Astro Restoration Project pieces together space shuttle astronomy payload

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In the same year the Hubble Space Telescope was deployed, NASA launched the first of two space shuttle missions dedicated to the study of astronomy and astrophysics. Now, three decades later, the hardware that made up the Astro-1 mission (and its 1995 follow-up, Astro-2) is being recovered, reunited and restored for museum display.

The Astro Restoration Project, a volunteer-run effort supported by commercial sponsors, the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama and the Smithsonian, is now well underway towards its goal of bringing the STS-35 (and STS-67) mission hardware back to its as-flown condition. Many of the people working on the project are retired NASA employees who configured the payload for its launch.

"In 1985, preparing for Astro-1, I was the one who originally installed those boxes," Mike Haddad, a former NASA mechanical engineer and member of the restoration project, said in a NASA interview. Haddad was referring to remote acquisition units — the equipment used to send signals from the Astro hardware to the shuttle and then down to Earth.

"Doing the same procedure 35 years later? It was like coming home," he said.

Piecing it together

Held in the shuttle's payload bay by two Spacelab pallets that were developed by the European Space Agency (ESA), the Astro payload included three ultraviolet telescopes mounted to an aluminum frame. The assembly was then mounted to a three-axis gimbaled platform, called the Spacelab Instrument Pointing System, which provided the accuracy and stability needed to image astronomical objects.

The Astro Restoration Project has been able to recover 90% of the original hardware.

The three ultraviolet telescopes were sent back to their principal investigators at Johns Hopkins University, University of Wisconsin-Madison and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. The pointing system was claimed by the Smithsonian as part of the collection held by the National Air and Space Museum.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Typically, when flight hardware is returned to Earth, NASA refits or refurbishes it for other missions, or strips and cannibalizes components for other uses," Haddad said.

In the case of unique or "mission peculiar" pieces, a lot of it is auctioned off through government surplus sales. Such was the fate of the fourth telescope to fly on Astro-1, the Broad-Band X-Ray Telescope (BBXRT), which as recent as five years ago, was listed for sale on eBay by its owner. (The BBXRT, which only flew once, was mounted on a separate pointing system secured to its own structure in the shuttle's payload bay.)

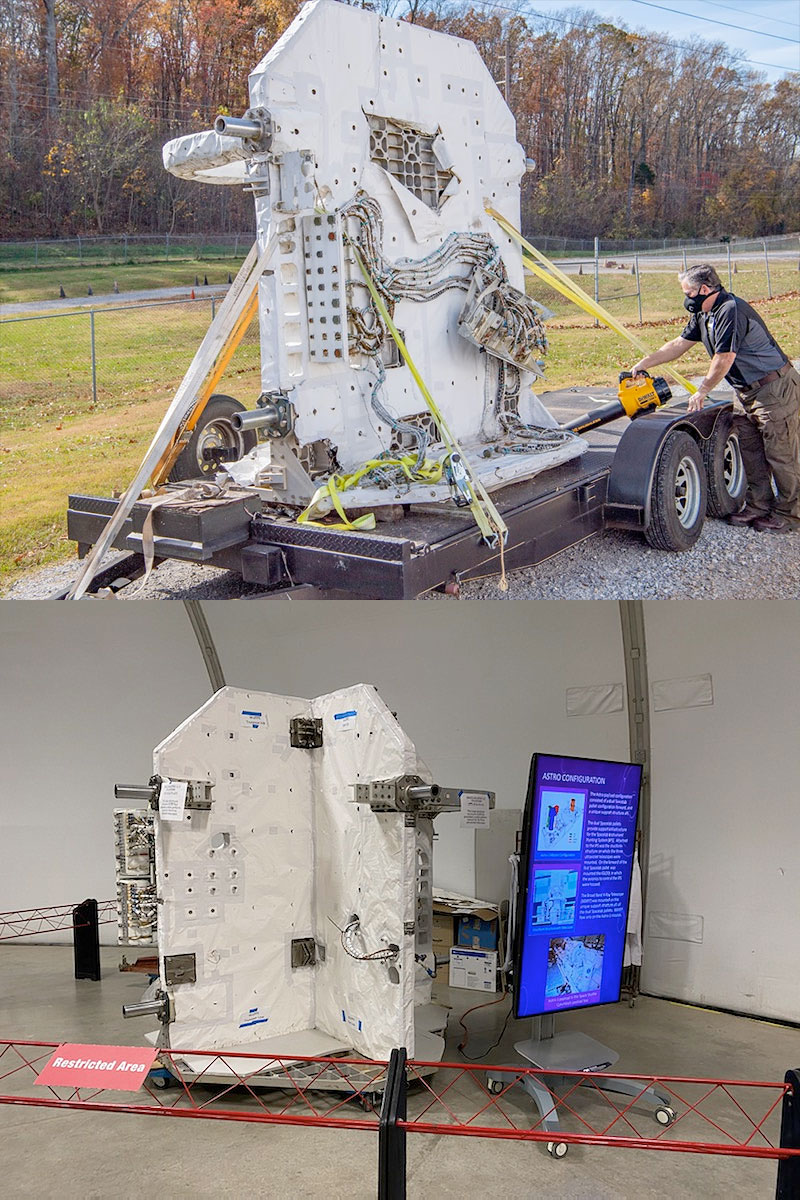

The 8-foot-by-8-foot (2.4-by-2.4-m), 3,000-pound (1,360-kg) aluminum frame, or cruciform, was found by happenstance in a North Alabama auction yard. Similarly, the optical sensor package that helped fix the telescopes on the same observation point in space was discovered in a scrapyard in Titusville, Florida.

"It was still in its original shipping box," said Scott Vangen, the restoration project's lead and an alternate payload specialist for the Astro-2 mission.

Phased approach

Although recovered, the cruciform was in poor shape. Using a work area provided by the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, dozens of civil service and contractor volunteers worked at stripping off rotted insulation blankets, gently cleaning parts with toothbrushes and pressure-washing others.

The team also received help in manufacturing replacement brackets and other small elements from the students in NASA's HUNCH (High schools United with NASA to Create Hardware) program, which teaches practical hardware design and fabrication techniques at more than 200 schools nationwide.

Also aiding in the restoration was a mission procedures log, which was sourced from the estate of former Astro engineer. The log identified hundreds of detailed drawings and schematics that broke down every component, which were then able to be found, scanned and provided to the project team by Marshall Space Flight Center archivists.

"Preserving the hardware is somewhat academic if you don't have the documentation," Vangen said. "We needed the original drawings to put the pieces back together again."

After a four-month effort, "phase one" of the restoration project was completed and the restored cruciform went on display at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in April.

The next phase will be to reinstall the restored optical sensor package and the first of the three telescopes, the Wisconsin Ultraviolet Photo Polarimeter Experiment, which are slated to be reunited with the cruciform this fall. They will then be joined by the remaining two ultraviolet telescopes to complete the display.

The restored Astro cruciform will be displayed by the U.S. Space & Rocket Center through at least 2023, until the Smithsonian is ready to exhibit it with its Spacelab components — including the pointing system and pallets — at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia.

"Free-flying payloads and deployables such as Hubble rewrote the science books, but they'll never come back to Earth, never stand on display as examples of what we can achieve," said Vangen. "With Astro, our grandchildren and great-grandchildren will be able to touch hardware that flew to space and into the history books."

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2021 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.