Lyrid meteor shower 2020 peaks this week! Here's what to expect.

Look up overnight on April 21 and April 22!

One of the "Old Faithful" of the annual meteor showers will be reaching its peak this week: the April Lyrids.

The 2020 Lyrid meteor shower this week coincides with the new moon, meaning that there will be absolutely no lunar interference with getting a good view of these celestial streakers. Lyrid meteors may be seen any night through April 25; they are above a quarter of their maximum in numbers for about 2.5 days of this time.

On their peak night, which occurs overnight on Tuesday (April 21) and into the early hours of Wednesday (April 22), as many as 10 to 20 meteors per hour may be visible under dark, clear skies. The peak usually lasts for just a few hours. In 2020, according to the Observer's Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, predicts this year's maximum occurring at 2 a.m. EDT (0600 GMT), which is considered to be good-to-excellent timing for observers across much of North America.

Of course, fewer meteors will be seen from locations hindered by bright lights or obstructions that block parts of the sky. In their book "Observe Meteors" published by the Astronomical League, authors David Levy and Stephen Edberg note of the Lyrids that, "... of the annual meteor showers, this is the first one that really commands attention, one for which you can organize a shower observing party with significant chance of success."

Related: Lyrid meteor shower 2020: When, where & how to see it

More: The most amazing Lyrid meteor shower photos of all time

Where to look and how to prepare

Look up this week! International Dark Sky Week 2020 is underway. Here's how to celebrate online.

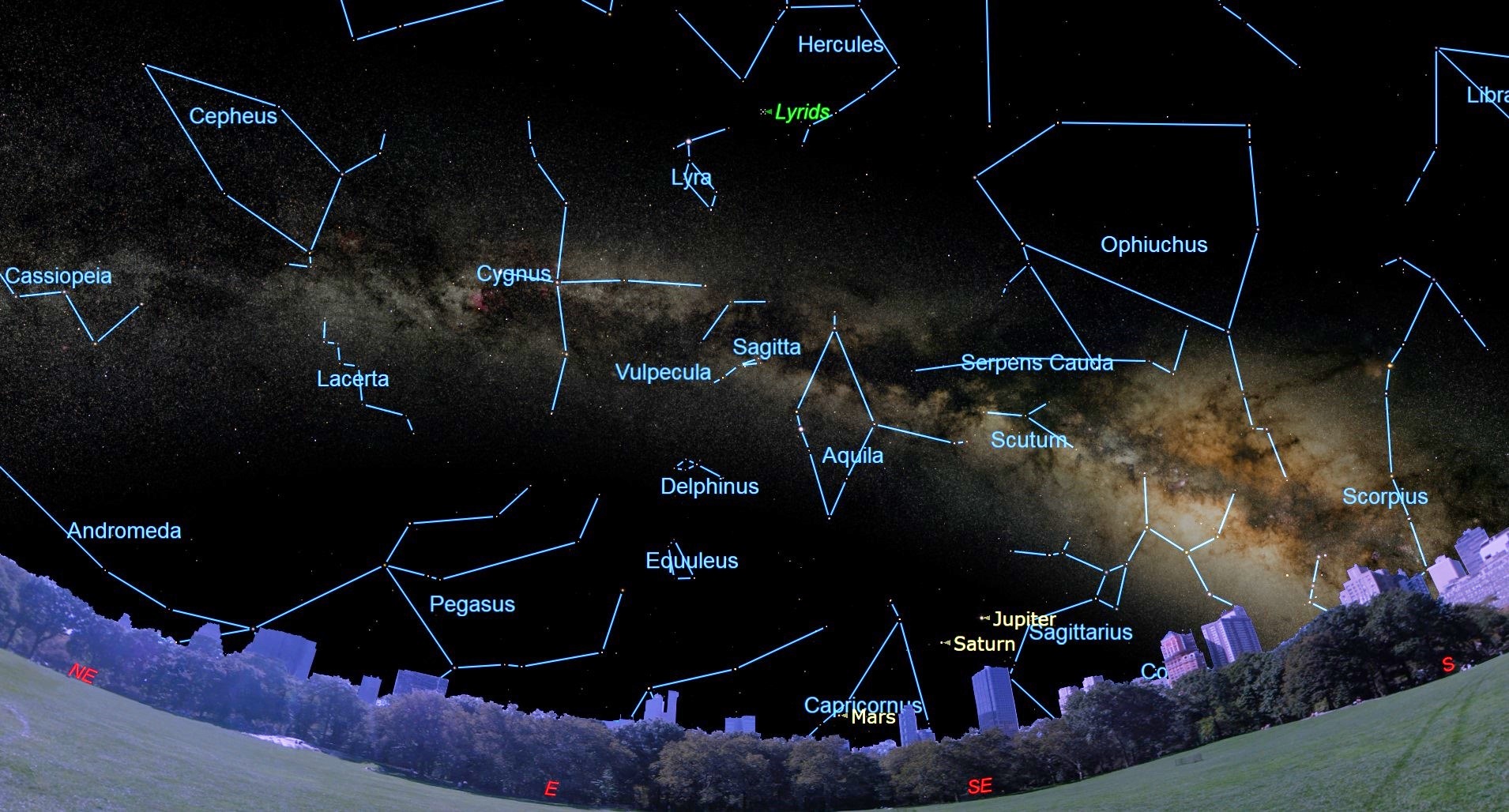

The paths of these meteors, if extended backward, seem to diverge from a spot in the sky about 7 degrees southwest (to the lower right) of the brilliant blue-white star Vega in the little constellation Lyra (hence the name "Lyrids"). Your clenched fist held at arm's length covers roughly 10 degrees of the sky. The radiant point is actually on the border between Lyra and the adjacent dim, sprawling constellation Hercules. Vega appears to rise from the northeast around 9 p.m. your local time, but by 4 a.m., it has climbed to a point in the sky nearly overhead. You might want to lie down on a long lounge chair where you can get a good view of the sky.

Bundle up too, for while it won't be a cold as on a midwinter's night, nights in April can still be quite chilly. In fact, the current national weather forecast is indicating predawn temperatures on Wednesday at or below freezing across the Northeast US and Great Lakes states, as well as parts of the northern and central Rockies.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Comet "garbage"

Send photos, videos, comments and your name and observing location to spacephotos@space.com for a potential story or gallery!

While seldom a rich display like the August Perseids or December Geminids, the April Lyrids have been described as "brilliant and fairly fast."

About 20 to 25 percent of them tend to leave a lingering incandescent trail behind it for a few moments. Their orbit strongly resembles that of Comet Thatcher which swung past us during the spring of 1861. There is no chance that anyone living today will see this comet when it returns to the inner solar system, as it isn't expected to swing by Earth again until the year 2276. However, the dusty material left behind by this "cosmic litterbug" along its orbit, produces an annual display of meteors in late April.

In the year 1867, Professor Edmond Weiss in Vienna noticed that the orbit of Comet Thatcher seemed to nearly coincide with the Earth around April 20 and later that same year, astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle confirmed the link between this comet and the Lyrids. Thus, the Lyrids are this comet's legacy: The meteors that we see from this display are the tiny particles that were shed by the comet on previous visits through the inner solar system.

Occasional flare-ups

There are a number of historic records of meteor displays believed to be Lyrids, notably in 687 B.C. and 15 B.C. in China, and in 1136 in Korea when "many stars flew from the northeast," according to one account.

On April 20, 1803, many townspeople in Richmond, Virginia were roused from bed by a fire alarm and were able to observe a very rich display between 1 and 3 o'clock. The meteors "seemed to fall from every point in the heavens, in such numbers as to resemble a shower of skyrockets."

In 1922, an unexpected Lyrid hourly rate of 96 was recorded and in 1982 several observers in Florida and Colorado noted rates of 90 to 100 on April 22 of that year. Lyrids give no clues as to when another such outburst might happen, hence the shower is always one to watch. Here's something to look forward to: Peter Jenniskens in his tome "Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets" predicts the next Lyrid outbursts might happen in 2040 and 2041.

Meanwhile, if your sky is clear early Wednesday before sunrise and if you’re in a sporting mood, why not head outside and try to catch a few “shooting stars?” Good luck!

Editor's note: If you snap a great photo Lyrid meteor shower that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and observing location to spacephotos@space.com.

- How to see the best meteor showers of 2020

- Infographic: How meteor showers work

- The 10 must-see skywatching events to look for in 2020

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.