Higgs Boson's Nobel Nod Marks 'Fantastic Day' for Particle Physics

The Nobel Prize in physics was awarded Tuesday (Oct. 8) to two physicists who predicted the existence of the renowned Higgs boson particle nearly 50 years ago, and scientists around the world were quick to offer their praise, calling it "a fantastic day for particle physics."

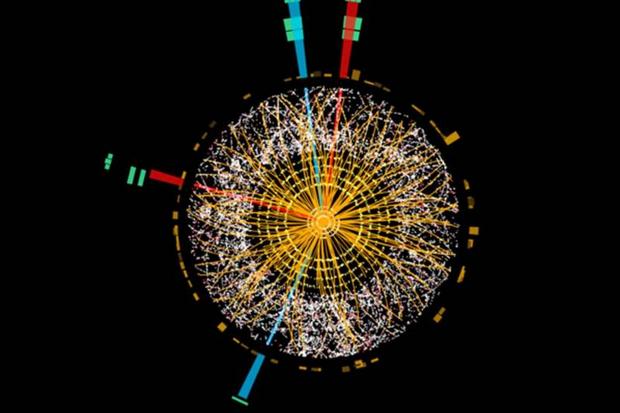

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Nobel Prize to Francois Englert, of Belgium, and Peter Higgs, of the United Kingdom, for their independent research in 1964 on the theory of particle masses. Their studies led the way to the discovery of the particle, which is thought to explain how other fundamental particles get their mass, by two experiments (dubbed CMS and ATLAS) at the CERN lab in 2012.

In the weeks leading up to the Nobel Prize announcement, Englert and Higgs were early favorites to take home this year's prestigious award. The prize honors the groundbreaking work done by the two physicists that set off a decades-long hunt for the once-elusive Higgs boson particle, said Meenakshi Narain, a professor of physics at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

"This Nobel Prize is a long time in the making," Narain, who participated in the search for the Higgs boson particle as part of the CMS research team, told LiveScience. "This is one of the crowning achievements of our field." [Top 5 Implications of Finding the Higgs Boson]

In July 2012, evidence of a new particle thought to be the Higgs boson was reported by two separate research teams — CMS and ATLAS — at CERN's Large Hadron Collider, the world's largest atom smasher. The much-lauded discovery was confirmed this past March.

The discovery of the Higgs boson particle represented the final missing piece of the puzzle predicted by the Standard Model, the reigning theory of particle physics, said Michael Turner, president of the American Physical Society (APS).

"The discovery of this new class of elementary particles not only completes one of the great intellectual achievements of the last century — the Standard Model of particle physics — but also raises new questions and has implications for other areas of physics, including the birth of the universe," Turner said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In 1964, Englert, Higgs and Robert Brout (who died in 2011) published their papers independently in the APS journal Physical Review Letters. The Nobel Committee's rules dictate that the awards cannot be given posthumously, which removed Brout from contention. For science prizes, the committee's rules also dictate that no more than three individuals can share the honor, and the prize is typically not awarded to institutions or organizations, unlike with the Nobel Peace Prize.

Still, the award recognizes the efforts of the pioneering scientists, and the decades of research that culminated in the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson particle.

"It's wonderful to see a 50-year-old theory confirmed after decades of hard work and remarkable ingenuity," Doon Gibbs, director of Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y., said in a statement.

At CERN, near Geneva, scientists celebrated the announcement. "I think we can all be proud," Rolf-Dieter Heuer, CERN's director general, told reporters in a news briefing Tuesday. "Both things go very closely together — theory and experiment. I can only say it's great. It's a fantastic day for particle physics." [Photos: The World's Largest Atom Smasher (LHC)]

Joe Incandela, a spokesman for the CMS research team, said physicists gathered at CERN to hear the announcement and were elated with the outcome.

"As experimentalists, we don't go into this expecting a Nobel Prize," he said. "For us, the prize is the discovery, so I think we're very happy that our work was directly recognized."

With the Standard Model now complete, physicists are probing other enduring mysteries that lie beyond the visible realm of the universe. These include understanding the role of gravity, and looking for signs of enigmatic dark matter and dark energy, which is the invisible stuff that makes up about 96 percent of the universe.

"With the existence of the Higgs boson confirmed, explaining why the fundamental building blocks of nature acquire mass, we can now move on to the next challenges to our understanding, such as the phenomena of dark matter and quantum gravity," Frances Saunders, president of the Institute of Physics, said in a statement.

Furthermore, the discovery of the Higgs boson particle and today's Nobel Prize announcement has cast a spotlight on the world of particle physics, and scientists now hope the publicity generates more funding amid shrinking budgets in the global economy.

"It's been really gratifying, as a particle physicist, to see how people have been so interested in the Higgs boson," Don Lincoln, an adjunct professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and a researcher at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, told LiveScience. "It's been almost NASA-level interest, and I'm hoping it will translate into recognition by the nation and the world science community."

This story was provided by LiveScience, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.