Earth's atmosphere is full of microbes. Could they help us find life on other worlds?

If you're feeling lonely, take solace in remembering that there are countless tiny living things floating tens of thousands of feet above your head.

And as scientists have come to learn more and more about this high-flying life and how it interacts with Earth's surface, they are beginning to question just how implausible it is to wonder whether similar life could theoretically hide out in the clouds of Venus or still more exotic worlds.

"We humans really are bottom-dwellers underneath an ocean of atmosphere above our head, and we really don't know where Earth's biosphere boundary stops at extreme altitudes," David Smith, who studies life in the atmosphere at NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said at a roundtable event held on Dec. 14 at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, held virtually this month. "It seems just about anywhere we sample with NASA aircraft and balloons, we find signatures of microbial life."

Related: The top 10 views of Earth from space

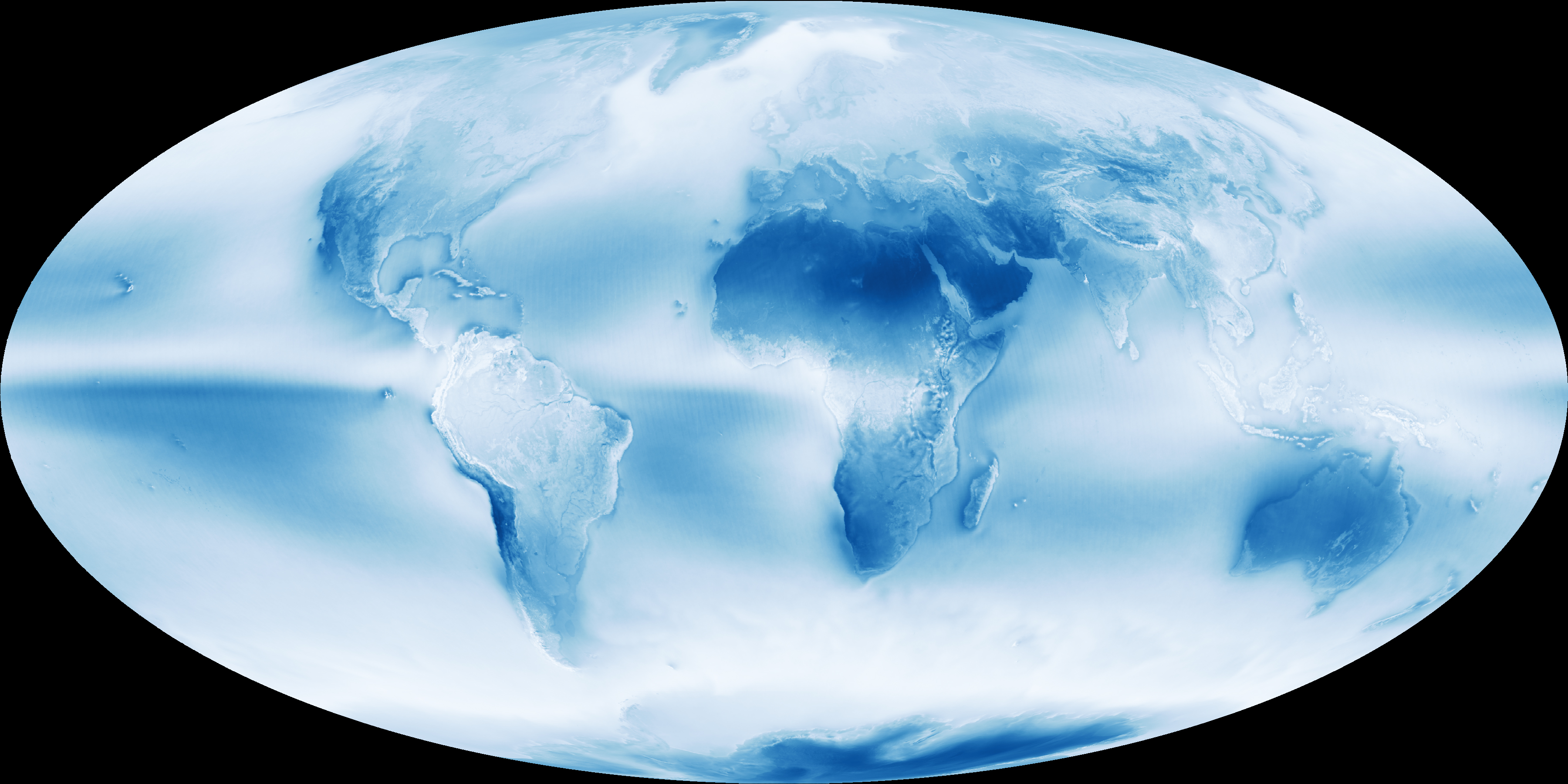

So far, life in Earth's atmosphere seems to be strictly microbial and a temporary affair, intimately connected to life on Earth's surface rather than an independent ecosystem. Tiny, hardy organisms are swept up from the thin transition where Earth's atmosphere meets the planet and carried into the lower layers of the atmosphere on an epic detour.

"Based on what we know, the things are just moving through the atmosphere," Kevin Dillon, a Ph.D. candidate in microbiology at Rutgers University, said during the panel. "Microbes travel and use the atmosphere almost like a highway, and specifically can hitch a ride in clouds."

Microbes end up in two layers of the atmosphere. In the lower troposphere, microbes mostly have to contend with the risk of drying out, Diana Gentry, a research scientist at Ames, said during the panel. Hence the appeal of clouds.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If you are picked up and suspended in the atmosphere, you're in danger of losing all of your water pretty quickly," Gentry said. "So clouds in the lower level are great — they're like these mobile water hotspots that can help keep you wet as you're picked up and transported around." In the troposphere, some microbes may survive pretty normally, even.

Meanwhile, life one level up, in the harsher stratosphere needs to contend with conditions that are still drier and even acidic. Here, microbes typically at least need to hunker down into a dormant state they can slip out of after returning to the surface. And of course, some die, and some are dead before they are swept up into the atmosphere.

So far, even in the best situation, atmospheric microbes don't seem to be doing much more intriguing than simply surviving, however. "We are really just beginning to understand the dynamics of how microorganisms from Earth's surface get swept up into the atmosphere, how long they stay aloft and whether or not they're doing anything meaningful in terms of activity or growth and reproduction aloft — we still don't know," Smith said. "We have a lot more work to do in Earth's atmosphere."

But just as the discovery of hydrothermal vent communities at hot seams in the ocean floor prompted astrobiological dreams of life deep inside the hidden oceans of icy moons, so scientists now wonder whether the strange extremity of atmospheric life on Earth could be a template for determining whether anything is alive elsewhere in this chain of rocky worlds we call the solar system.

Life in the solar system

Of course, for as many uncertainties as there are when it comes to life in Earth's atmosphere, they only multiply in atmospheres beyond Earth's.

One key constraint is that while we know full well Earth's surface is a paradise from which microbes can take their grand adventure, other planetary surfaces in the solar system are either certainly or likely more hostile to life as we know it, although they may well have been plenty habitable in the distant past. The appeal of someplace like Venus, for example, as a destination in the search for life is in its atmosphere, where some scientists have argued that liquid droplets about 30 to 37 miles (48 to 60 kilometers) up could act as a haven in the acidic, hot environment for which Venus is famous.

That harshness means that on worlds like Venus, life would need to remain in the atmosphere permanently, rather than visiting as it does on Earth. And that permanence means those holes scientists have about whether microbes can, say, reproduce while aloft, would need filling.

And gravity would consistently steal some hypothetical microbes out of the one cozy layer, Gentry noted. "A challenge to life that is unique to life in the atmosphere is that because you're floating, you're constantly losing some of your life that is up there, just to gravitational settling over time," she said. "In order for life to be able to persist long-term in an atmosphere, it has to be able to reproduce fast enough to make up for those losses."

Then there's that water issue. Earth's clouds are special: They are the only modern atmospheric clouds in the solar system built primarily of water vapor, making them uniquely promising for life human scientists are most attuned to recognize. Venus' clouds? Sulfuric acid. Mars has some carbon dioxide wisps. Neptune's moon Triton boasts nitrogen clouds. All of them are intriguing, but no water is a real hurdle.

"One of the major themes in astrobiology tends to be 'follow the water' because, for Earth-like life as we know it, water is a requirement," Gentry said. "Because those are not water-based clouds, they're not interesting for the same reason that water-based clouds are interesting."

And beyond

Just as Earth serves as a template for considering other solar system worlds, our neighborhood offers archetypes to consider for worlds beyond our star — with another step down in how much we know about them, of course. Where Earth is our daily backdrop and the planets are destinations for sophisticated spacecraft, exoplanets are mostly blemishes silhouetted against their stars in astronomical observations.

And it turns out, spotting atmospheric life is tricky, even here on Earth. "Every time we fly through clouds and make cloud water collections, we have this really strong signal of Earth life. And yet, we can't measure it remotely," Smith said. "We know life is in those clouds, but we don't have any instruments that are sensitive enough to detect that without actually collecting the cloud water."

So don't expect scientists to make any announcements about atmospheric life on other worlds any time soon.

"It is extraordinarily difficult to prove or to see whether an exoplanet is a living world," Noam Izenberg, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, said.

But don't stop wondering about it either, he said.

"If there's a chance for life on Venus, then yes, there's probably chances for life on Venus-like worlds elsewhere," Izenberg said. "If there's life on Earth, yes, there's probably a chance for life on Earth-like worlds elsewhere."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.