NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter to Be Farthest Solar-Powered Trip

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

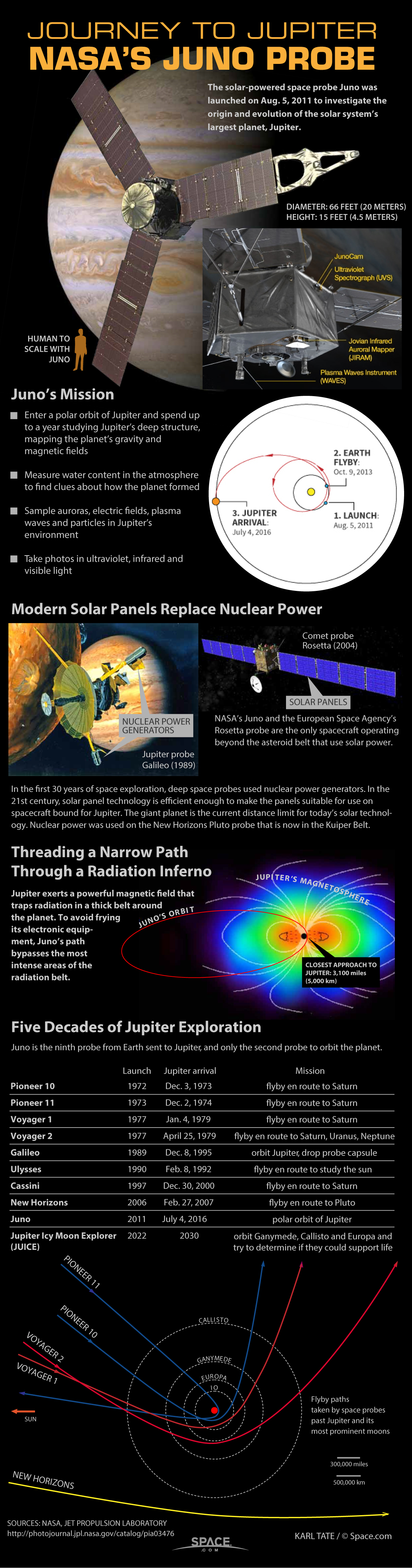

NASA's Juno spacecraft is heading for the planet Jupiter this week with a novel energy source for a deep space probe — solar power — making it the farthest robotic space traveler to run on sunlight, scientists say.

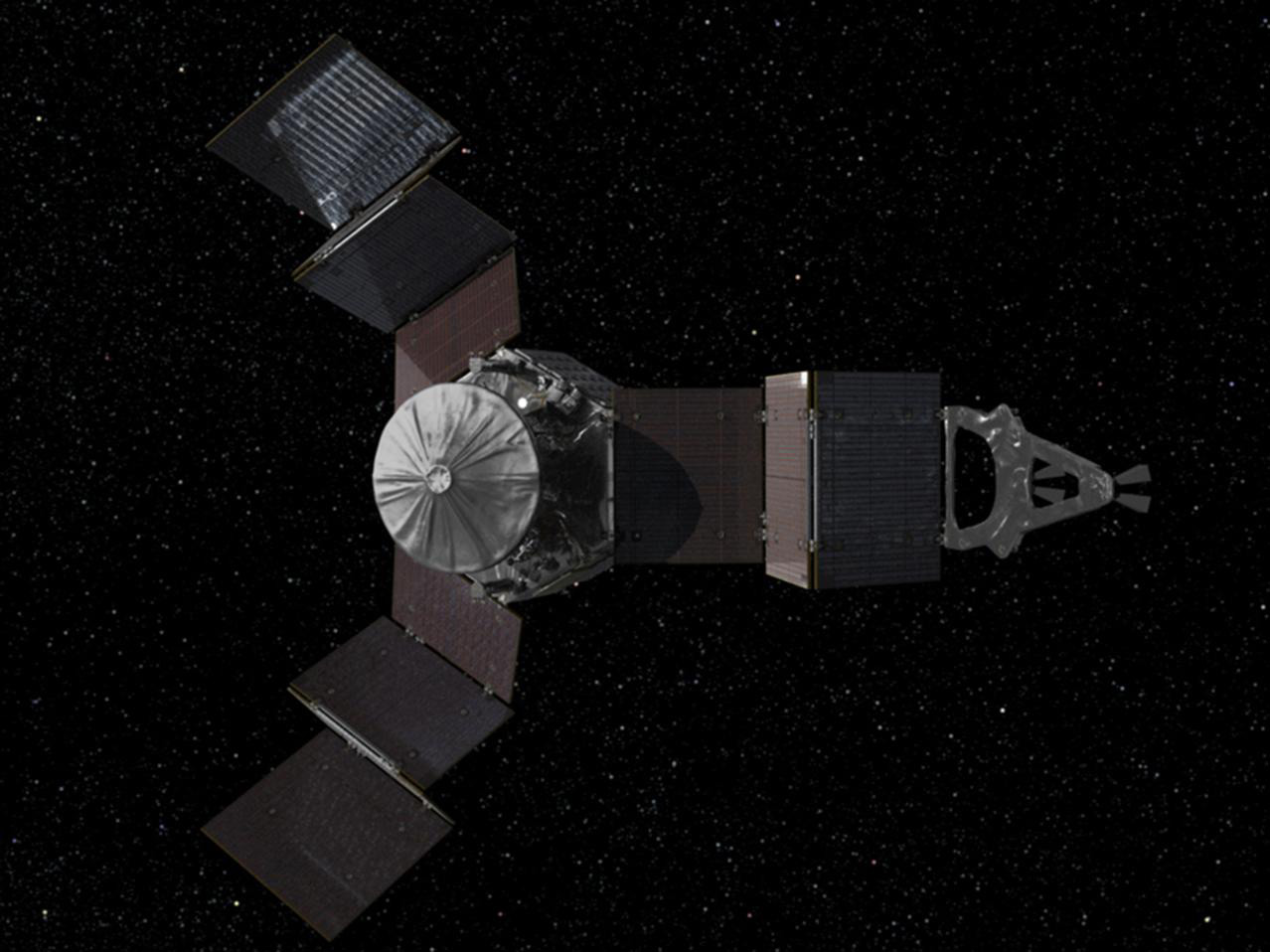

Unlike past missions to the outer planets, which carried nuclear generators to power their instruments, Juno is equipped with three huge solar wings to feed its eight Jupiter-watching instruments.

Within an hour of its planned launch on Friday (Aug. 5), the Juno spacecraft will slowly unfold its three large solar panels, each nearly 9 feet (2.7 meters) wide and 30 feet (10 meters) long. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

These panels will be the sole source of energy over Juno's five-year trip to the gas giant, as well as its year-long exploration of the planet Jupiter beginning in 2016, making Juno the most distant solar-powered craft ever.

In April 2017, after 9 months of orbiting the largest planet in the solar system, Juno will be approximately 507 million miles (816 million kilometers) from the sun. At that point, it will break the record to be set by the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft in October 2012, which will use the sun as its sole source of power as far out as 492 million miles (792 million km) on its way to visit Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Feeding off the sun

Jupiter is five times as far from the sun as Earth and it receives 25 times less light.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For years, scientists concluded solar power at such distances was too weak to support a spacecraft. The size of the panels needed to energize a far-oft vehicle would be too cumbersome, and would create a host of problems, experts reasoned. [10 Alternative Energy Bets]

When scientists started planning for Juno in 2002, they compared the feasibility of solar power with the nuclear power options available at the time.

According to principal investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Tex., both methods would have required some modifications. The team opted to utilize solar power because they felt it had the least amount of development requirements.

Bolton noted the many challenges that were identified and planned around, as the team sought methods to overcome each one.

"I say challenges, but what I'm talking about is careful engineering," Bolton told SPACE.com.

High-tech solar cells

The Juno mission uses the latest generation of solar cells, which are 50 percent more efficient than those in use two decades ago.

The nearly 19,000 cells on Juno are outfitted on three arrays the size of flattened tractor trailers. Near Earth, the solar panels will generate 14 kilowatts of electricity, but once in orbit around Jupiter they will only muster about 400 watts — enough to power a handful of light bulbs.

To operate on so little power, the scientific instrumentation and onboard computer are highly energy-efficient.

The team also had to determine an optimal course around the planet that would keep Juno in the sunlight. They devised a flight path around the poles that avoided Jupiter's shadow, as well as the high radiation belts that peak around the equator. The radiation won't be completely avoided, and will degrade the solar cells over time, but the energy put out at the end of the mission should be enough to meet the spacecraft's needs.

Solar power technology was ultimately the best option for Juno's scientific needs. But it also helps that the choice is environmentally friendly.

"We're happy to be green," Bolton said. "Of course, we were green before it was in to be green."

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky