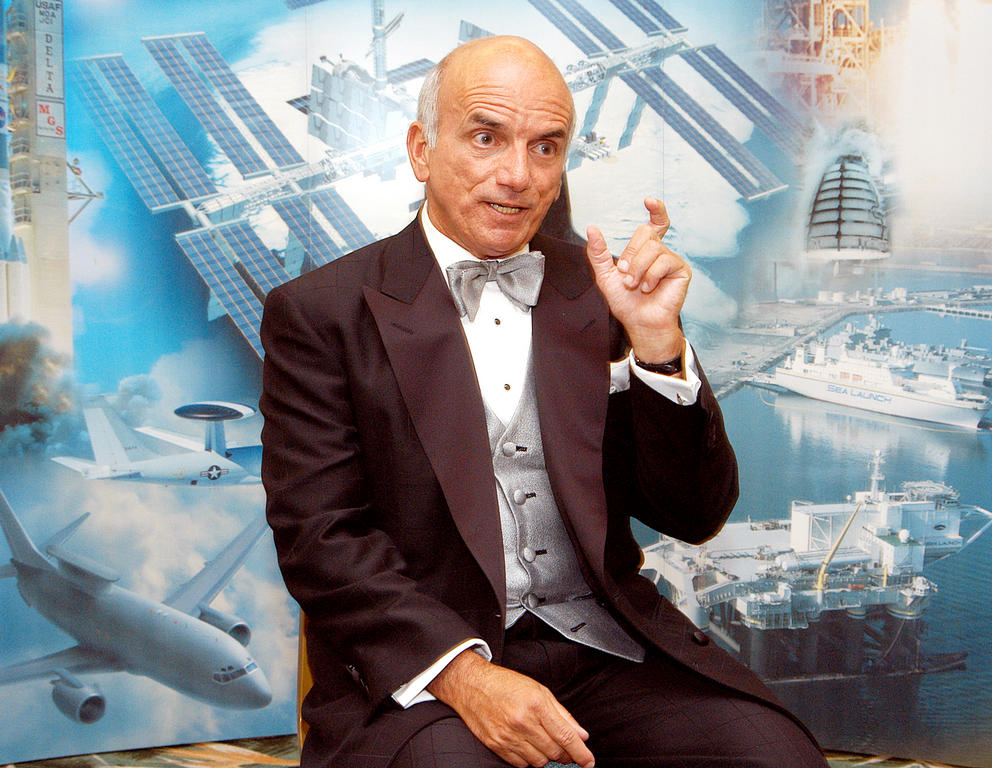

Space Tourism Pioneer: Q & A With Private Spaceflyer Dennis Tito

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This story is part of a SPACE.com series to mark a decade of space tourism. Coming tomorrow: The future of space tourism and its impact on space science.

On April 28, 2001, American businessman Dennis Tito ushered in the era of private spaceflight when he blasted into orbit aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft, bound for the International Space Station.

Tito paid a reported $20 million for his eight-day jaunt, becoming the world's first space tourist. In the process, he helped demonstrate the money-making potential of human spaceflight – potential that many different companies are now racing to tap.

As the 10th anniversary of Tito's groundbreaking flight nears, SPACE.com caught up with the space pioneer to chat about his experience -- and the prospects for private spaceflight going forward

SPACE.com: Does it seem like it's been 10 years since your flight?

Tito: It seems like a short time, because so much has happened that in my view is extremely positive in the commercial human spaceflight domain.

SPACE.com: Could you give some examples?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tito: Shortly after I flew, Mark Shuttleworth flew. Then Greg Olsen and Anousheh Ansari -- a total of seven people and eight flights. [Photos: The World's First Space Tourists]

The fact that we've now done this eight times with seven people is one important accomplishment, because it's demonstrated that it isn't just one crazy guy that decided he wanted to fly in space. There are people that are willing to make big sacrifices -- financially, putting their lives on the line and taking the time to train in Russia.

I think the success of the [Ansari] X Prize, and Scaled Composites' SpaceShipOne successfully flying suborbitally [in 2004], was a major accomplishment for a private company. And then the follow-on, with Virgin Galactic signing them up and funding the development of SpaceShipTwo. We will have suborbital commercial spaceflight, I think, within the next couple-three years at a price that people can afford. So that's the second major accomplishment.

The third major accomplishment goes beyond anything I've seen done by one person since [Soviet aerospace engineer Sergei] Korolev or maybe Wernher von Braun -- what Elon Musk has done with SpaceX. It's just absolutely incredible what he has accomplished so far. I think this is one man that we'll look back upon as being one of the greatest space entrepreneurs of all time.

Flying the Falcon 9 with the Dragon space capsule and successfully re-entering it -- he's well on the way to not only developing a cargo ship, which is almost there, but a manned craft, and that will be really our next method, other than calling upon the Russians, to transport people to space.

And the fourth [accomplishment] is politically what has been done at NASA and the administration in terms of changing the whole nature of procurement, and the way they're supporting commercial human spaceflight. I think this is probably the biggest fundamental change in NASA philosophy and government policy with regard to space in many, many decades, if not from inception. It's just mind-boggling.

I look back at those accomplishments more than I even look at my own flight as an accomplishment, because it just happened to coincide with this 10-year period.

SPACE.com: But you did help get the ball rolling in many ways. So how does it feel to be a part of that?

Tito: Well, I'm very happy that I was there, but let me clarify what really happened at that time. My dream was to fly in space before I die. And I basically came up with that lifelong goal around the time of Yuri Gagarin's flight.

So here I was, in the year 2000, and I was about to turn 60. I said, "Time is running out." I was gettting over the hill, I thought. So I said, "It's now or never." That's why I pushed so hard.

And I pushed very hard. It became kind of an obsession. I had to convince the Russians -- because I knew that was the only way to go -- that I was serious. I had to demonstrate that I was really committed to this, and I wouldn't let them down. Because they hadn't done that before -- it was all brand-new. [10 Years of Space Tourism]

And then I had to convince them I was in good physical shape, which was difficult in itself because I was 60 when I really started training. And the life expectancy of a Russian male was 57. So in their mind I'm already dead [laughs].

So that was the challenge. Now, a part of it was, I was very open to the media. I held a number of interviews on the primary channel, Channel 1 in Moscow, and I made an effort to kind of win over support. I didn't have 100 percent Russian support -- the Russian space agency was not initially as enthusiastic. The Energia people were, and the Star City people were, but the Russian space agency was a little bit tighter connected with NASA. And clearly NASA was not interested in the idea -- in fact, turned very negative on the idea.

It wasn't easy. I had to hang out in Russia for eight months without really knowing whether I was going to fly or not.

SPACE.com: So NASA made it pretty hard for you? They tried to keep this from happening?

Tito: Oh, they really tried. To their credit, though, they [have since] turned 180 degrees. And my view is, whatever hardship they caused me then, I forgive them totally.

SPACE.com: Do you think NASA's reluctance was because this was so new? At the time, they said April 2001 was a bad time for a tourist trip because there was a lot of assembly work being done on the space station.

Tito: Well, there's a whole series of theories. Remember, [would-be teacher-in-space] Christa McAuliffe was a private citizen selected by NASA to be an astronaut and tragically died in the Challenger accident [in 1986]. That was a real big blow to the nation.

It's certainly painful, but for people that are professional astronauts to lose their lives is a possibility, because that goes with the territory. But to see a private individual, this thing happen, is something else. And I think at that point, NASA decided that they weren't going to fly private citizens anymore. It was a big public relations risk, it was a big negative shock to the nation and they didn't want to go through this again. And we can understand that. That's reasonable.

I think another issue is, they were concerned about my age. If you're older, heart attacks happen, strokes happen, whatever. And what are they going to do, transport a corpse back to Earth? That would be very embarrassing for them, and traumatic.

So those are probably a couple of factors. And then, since they didn't really select me, they had no idea whether I was really qualified. They didn't know whether the Russians were just slipping me through because they needed the money, and that I was some bozo with a lot of money, and I was just going to totally screw things up when I got up there.

Well, we all know that didn't happen. To NASA's credit, they recognized that, and they immediately changed their policy to support it. And now you go 10 years, and their support is stronger than I would've ever dreamed or hoped for. They've been very supportive of private spaceflight -- the individuals flying on the station. [Spaceships of the World: 50 Years of Human Spaceflight]

So my bottom line is, I have nothing but good things to say about NASA.

SPACE.com: Once you got to orbit, what was it like? What were some of your most memorable experiences?

Tito: Well, the first thing was lift-off. The nine minutes of sheer terror that they describe? I didn’t find it that way at all, because the training was excellent.

The thing I do remember is at burnout of the third stage, which meant that we had just entered orbit -- they had pencils hanging from strings in the cabin of the Soyuz. And these pencils just started floating, and I knew it was weightless. You couldn't really tell yourself, because you're strapped in with your belts, so you didn't float at all. But I knew that we were in orbit.

And I looked out the window, saw the blackness of space, saw the curvature of Earth, and I just said, "Yes. I made it. I accomplished my life's dream." And that moment I will never forget.

SPACE.com: Only a few hundred people have ever had that view.

Tito: I was the 415th human to reach space. To me, it was a 40-year dream. The thing I have taken away from it is a sense of completeness for my life -- that everything else I would do in my life would be a bonus.

SPACE.com: Has the experience changed your life in other ways?

Tito: Well, I'm empowered by that success, by being able to accomplish it. Even though I will say I accomplished my life dream, now I have some other goals that I think I can accomplish.

I recently got my glider rating a couple of years ago, and now I'm working on two glider aircraft, contributing to the construction and planning on being a pilot, to set some world records for both speed and altitude. And, who knows? That might be accomplished some day. I think it's feasible.

SPACE.com: Would you like to go back to space? Space Adventures [the company that arranged Tito's flight] is selling seats now for a trip around the moon….

Tito: You know, I never had a goal of going around the moon, although I'd love to to that. But it's out of reach, I think, moneywise. I have to be practical. That's probably $120 million, and I'm not prepared to spend that kind of money. And, frankly, I think even if I had that amount of money sitting in the bank, I'm 10 years older now.

There is a time to hang up your boots as far as that goes. There'll be other people that can do that. I'd rather just sit back and watch them accomplish another milestone. And I'll deal with something that -- like, soaring goals that probably will broaden my experience more than repeating what I've done in the past.

SPACE.com: Do you see orbital spaceflight opening up to a lot more people in the next few decades?

Tito: I definitely do. And I think it's going to be much bigger than most people predict.

I think that we're going to see the costs, in today's dollars, of sending an individual to space for a week or whatever reduced by a major, major amount. Right now, I think it's about $50 million. It could be a million or two if we get some reusability in orbital spacecraft. I see great potential in the Falcon 9, being able to deliver people to orbit very inexpensively. [Vote Now! The Best Spaceships of All Time]

You've had close to 10 people pay large amounts of money. There aren't that many people who are worth $50 million. Now, if you lower this down to a million or two -- there are actually millions of people in the United States who are worth a million dollars.

SPACE.com: Yes, slashing the price would expand that pool enormously.

Tito: Oh, geometrically. So I think the big surprise is going to be -- not that we're not going to see thousands of people flying suborbitally, but that that's going to kind of whet the appetite. And people will say, "Oh, I flew suborbitally, I came back, I was real comfortable from a safety standpoint. I'm ready to graduate and go spend a week in orbit."

SPACE.com: Do you think it's feasible to see the price come down that much in 10 years or so?

Tito: Yes. But I may be off in time a little. I think it'll eventually get down to that price in today's dollars. It could happen within 10 years. But I think it will happen within 10 to 20 years. And if I'm wrong, it'll be $5 million -- we won't quite be there yet. But I think you're going to see a lot of people flying in 2021.

SPACE.com: It's really exciting to think about those possibilities.

Tito: It is exciting. Because as human beings, we need new challenges. And the history of our species is that, for millions of years, we've been migrating. We started in Africa, and we've been migrating in waves around the world. That's a natural part of survival.

And we're going to migrate to Mars and maybe other habitats. We're going to set up colonies. It's so ingrained in our behavior as humans to explore, and to expand and to migrate. We're wired that way, and that's why it's so satisflying.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.