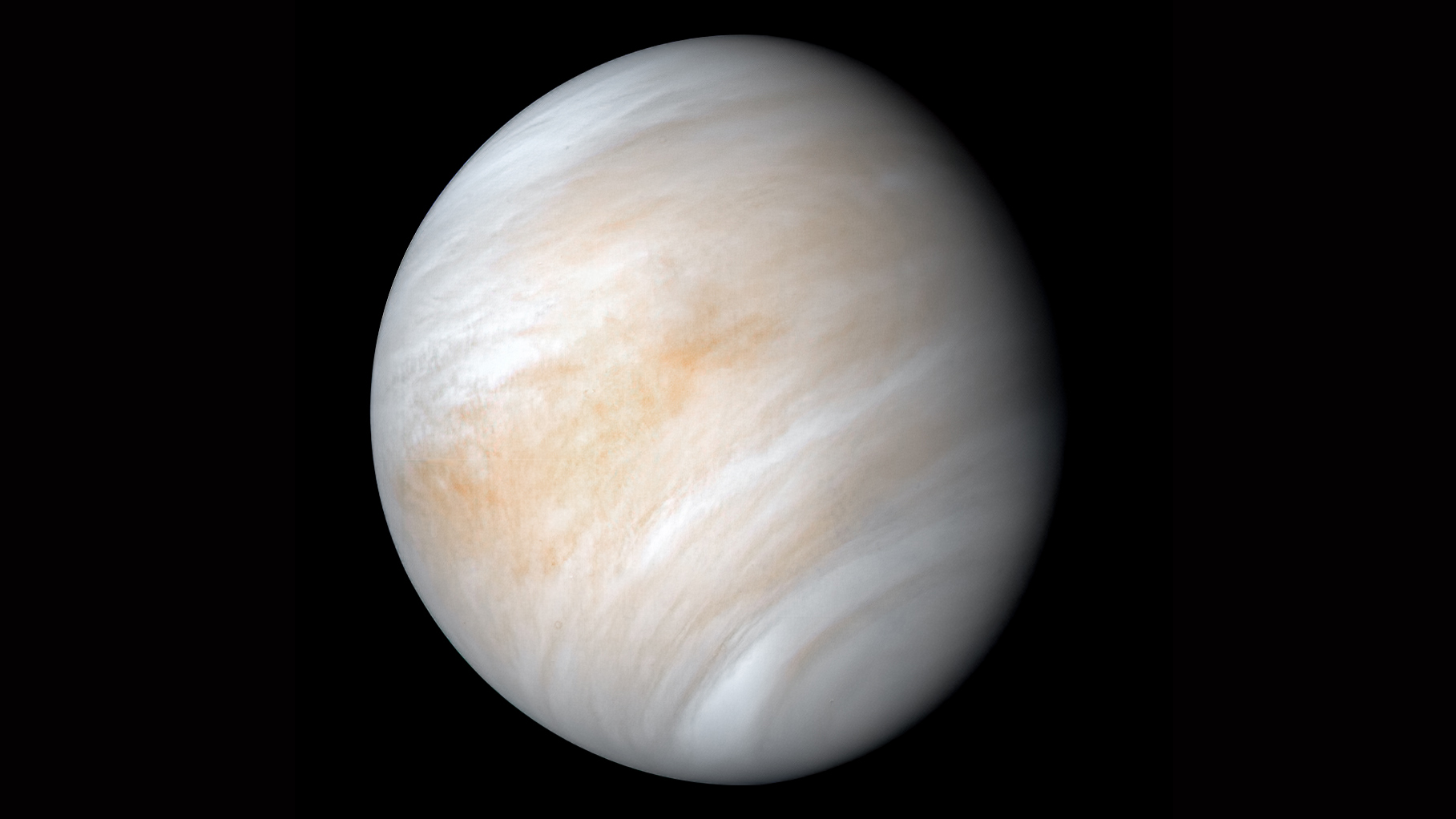

The clouds of Venus join the shortlist for potential signs of life in our solar system

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Venus isn't the only world beyond Earth where scientists have gotten a possible whiff of life.

Researchers announced today (Sept. 14) that they've spotted in Venus' air the fingerprint of phosphine, a stinky gas that here on Earth is produced only by microbes and humans, as far as we can tell.

The new find is not a detection of alien life. But it does suggest that something intriguing and mysterious may be occurring in Venus' clouds, an environment that astrobiologists have flagged as potentially habitable for microbial life.

Related: Strange chemical Venus clouds defies explanation. A sign of life?

More: 6 most likely places for alien life in the solar system

Intriguing and mysterious things are happening on other potentially life-supporting worlds as well. For example, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has rolled through several plumes of methane inside the Red Planet's Gale Crater and determined that background concentrations of the gas vary on a seasonal basis.

This is potentially exciting stuff, given that the vast majority of the methane in Earth's atmosphere is generated by living organisms. In addition, ultraviolet radiation from the sun breaks methane down in Mars' air within a few hundred years, so the stuff Curiosity is sniffing must have been emitted relatively recently.

But methane can be produced abiotically as well — for instance, by chemical reactions involving hot water and certain kinds of rock. And it's possible that the Gale Crater surges were caused by "burps" of methane that has been locked underground for millions or billions of years, scientists say. In short, Mars methane is far from a convincing biosignature at the moment; we don't know nearly enough to make such a monumental call.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There's also astrobiological action farther out in the solar system. Take the Saturn moon Enceladus, which harbors an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy shell. NASA's Cassini spacecraft identified complex organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — in the plume of water vapor wafting from Enceladus' south polar region.

Organics are not proof of life by themselves. The molecules are widespread throughout the solar system; they've been found in meteorites and in the tails of comets. But Enceladus' plume is generated by geysers blasting material from the moon's subsurface sea into space.

So, Cassini's observations show that potential chemical precursors to life — and perhaps even signs of life itself — are floating in this possibly habitable environment, which also likely features an energy source that organisms could tap into.

Cassini also spotted complex organics in the air of another Saturn satellite: Titan, the second-largest moon in the solar system. Scientists think Titan hosts two potentially life-supporting environments — a buried ocean of liquid water, and frigid surface seas of liquid methane and ethane. (If life does swim in Titan's hydrocarbon seas, it would be very different than that of Earth, which requires liquid water.)

These hints and clues may be building toward some very big discoveries in the not-too-distant future. NASA's recently launched Mars 2020 rover Perseverance, for example, will hunt for signs of ancient life after touching down inside the Red Planet's Jezero Crater in February 2021. Perseverance will also collect and cache several dozen samples that NASA and the European Space Agency will bring to Earth, possibly as early as 2031.

NASA is also developing a Titan mission called Dragonfly, which will land a rotorcraft on the big moon in 2034. Dragonfly will study Titan's complex chemistry, assess the moon's habitability and search for possible biosignatures, among other tasks.

We could see a Venus life hunt in the next few years as well. California-based company Rocket Lab aims to launch a private mission to Earth's hellishly hot sister planet in 2023. The plan involves dropping small, instrument-laden probes through the Venusian atmosphere to look for signs of life inthe planet's sulfuric-acid clouds.

So it's not crazy to think that we could soon get an answer to that biggest of queries: Are we alone?

"We're the first generation that could actually address this question, other than in a philosophical way," Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, told Space.com. "And that is special."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.