Supervolcano eruption on Pluto hints at hidden ocean beneath the surface

That ice lava had to come from somewhere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

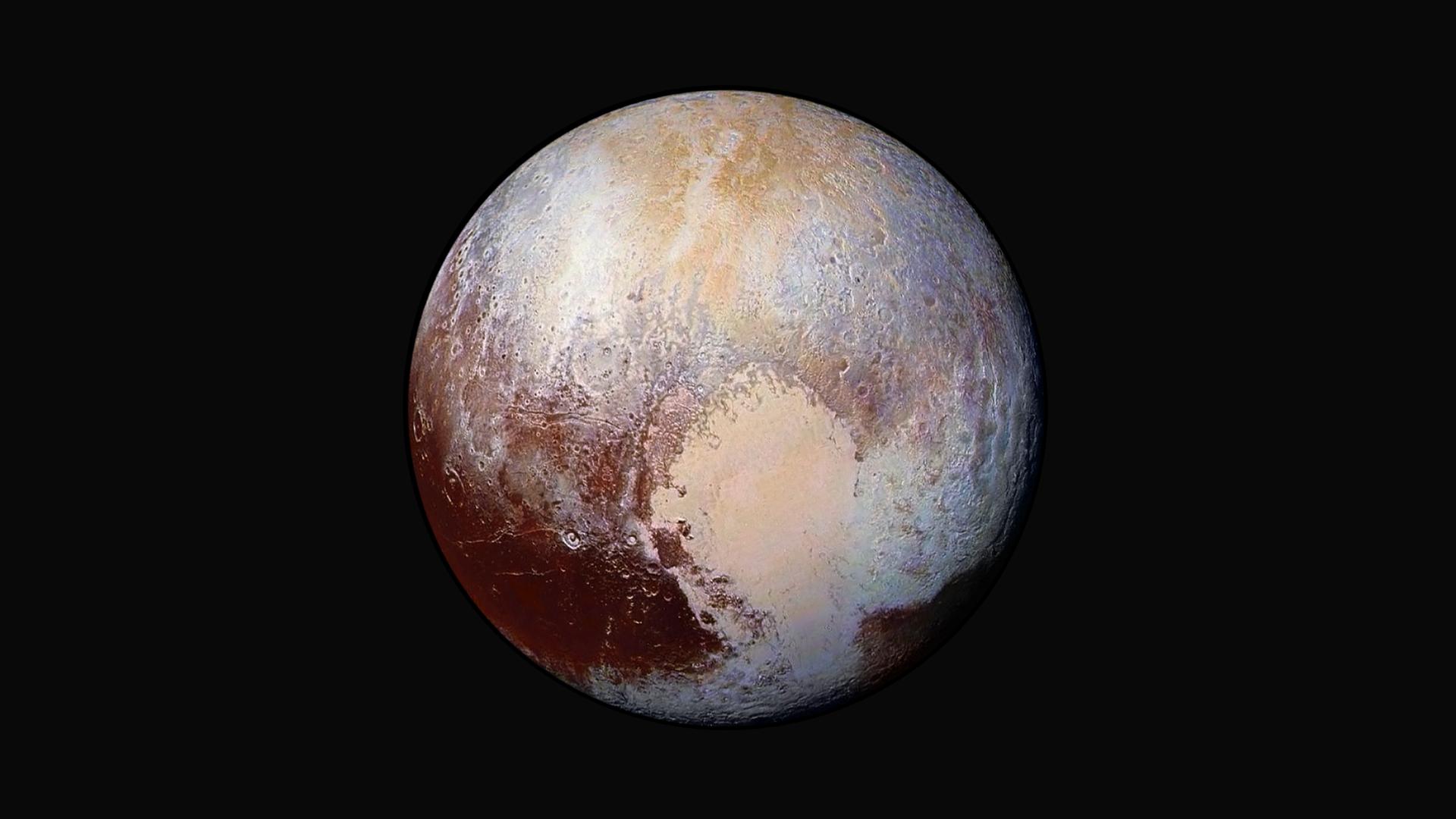

Although it has been close to a decade since NASA's New Horizons spacecraft visited Pluto, the dwarf planet continues to reveal itself as a surprisingly complex world.

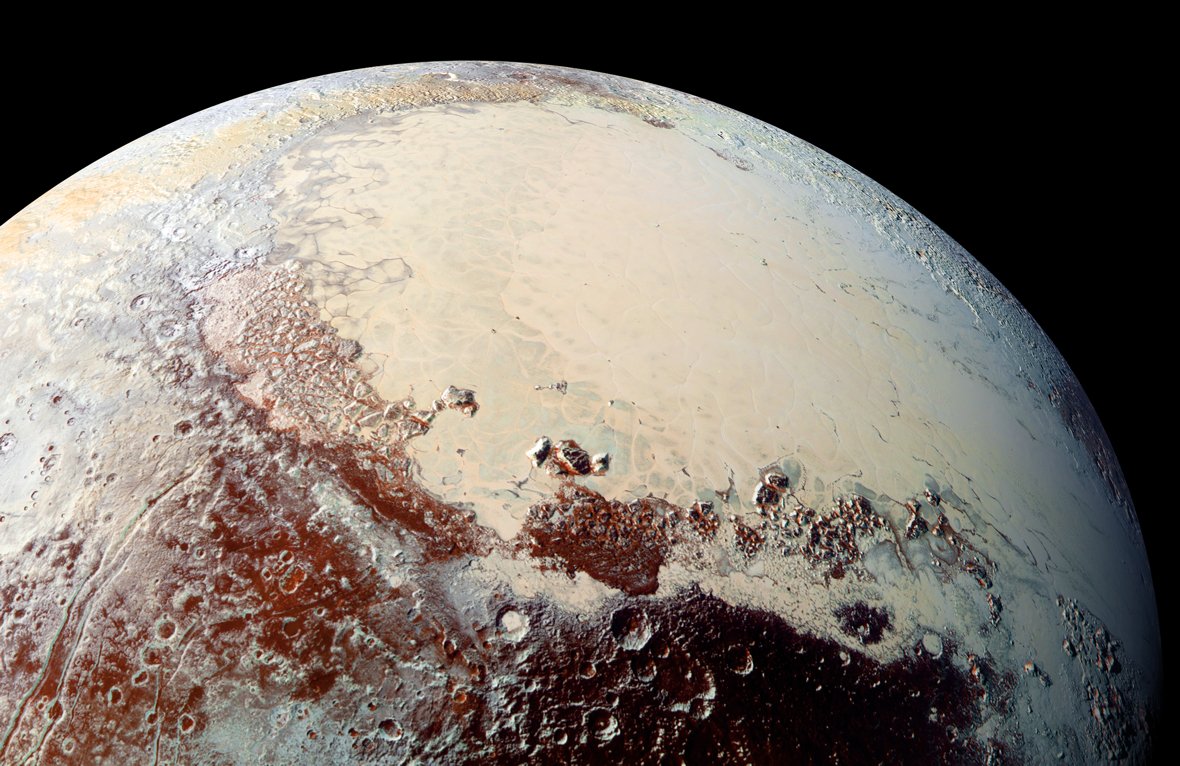

Scientists studying spacecraft data of an unusual crater near a bright, heart-shaped region on Pluto called Sputnik Planitia say they may have found a supervolcano that likely erupted just a few million years ago. That might sound like an incredibly long time ago, but cosmically speaking, it's pretty recent. For context, the solar system is more than 4.5 billion years old.

Instead of molten rock that blasts out of Earth's volcanoes, however, the 44-km-wide Kiladze crater appears to have spewed ice lava onto Pluto's surface in a process known as cryovolcanism. The process, which also unfolds on the moons of gas giants in our solar system and likely created other mystifying terrains on Pluto, is thought to have thrusted water from the world's hidden subsurface ocean onto its surface, reshaping it across millions of years.

Article continues belowVolcanoes require some sort of heat source to blow up, so the recent activity on Pluto suggests there is more heat remaining in the dwarf planet's interior than previously thought.

Related: Cracks on Pluto's moon Charon may be evidence of a frozen subsurface ocean

Researchers analyzed images New Horizons had clicked of the Kiladze crater, which resides northeast of Sputnik Planitia. While at first the crater looked similar to those left behind by meteorite impacts, it appeared to be missing a central peak otherwise expected for these geological phenomena. It also seemed slightly elongated, consistent with movements caused by tectonic forces from within Pluto, according to the new study, which is yet to be peer-reviewed.

Most of Pluto's surface is blanketed with methane and nitrogen ice, so the "tip-off that Kiladze is different" from rest of Pluto's surface is the strong presence of water ice around the crater, study lead author Dale Cruikshank, a professor at University of Central Florida, told Space.com. "The water ice stands out clearly from the methane ice that covers much of the planet's surface."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Pluto's axis is tilted at a sharp 120 degrees, which means it spins almost on its side, leading to dramatic changes in climate as it circles the sun. As a result, methane ice sublimates into a haze of hydrocarbons in the dwarf planet's atmosphere, some of which rain down as snow and coat its surface.

Over Pluto's 4.6 billion-year lifetime, scientists estimate this methane ice blanket must have gotten at least 14 meters (46 feet) thick. "Even a centimeter or two of this organic smog would mask the water ice spectral signature we observe," Cruikshank said.

Such a layer would have formed in just three million years. This led Cruikshank and his team to conclude Kiladze was "alive" only a few million years ago.

Scientists don't fully understand how cryovolcanic activity works on Pluto. The world is so small that it would have lost all heat from its formation long ago. One possibility is the dwarf planet contained radioactive elements in its core which released heat while decaying, although previous research suggested there just may not be enough of these elements to power-up Pluto.

Whatever the heat source might be, however, something appears to be keeping Pluto's subsurface ocean from freezing.

"As the planet cooled, it is plausible that pockets of liquid water were left behind, and perhaps our eruptions of water onto the surface tap into those pockets," Cruikshank said.

But, the researcher added: "We don't know."

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.