Astroscale's space junk removal satellite aces 1st orbital test

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

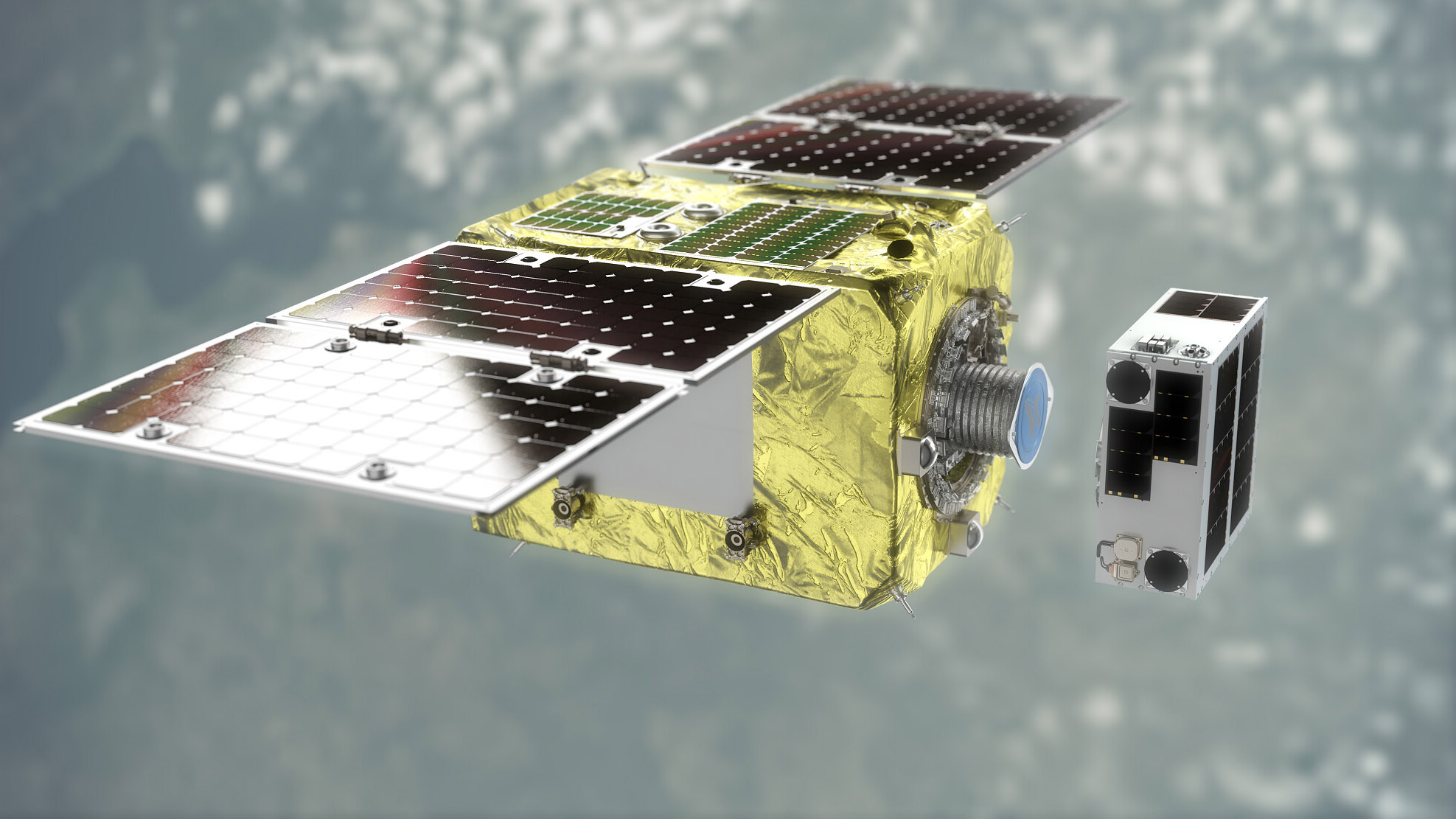

The ELSA-d spacecraft of Japan-based startup Astroscale has successfully captured a simulated piece of space junk, completing the first phase of a demonstration mission that could pave the way for a less cluttered future in orbit.

Launched on March 22, ELSA-d (short for "End-of-Life Services by Astroscale demonstration") brought with it to orbit a 37-pound (17 kilograms) cubesat fitted with a magnetic docking plate. During the experiment on Wednesday (Aug. 25), ground controllers first remotely released a mechanical locking mechanism attaching the cubesat to the main 386-pound (175 kg) removal craft, Astroscale said in a statement. The two satellites were still held together by the magnetic system, which is responsible for capturing the debris.

The cubesat was then released completely and recaptured before floating too far away from the main spacecraft. Astroscale said on Twitter that this maneuver was repeated several times. This short demonstration enabled Astroscale to test and calibrate rendezvous sensors, which enable safe approach and capture of floating objects.

Related: Watch a Satellite Fire a Harpoon in Space in Wild Debris-Catching Test (Video)

"This has been a fantastic first step in validating all the key technologies for rendezvous and proximity operations and capture in space," Astroscale founder and CEO Nobu Okada said in the statement. "We are proud to have proven our magnetic capture capabilities and excited to drive on-orbit servicing forward with ELSA-d."

The operation was managed from Astroscale's ground control center in Harwell, U.K. In an earlier statement, the company explained the challenges of the demonstration, the first orbital capture experiment performed by a commercial company.

The ground control team had to rely on 16 ground stations located in 12 countries around the world to maintain constant contact with the spacecraft for up to 30 minutes at a time, Astroscale said in the statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"A typical low Earth orbit mission's connectivity ranges from 5-15 minutes, with 1 or 2 ground station providers in a couple of locations," Alberto Fernandez, Astroscale's head of ground systems engineering, said in the statement. "ELSA-d is performing complex demonstrations that have never been done before, and we need a very reliable and unusually long chain of connectivity to provide a constant real-time data feed throughout the demonstrations."

ELSA-d will conduct additional, more ambitious tests in the next few months, Astroscale said. These tests will see the small satellite drift farther away from the removal craft. First, the cubesat will move away but remain in a stable position. Next, the ground controllers will make it tumble, just like an uncontrolled piece of space junk would in space. The latter experiment will allow Astroscale to simulate a realistic scenario in which the removal spacecraft would first have to inspect its target, analyze its motion and then approach it in the safest and most efficient way.

Earlier this year, the company signed a £2.5 million deal (about $3.4 million US) with internet megaconstellation operator OneWeb to develop a commercial system for removing defunct satellites from orbit. The technology, called ELSA-M ("End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-Multi"), will enable removing multiple satellites one by one with a single deorbiting spacecraft. Astroscale is also cooperating with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) on a mission that will inspect a spent Japanese rocket stage in 2023.

Since the launch of the first-ever satellite, the Soviet Union's Sputnik 1 in 1957, humankind has placed into orbit over 11,000 satellites, according to a database maintained by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. The number has been rising sharply in recent years due to the advent of cheaper smaller satellites and especially megaconstellations, such as SpaceX's Starlink.

There are currently more than 7,000 satellites in orbit, but only about 3,400 of them are active. The rest are old defunct spacecraft that are frequently too high above Earth to be pulled down by its gravity and burn up in the atmosphere.

There are also countless pieces of space debris — fragments created by collisions and explosions. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that approximately 34,000 space debris pieces larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters) currently orbit Earth. The number of fragments between 0.4 and 4 inches (1 to 10 cm) is believed to be around 900,000. In addition to that, there could be a staggering 128 million objects between 0.04 and 0.4 inches (1 millimeter to 1 cm) in size.

Experts believe that removing satellites after their mission ends is key for maintaining a safe orbital environment. In the late 1970s, NASA physicist Donald Kessler predicted that objects in space will at some point start colliding in an out-of-control way, each collision generating fragments that cause further and further collisions. Some experts believe that this collision cascade, also known as the Kessler Syndrome, is already happening.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.