The 15 Weirdest Galaxies in Our Universe

The universe contains somewhere in the ballpark of 100 billion and 200 billion galaxies. With numbers that large, you can bet that there are some real weirdos out there. Out beyond our Milky Way, there are galaxies shaped like jellyfish, galaxies that consume other galaxies, and galaxies that seem to lack the dark matter that pervades the rest of the universe.

Here are some of the strangest galaxies out there.

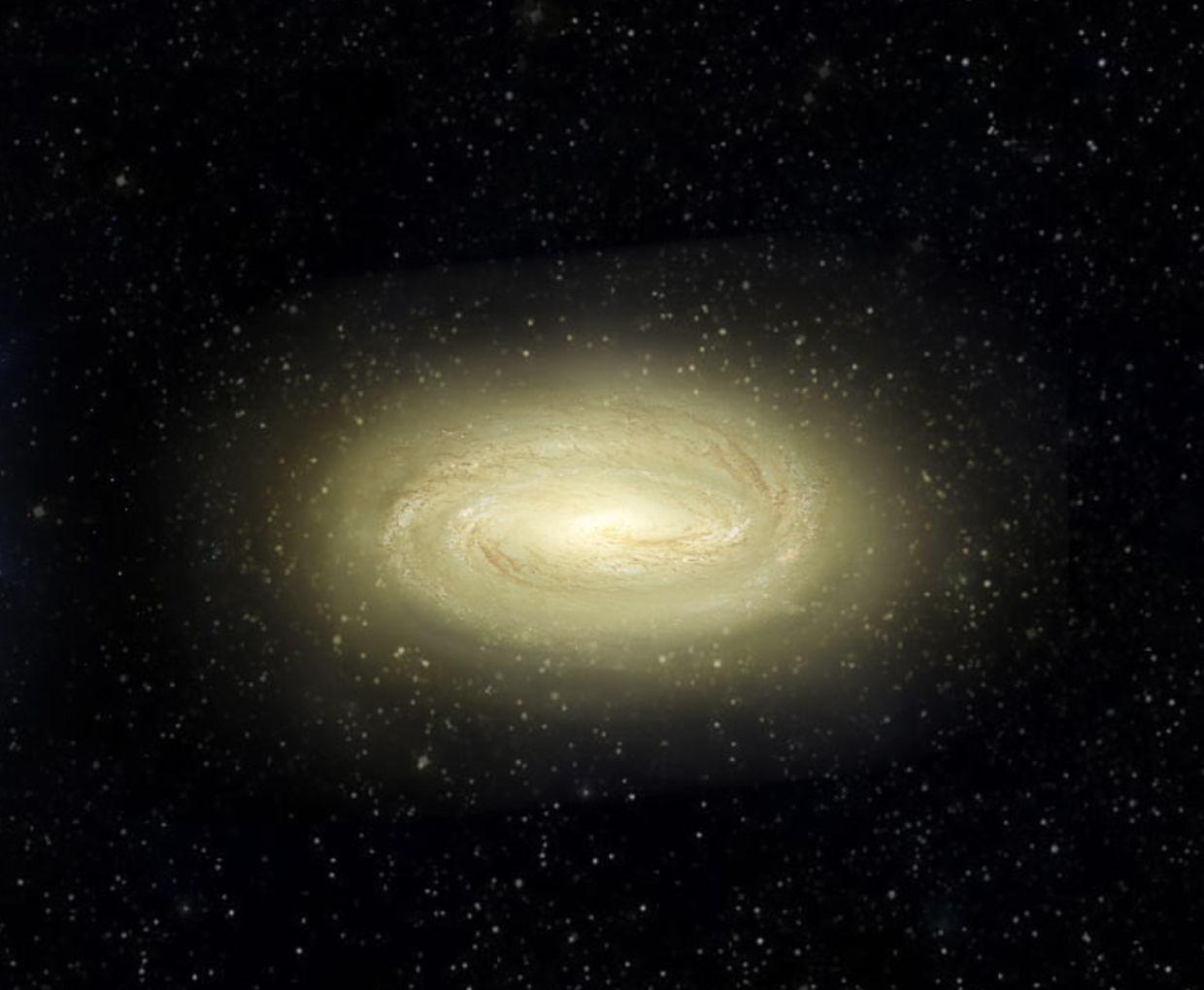

Just like a jellyfish

Located in the constellation Triangulum Australe, galaxy ESO 137-001 looks amazingly like a jellyfish swimming amid a sea of stars. The galaxy is a barred spiral galaxy — together, its stars form a spiral shape with a bar-shaped center — with a twist: streamers of stars that seem to drift like jellyfish tentacles.

According to NASA, these stars are forming inside a tail of dust and gas (invisible to the naked eye) that streams off ESO 137-001. This formation process is a bit of a mystery, as the gases in the tail should be too hot for star formation.

Missing matter?

In 2018, the Hubble Space Telescope spied something never seen before: a galaxy with almost no dark matter.

This discovery immediately raised red flags. Dark matter is a mysterious form of matter that interacts with gravity, but not with light. It makes up more of the total matter in the universe than the matter we can see, so finding a galaxy without any was bizarre, to say the least.

A year later, scientific sleuths solved the mystery: The galaxy, NGC 1052-DF2, was not 65 million light-years away, as originally believed. It's really only about 42 million light-years away, researchers reported March 14, 2019, in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. That change in distance completely alters the calculations for the galaxy's mass. Turns out, it's a pretty normal galaxy after all, and the universe (kind of) makes sense again.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Zombie galaxy

The massive, disk-shaped galaxy MACS 2129-1 spins twice as fast as the Milky Way does, but it's still not nearly as active. Hubble observations of the distant galaxy reveal that it hasn't made stars for some 10 billion years.

MACS 2129-1 is what's known as a "dead galaxy," because stars no longer form there. The discovery of this galaxy was a head-scratcher. Scientists believed that galaxies of this sort had formed by merging with smaller galaxies over time, but MACS 2129-1's stars didn't form from these sort of explosive mergers; they formed early on, in the disk of the original galaxy. The findings, published in the journal Nature in 2017, suggest that dead galaxies somehow internally rearrange their structure as they age rather than changing shape because they combine with other galaxies.

Cannibal galaxy

As if zombie galaxies weren't spooky enough, some galaxies are giant cannibals. The Andromeda galaxy, Earth's largest neighbor, has been devouring smaller galaxies for at least 10 billion years, according to 2019 research. In another 4.5 billion years, the Andromeda galaxy and the Milky Way galaxy will collide, although it's not yet clear who will devour whom in that cosmic pile-up. (Earthlings, unfortunately, will not be around to see this clash play out, as our own sun is heating up and will likely make life on Earth impossible between about 1 billion and 5 billion years from now.)

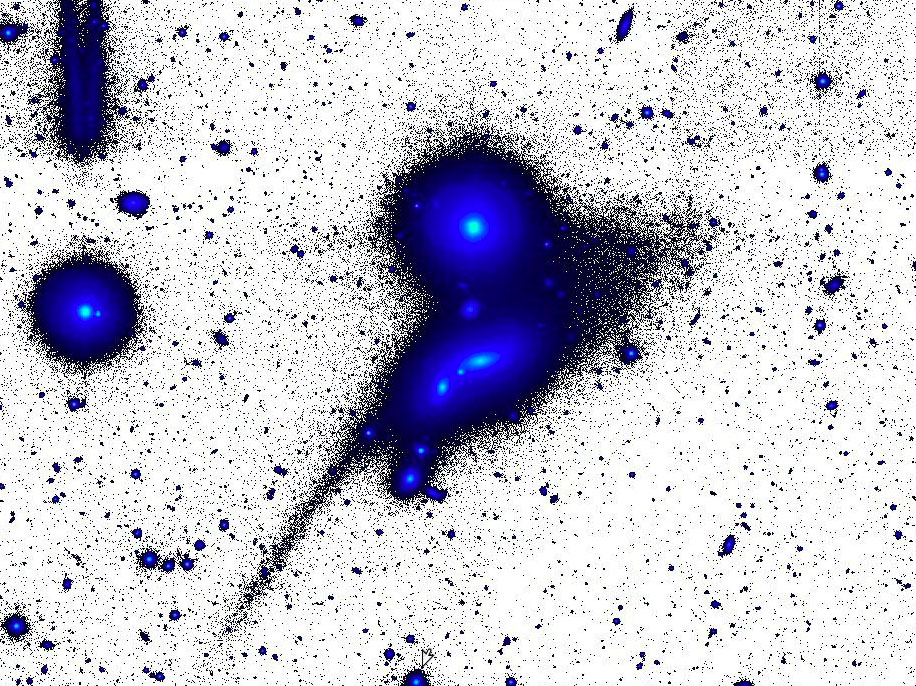

Tadpole swims through space

Three hundred million light-years away, an enormous tadpole swims through space. This "tadpole" galaxy has a tail that's a whopping 500,000 light-years long, and is 10 times longer than the Milky Way.

What created this odd galactic shape? A cosmic collision, researchers reported in 2018 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Two disk galaxies pulled on a smaller dwarf galaxy, clumping the stars on one end into a "head" and leaving the others to stream out in a long "tail." This arrangement is for a limited time only, though. In a few billion years, the galaxies will merge together with some others in the vicinity to create one single galaxy.

Luminous thief

If it isn't obvious yet, galaxies frequently interact with one another, squeezing their neighbors into new shapes, stealing stars and carrying on with other shenanigans. The brightest known galaxy in the universe is one of these thieves. In 2018, scientists announced that they'd observed the galaxy W2246-0526 sucking up half the mass of three nearby galaxies.

Astronomers were able to observe streamers of mass connecting the galaxies — at least as they were doing that more than 12 billion years ago, when that light began its journey toward Earth. The observation is the most distant direct snapshot of galactic cannibalism and the only known example of a galaxy siphoning off more than one neighbor at a time.

Doomed Little Cub

Possibly the cutest-named galaxy ever, Little Cub sits in the constellation of Ursa Major. This dwarf galaxy has been largely dormant since the Big Bang, which means that it might contain molecules unchanged since just moments after the rapid expansion of the universe 13.7 billion years ago.

Little Cub is also doomed. It's being consumed by its larger neighbor, a Milky Way-like galaxy called NGC 3359. Still, the opportunity to watch NGC 3359 strip the star-forming gases from Little Cub is valuable to science, because astronomers may be able to measure the signatures of those early-universe molecules before they're gone.

Galaxy in bloom

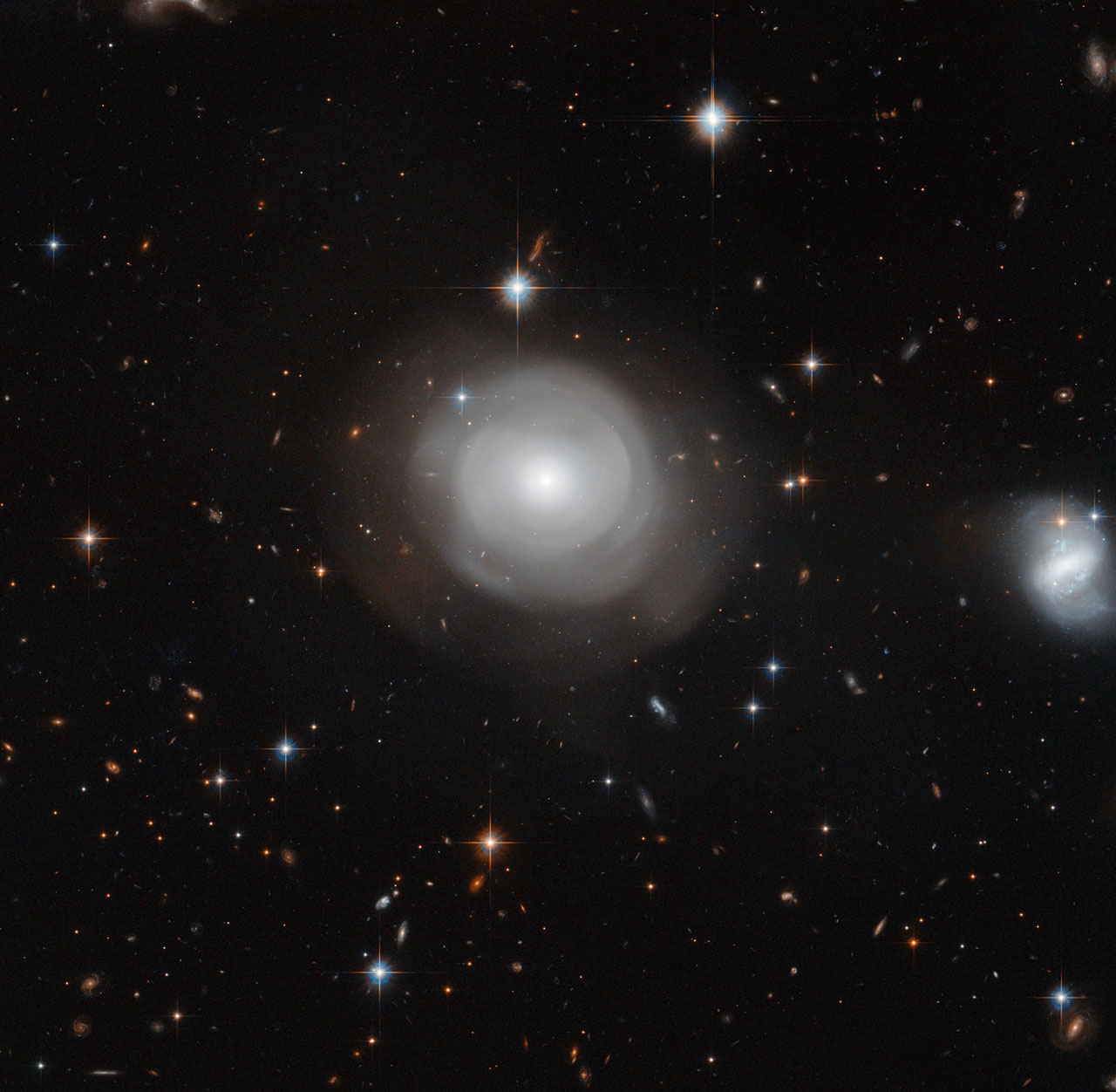

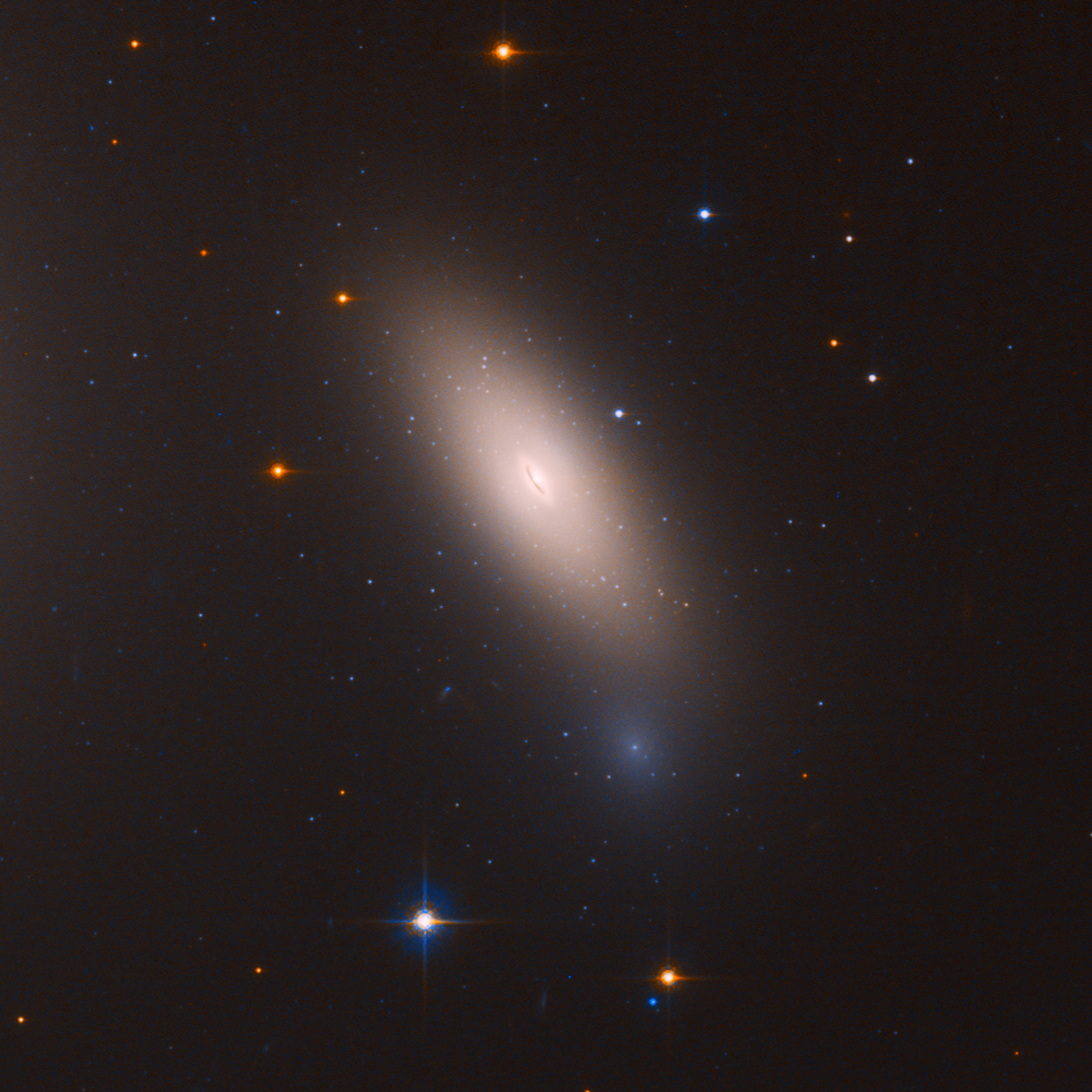

Against the void of space, galaxy ESO 381-12 seems to bloom. This galaxy, 270 million light-years from Earth, is in the constellation Centaurus. It's a lenticular galaxy, a hybrid between a spiral galaxy like the Milky Way and a stretched-out elliptical galaxy.

What make ESO 381-12 really strange, though, are the uneven, petal-like blooms that ghost outward from the main galactic body. Astronomers aren't entirely sure what causes these structures, or the clusters of stars that orbit on the galaxy's edges. It's possible that the blooms are shock waves from a relatively recent galactic collision that also provided the galaxy with new fuel for star formation.

Pretty Pinwheel

Messier 83 is a large, photogenic spiral galaxy with a bar-shaped center, similar to the Milky Way. It sits 15 million light-years away in the constellation Hydra. Messier 83 is weird in a couple ways. First, it appears to have a double nucleus at its center — perhaps the mark of two supermassive black holes holding the galaxy together, or perhaps the effect of a lopsided disk of stars orbiting a single, central black hole. Second, Messier 83 is a supernova supersite. Astronomers have directly observed six of these stellar explosions in the galaxy, along with remnants of 300 more. This puts Messier 83 in second place for supernovas, as only the galaxy NGC 6946 has produced more observable supernovas, with nine).

Cosmic Vermin

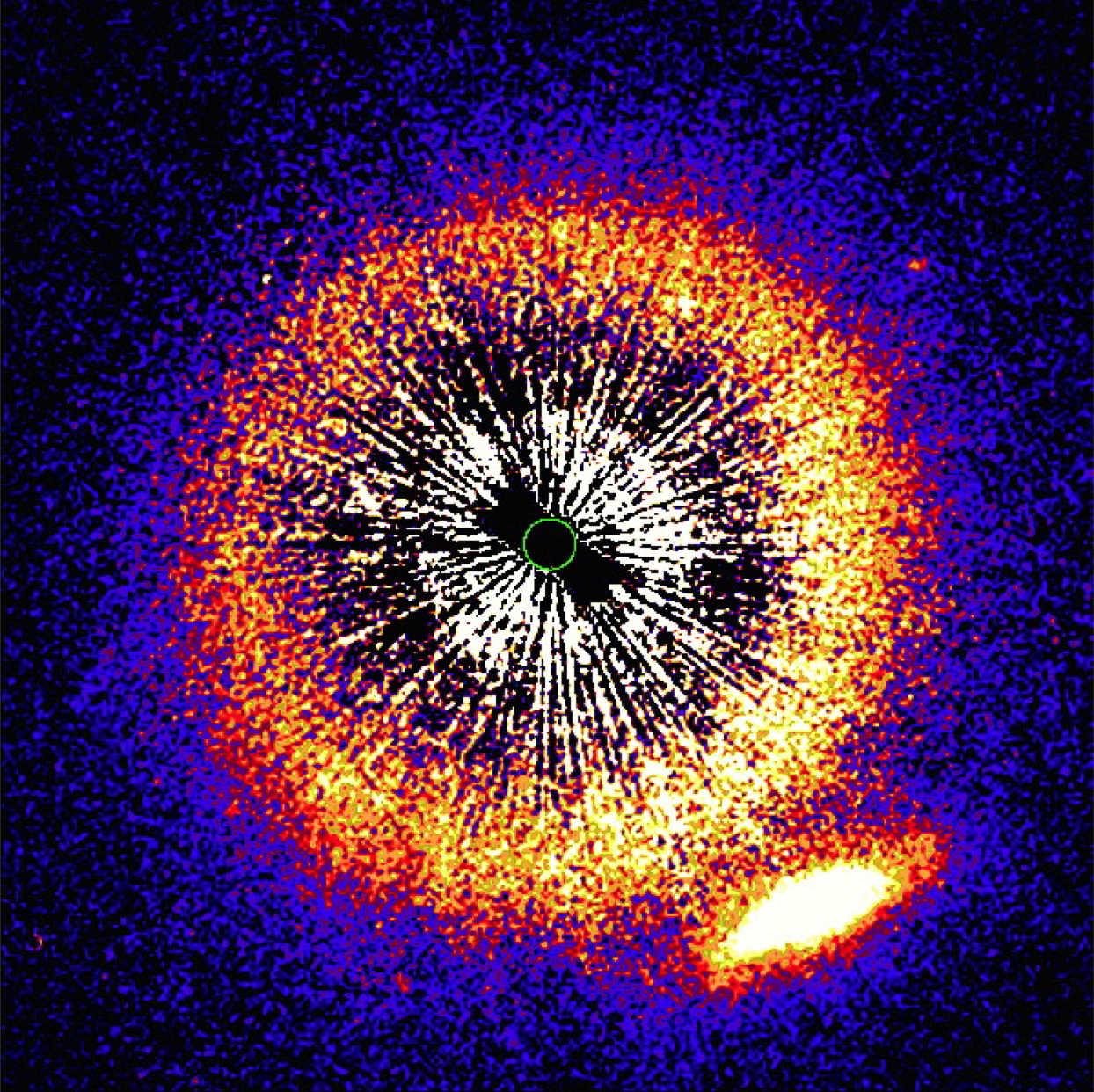

The image looks more like a psychedelic bit of dandelion puff than a cosmological phenomenon, but this snapshot captured by the Hubble Space Telescope has nothing to do with botany.

What you're seeing is a galaxy (the smudge at the lower right) beginning to pass behind a star (the dandelion-looking spiky sphere). The galaxy is nicknamed the Vermin galaxy" by some scientists because its light gets in the way of studying the closer star and its system. In 2020, the star will fully obscure the galaxy. Before then, scientists can study the spectra of light as the galaxy makes its transit behind the star, perhaps gleaning some information about the debris around the star from the light that makes its way through.

The Eye

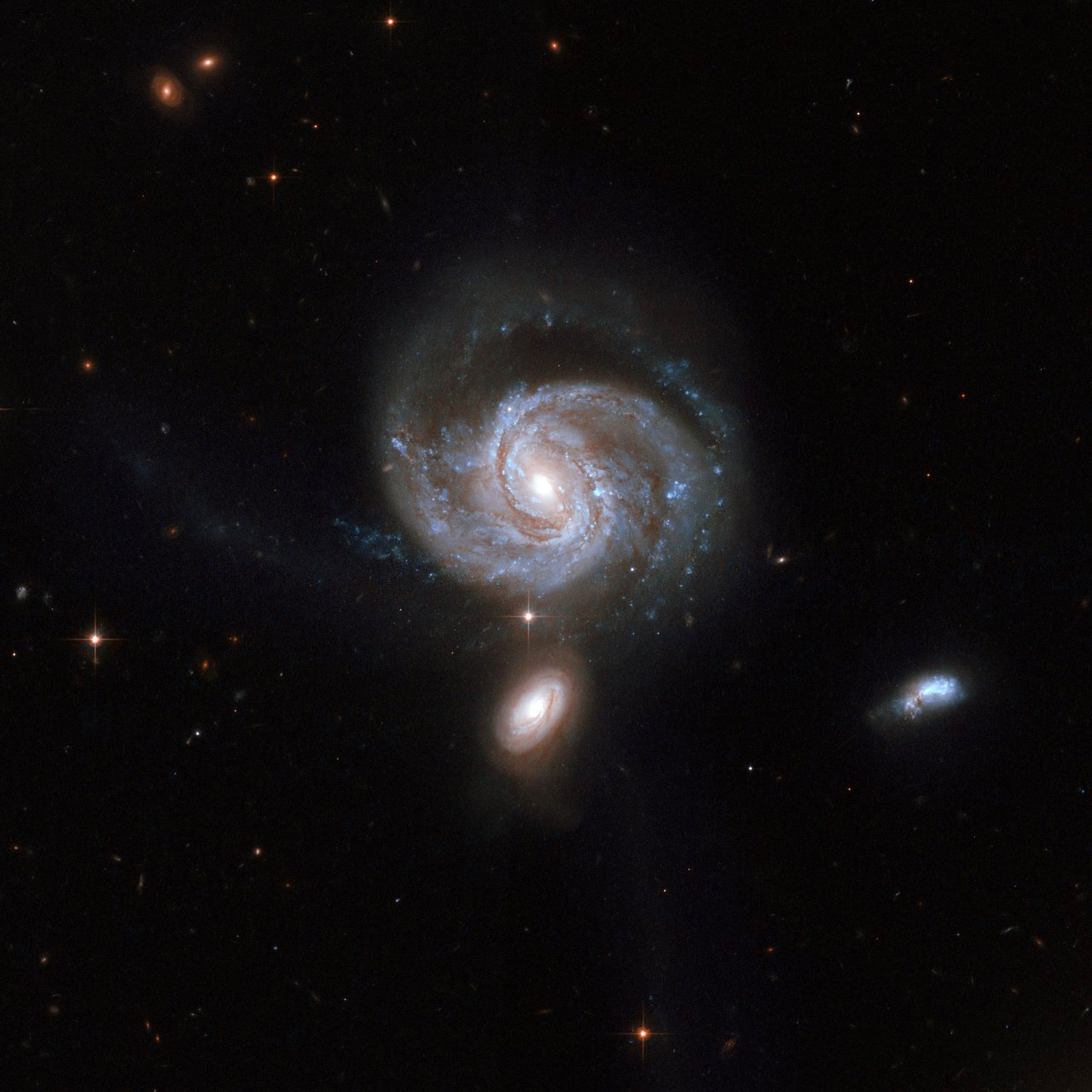

Ever feel like you're being watched? The disk of spiral galaxy IC 2163 seems to peer out into space with an enormous eye. This eye-shaped feature is actually a huge stream of stars and dust, produced when IC 2163 (at right in image) brushed against another spiral galaxy, NGC 2207 (left). These "ocular features" last only a few tens of millions of years, astronomer Michele Kaufman, who reported the discovery in 2016, said in a statement. That's a blink of an eye (pun intended) in the life span of a galaxy, so discovering one is a unique opportunity.

The researchers found that the gases of the eye feature race toward the center of IC 2163 at 62 miles per second (100 kilometers per second) before crashing like a wave on the shore, becoming more chaotic and slowing as they move toward the galaxy's center. The deceleration causes the gas to pile up and compress, which could set the stage for the formation of new stars.

Two hearts

Most galaxies are probably anchored by a supermassive black hole at their center. A few, though, contain not one, but two black holes.

One of these is NGC 7674, a spiral galaxy whose center boasts a pair of black holes a mere light-year apart. The galaxy (400 million miles from Earth) probably collected the spare black hole during a collision and merger with another galaxy. The only other galaxy known to have two black holes at its heart is a supermassive galaxy called 0402+379.

Arrested development

When you're a galaxy, you've got to consume other galaxies or die. Galaxy NGC 1277 chose the latter. This galaxy, first reported in 2018, is a mere 240 million light-years from Earth. It hasn't formed new stars for about 10 billion years, making it a dead galaxy.

Astronomers believe that NGC 1277 became stunted because it's moving too fast to gobble up other galaxies in its gravitational pull. (It's traveling through space at about 2 million mph, or 3.2 million km/h.) Without gas and dust from alien galaxies, NGC 1277 no longer forms stars. Some astronomers think that most galaxies started out looking at lot like NGC 1277, evolving spiral and other shapes only through later mergers with one another.

Coming our way

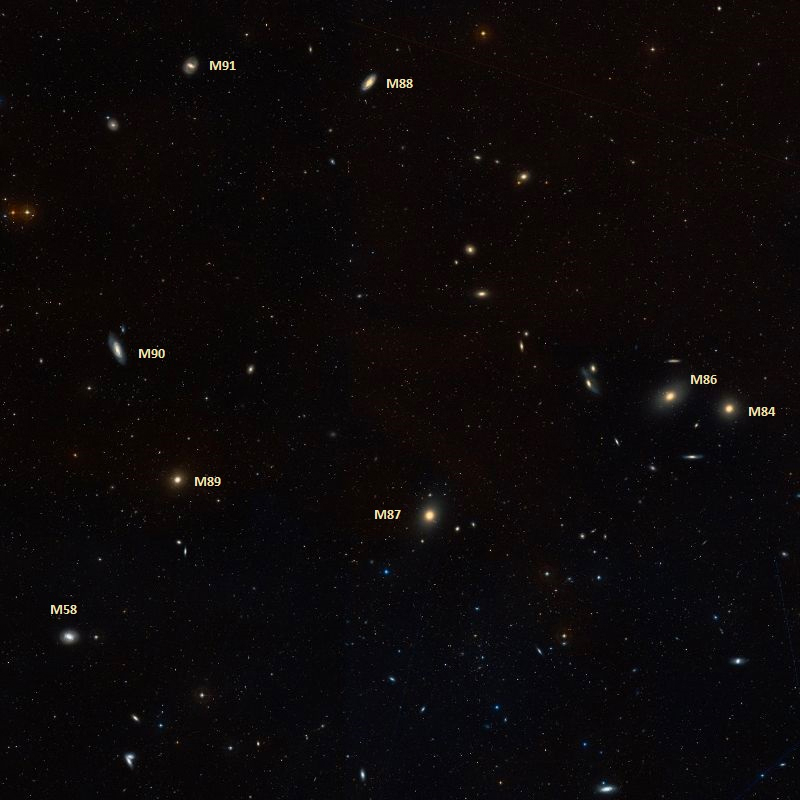

Most galaxies that scientists observe appear to be moving away from Earth, because space is still expanding. Not Messier 90, though. This spiral galaxy is about 60 million light-years away and moving toward the Milky Way.

Astronomers can detect this movement because the light coming from Messier 90 is skewed toward the blue end of the light spectrum. Objects moving away from Earth are redshifted, meaning their light emissions are weighted toward red. Messier 90 is part of a large group of galaxies called the Virgo Cluster. It can be seen from the Northern Hemisphere in May with a telescope or binoculars, sitting between the constellations Virgo and Leo, according to NASA.

Home, sweet home

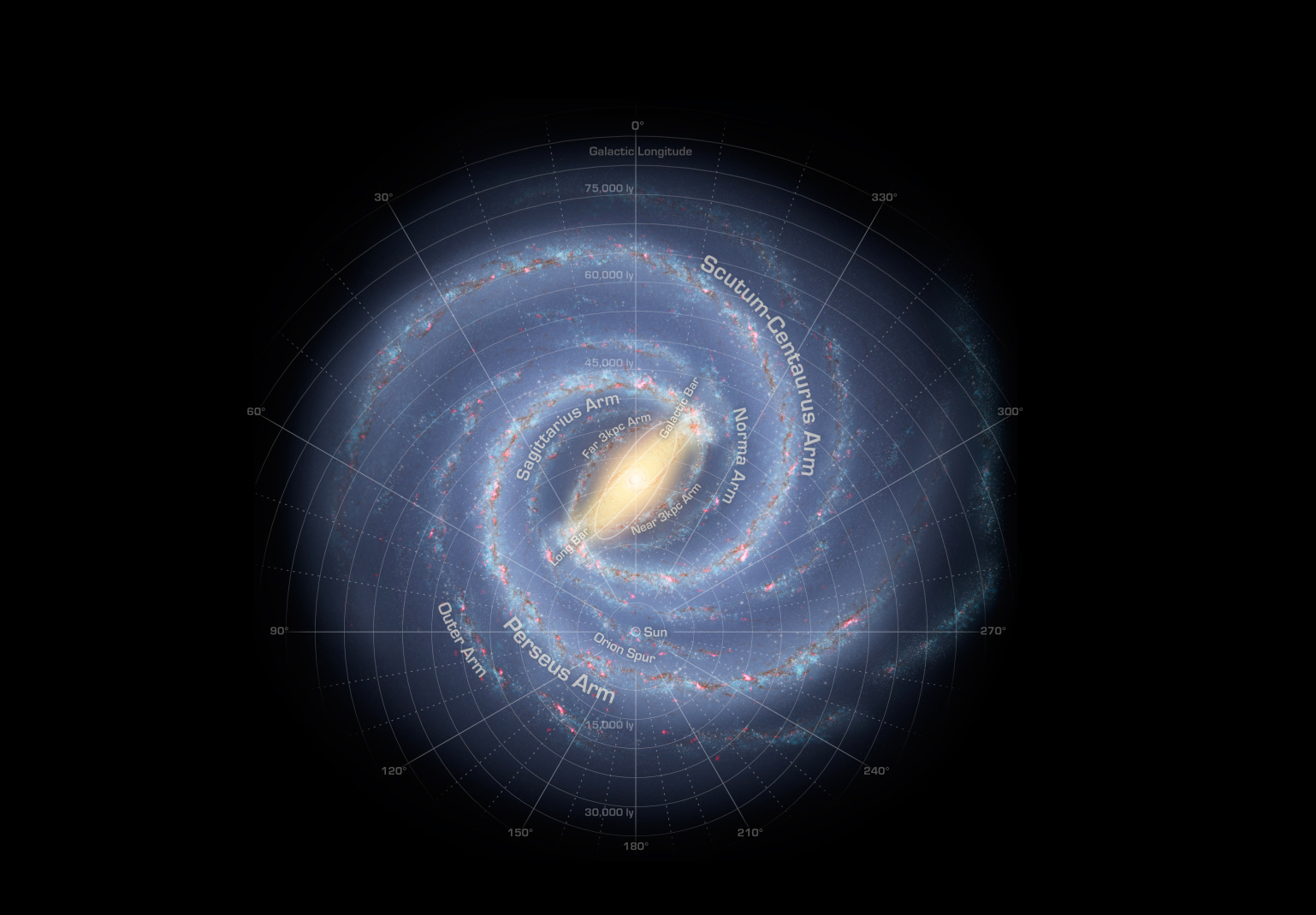

The Milky Way may be home, but that doesn't make it any less weird. It turns out that the Milky Way has been poaching galaxies from its neighbors.

In research published in October 2019, astronomers reported that four dwarf galaxies and two large galaxies (known as Corina and Fornax) used to orbit the Large Magellanic Cloud, a galaxy about 163,000 light-years away from our own. Now, all six of these galaxies belong to the Milky Way's orbit. As a bonus, the study also found that the Large Magellanic Cloud is stranger than previously believed. It hosts many tiny dwarf galaxies, some of which are so faint that they don't even have stars, only dark matter.

- 11 Fascinating Facts About Our Milky Way Galaxy

- Big Bang to Civilization: 10 Amazing Origin Events

- Spaced Out! 101 Astronomy Photos That Will Blow Your Mind

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.