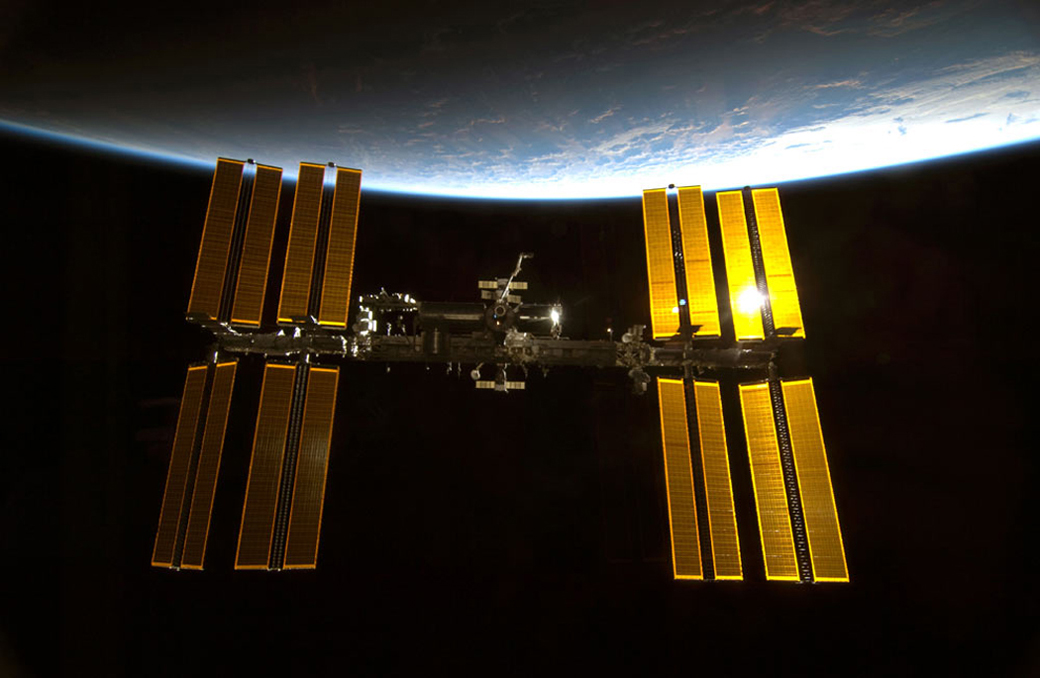

3 Private Spaceflight Companies Will Ferry Cargo to Space Station

NASA has selected SpaceX, Orbital ATK and Sierra Nevada Corp. to fly cargo to the International Space Station (ISS) starting in 2019, the agency announced today (Jan 14).

Between 2019 and 2024, NASA will purchase a minimum of six uncrewed cargo missions from each of the three companies, agency officials said in a media briefing today. The space agency has the option to purchase additional re-supply missions from any of the three providers, and will likely do so, said Kirk Shireman, program manager for the ISS.

SpaceX and Orbital ATK were selected as cargo providers in NASA's first round of Commercial Resupply Services contracts, known as CRS1; both companies have flown multiple re-supply missions to the ISS using a capsule called Dragon (SpaceX) and a spacecraft named Cygnus (Orbital ATK). [Space Station's Robotic Cargo Ship Fleet: A Photo Guide]

The new round of contracts is referred to as CRS2. Dragon and Cygnus will keep flying in the CRS2 missions, but Sierra Nevada's Dream Chaser will join them. This space plane is capable of landing on a runway, as NASA's now-retired space shuttles did; this ability will provide some unique science opportunities, NASA officials said.

Shireman said the details of why these three candidates were selected will be released soon. At least two other companies, Boeing and Lockheed Martin, had submitted proposals for the CRS2 contract as well. NASA officials did not say how much each mission would cost, but Shireman said the maximum total value of all the CRS2 contracts is $14 billion. This number, however, was set as part of a government requirement, Shireman said, adding that the actual cost of "the mix of flights that we're looking at will be nowhere near that value."

SpaceX, Orbital ATK and Sierra Nevada will each offer NASA slightly different cargo mission capabilities, Shireman said. Options from those companies include pressurized or unpressurized cargo (the former can support living scientific samples), return-cargo vehicles that either burn up in the atmosphere (Cygnus) or return to Earth for retrieval (Dragon and Dream Chaser), and vehicles that can either dock directly with the station or be grappled and berthed using the orbiting lab's robotic arm. (Berthing ports have larger openings for larger cargo, NASA officials said.)

Dragon and Dream Chaser both return to Earth after each mission is done. However, Dragon experiences "hard landings," which usually mean parachuting straight down into the ocean, whereas Dream Chaser will land more gently on a runway.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Runway landings tend to have a lower physical impact on the return cargo, and they allow for something called "accelerated pressurized return," which means the cargo can be retrieved within 3 to 6 hours after landing, said Julie Robinson, chief scientist for the ISS.

This is beneficial for experiments that include live animals or other living samples, Robinson added. When scientists want to test the effects of gravity on biological samples, for example, it is often crucial to examine the samples as soon as they return to Earth, before they start to readapt to gravity, Robinson said. In addition, gentle landings can be better for preserving delicate samples, such as crystals grown in microgravity.

Both Orbital ATK and SpaceX suffered launch failures during NASA CRS1 missions in the last 15 months, resulting in the loss of NASA cargo intended for the orbiting outpost. Orbital's Antares rocket exploded shortly after pushing off the launch pad in October 2014, and SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket disintegrated just over 2 minutes after liftoff in June 2015.

Those setbacks did not pose a threat to the lives of the crewmembers aboard the station. But NASA officials said that having a third cargo supplier available was a factor in its CRS2 decision.

"One of the considerations from an operational standpoint on the ISS, it's really important to have more than one supply chain," Shireman said. "If you lose one, you have the ability for another one being [implemented] right after it from a similar redundancy or a similar supplier."

SpaceX, along with Boeing, has also been selected by NASA to supply crew transportation to the orbiting outpost, with the first astronaut-taxi flights beginning as early as 2017.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter