Former CEO of Google spearheads 4 next-gen telescopes — 3 on Earth and 1 in space

"We're going to do it in three years, and we're going to do it for a ridiculously low price."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

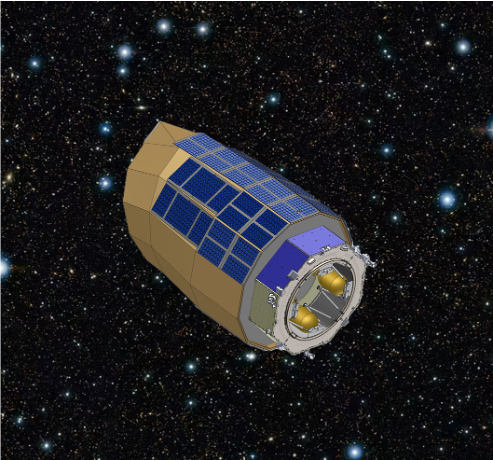

PHOENIX, Arizona — On Wednesday (Jan. 7), scientists made a major announcement at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society: Four next-gen telescopes have secured private funding, and they should roll out at a very rapid pace. Three are ground-based scope arrays and one is a space observatory named Lazuli that would have 70% more collecting area than the Hubble Space Telescope. If all goes to plan, Lazuli could launch as soon as 2029.

"We're going to do it in three years, and we're going to do it for a ridiculously low price," Pete Klupar, executive director of the Lazuli project, said during the conference.

The announcement comes from Schmidt Sciences, a philanthropic organization forged by Wendy Schmidt and Eric Schmidt, the latter of whom was CEO of Google from 2001 to 2011. It's notable for a philanthropic organization to be the driving force behind so many big astronomy projects — with specific costs yet to be revealed — for a couple of reasons. For one, the Trump administration has become notorious over the last year for undermining science in different ways, like slashing science organization budgets (including NASA's, though Congress is fighting those cuts) and laying scientists off in hefty swaths at a time.

"Between the congestion of space and the tightening of government budgets, a storm of possibilities is formed," Klupar said. "If we stick to traditional timelines, we lose generations of data. On the other hand, we can't be slapdash. We must move forward, but we must not compromise on our mission success."

If everything works out, Lazuli will become the first privately funded space telescope in history. This is a big deal because, while we've seen commercial interests clearly permeate the space sector over the last several years, they haven't so much aligned with what some may call "science for science's sake" these days — at least not as strongly as the Schmidt Observatory System appears to.

Jeff Bezos' aerospace company Blue Origin, for instance, has been taking paying customers to the edge of space since 2021, and Elon Musk's SpaceX still has its eye on landing humans on Mars. The first private lunar lander made a touchdown on the moon just last year, and even climate-focused companies have sent private satellites to space in order to monitor our planet's health. But a powerful space telescope being funded without government assistance still seems like a shift.

"One of the reasons why we're better is because we have one shareholder. This eliminates analysis paralysis," Klupar said. "We've proven this model works in commercial spaceflight. It's been proven in the small [satellite] revolution. Now we're investigating how to apply those lessons to large-aperture astronomy."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To get into some specifics with Lazuli: The telescope will have a 3.1-meter-wide (10.2 feet) mirror, meaning it should capture 70% more light than the iconic Hubble Space Telescope. It is expected to provide quick observations across both near-infrared and optical wavelength bands, and will be placed into a lunar-resonant orbit, a known cost-effective and stable orbit option.

The telescope will have three instruments: a wide-field optical imager, an integral field spectrograph and a high-contrast coronagraph. Scientists are especially excited about the coronagraph, because this instrument can be used to directly image exoplanets.

"There's a lot of technology that we're going to demonstrate on Lazuli that will complement what [NASA's upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope] is doing and help us find the path most quickly and efficiently to get to Earth-like planets around sun-like stars," Ewan Douglas of the University of Arizona said during the conference.

The other two instruments are really cool as well; they can both be used to dissect secrets of the cosmos, like the mystery of the universe's expansion rate (popularly called the Hubble Tension) and help with supernova modeling.

The three ground-based telescope projects that will be part of the Schmidt Observatory System include the Argus Array, the Deep Synoptic Array (DSA) and the Large Fiber Array Spectroscopic Telescope (LFAST).

The Argus Array, slated to be operational as early as 2028, will survey the sky in visible light with 1,200 small-aperture telescopes that work together to offer a combined collecting area equivalent to an 8-meter-class telescope. According to a description on the Schmidt Sciences website, Argus will offer an "instantaneous field of view of 8,000 square degrees" while scanning the sky and enable "exploration of the transient universe on approximately second-long timescales."

"When a multi-messenger event is detected, optical surveys have to slew to that position and start tiling over the uncertainty region. Argus takes a different approach with an overwhelmingly large field of view that eliminates the need to tile," Nicholas Law of the University of North Carolina said during the conference. (A “tile” in this case refers to one section of the sky covered by a detector. “Tiling” means combining different tiles to increase the accuracy of measurements.)

"In our fastest operation mode, we can take images as fast as once per second,” Law said.

The Deep Synoptic Array, meanwhile, will be built in Nevada and consist of 1,656 1.5-meter aperture telescopes and span an area of 20 kilometers by 16 kilometers (12.4 by 9.9 miles). Its specialty will be scanning the sky in radio bands, which can reveal radio sources like galaxy centers or black holes otherwise obscured by things like interstellar dust that can make them hard to detect in other wavelengths. It's expected to be operational by 2029.

"The DSA is unprecedented. It's an order of magnitude more service speed than any telescope, current or planned," Gregg Hallinan of the California Institute of Technology said during the conference. "To put it in context, every radio telescope ever built has detected about 10 million radio sources. We'll double that in the first 24 hours."

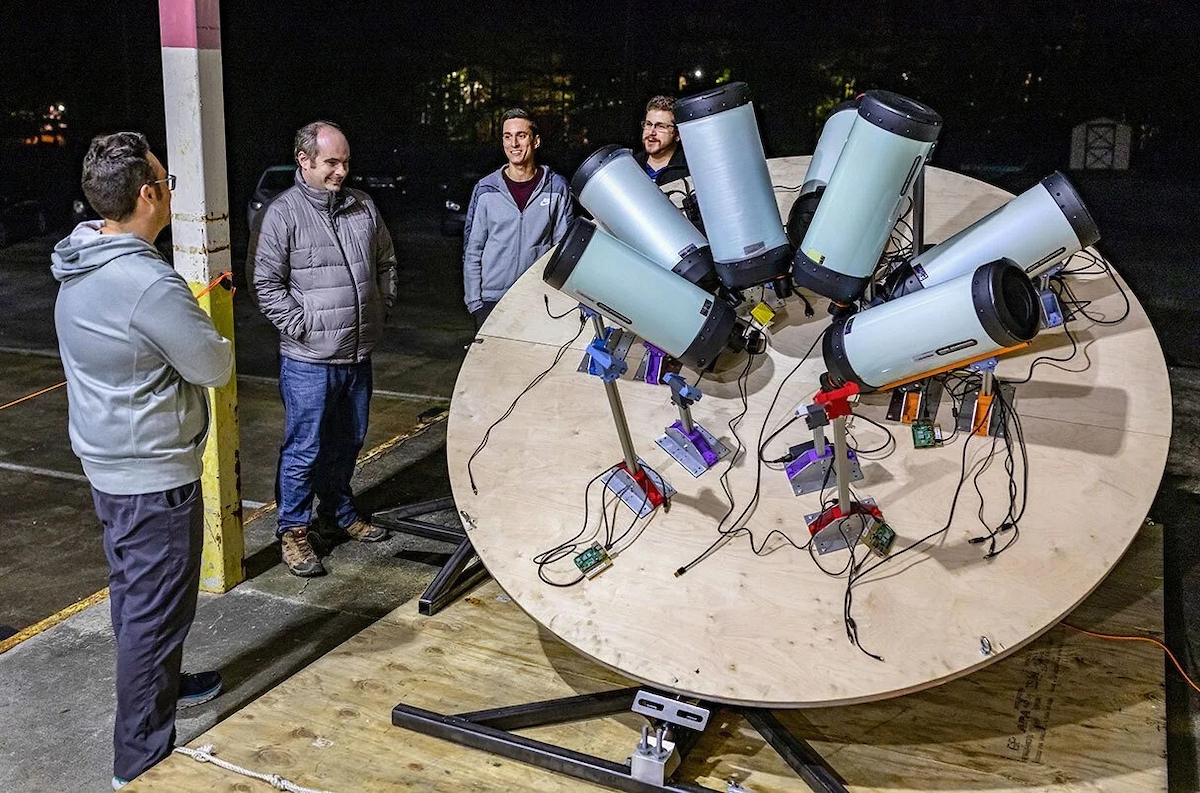

And finally, the LFAST telescope was described during the conference as "the telescope made out of many more telescopes." It's made of 20 modules with a combined collecting area equal to a telescope with a 3.5-meter (11.5 feet) mirror, according to the Schmidt Sciences website.

"We just heard about two facilities that are mostly designed to do surveys. And LFAST is a facility that we are building to do follow-up," Chad Bender of the University of Arizona said during the conference. "Because it's scalable, we can build it out as needed to support the science."

Another unique feature of LFAST is that it's an optical telescope without any large domes. "Domes are very expensive," Bender said. "But we still have to protect the mirrors — they're optical quality mirrors. So, we're building little mini domes — little cylinders, or canisters — around each telescope that fit within the frame."

"The questions that we're trying to answer are: How do we get bigger apertures, and how do we do it cheaper, and how do we do it faster?" Bender said.

Those questions seem to apply to the entire principle of Schmidt Sciences' observatory system project.

"This is an experiment in accelerating astrophysics discovery: What happens when we get technology into the hands of astronomers more quickly?" Arpita Roy, lead of the Astrophysics & Space Institute at Schmidt Sciences, said during the conference. "Our mandate, as we see it, is to build the enabling layer and open it up to all of you, to populate it with the science that will bring us into the next decade."

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.