'God of Destruction' asteroid Apophis will come to Earth in 2029 — and it could meet some tiny spacecraft

Scientists have unveiled three concepts for tiny spacecraft that could voyage from Earth to meet Apophis in April 2029.

In just under half a decade, a 1,000-foot-wide (305-meter-wide) asteroid named after the Egyptian god of chaos and destruction, Apophis, will pass within 30,000 miles (48,300 kilometers) of Earth. Scientists don't intend to allow the rare close passage of a space rock of this size to go to waste.

On April 13, 2029 — a Friday, no less — when Apophis, formally known as (99942) Apophis, makes its closest approach to Earth, it will become so prominent over our planet that it will visible with the unaided eye. NASA's OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft (once known as OSIRIS-REx) will be on hand to meet the near-Earth asteroid (NEA) personally. But, if things shape up, that NASA mission could be joined by a host of little satellites during its rendezvous.

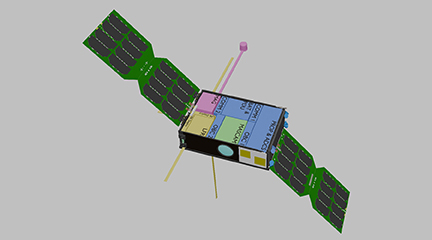

Under the auspicious "NEAlight" project, a team from Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU) and led by space engineer Hakan Kayal has revealed three concepts for such spacecraft. Each of the suggested satellites will aim to exploit this asteroid passage because Earth experiences just once such event every millennium. The goal? To collect data that could help scientists better understand the solar system, and perhaps even aid in the development of defense measures against dangerous asteroids.

Related: Asteroid Apophis will swing past Earth in 2029 — could a space rock collision make it hit us?

As to why Apophis is an apt target for a planetary defense study? Well, discovered in 2004, the asteroid quickly rose to the top of tables that measure the risk of so-called potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs), or asteroids with widths of 460 feet (140 meters) or more that come within 20 lunar distances of Earth.

Both the size of Apophis and how close to Earth its trajectory brings it saw the asteroid remain at the top of both the European Space Agency's (ESA's) "impact risk list" of PHAs and NASA's Sentry Risk Table for 17 years. That was until a close flyby of the asteroid — a space rock that is almost as wide as the Empire State Building is tall — in March 2021 allowed NASA scientists to determine Apophis actually won't hit the Earth for at least 100 years.

Though we now know Apophis won't collide with Earth in the next century, its scientific impact in 2029 will still be tremendous, and space agencies from countries across the globe will be closely tracking its trajectory.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Plus, as an asteroid that formed around the same time as the planets from leftover material around the infant sun, Apophis also offers researchers a unique opportunity to determine what the solar system's chemical composition was around 4.6 billion years ago

Meet the rendezvous candidates

Despite the fact that we are aware of around 1.3 million asteroids in the solar system, of which 2,500 are considered potentially hazardous (though none are expected to hit Earth for at least a century), spacecraft missions to study asteroids are relatively rare.

Thus far, only 20 missions have been deployed to study asteroids in situ, including the aforementioned OSIRIS-REx, Japan's Hayabusa1 and Hayabusa2 crafts, the ESA's Rosetta space probe, and the asteroid-hopping NASA mission Lucy, currently journeying to the Trojan asteroids that share their orbit with Jupiter. Thus, the JMU team must carefully consider its options when considering a future asteroid-investigating spacecraft.

The team's first concept is a small satellite that will join Apophis for a period of two months as it makes its close approach to Earth in April 2029. The craft will stick with the "God of Destruction" space rock for weeks after, even as it moves away. Over the course of the mission, this German national spacecraft will photograph Apophis and make measurements documenting any changes the NEA undergoes during its flyby.

This particular mission would be a challenging one because of its duration, the distance it will be required to travel, and the fact that the craft will have to function autonomously for long periods. It would also have to launch at least a year before Apophis arrives in Earth's vicinity.

The team's second concept involves integration with a larger spacecraft that's being planned by the ESA called RAMSES. This mission will be outfitted with smaller satellites, measuring equipment and telescopes. RAMSES, named after Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses the Great, would journey to Apophis and stay with the asteroid as it passes Earth.

If the second concept reaches fruition, one of the small satellites carried by RAMSES will be designed by the JMU team, with this project requiring less technical effort than the first concept while promising to reap greater scientific knowledge.

One of the primary issues the second concept faces, however, has to do with getting REMESES off the ground — not literally, but figuratively. It's success will depend on the willingness of ESA partner countries to fund the mission. Again, a lead time of at least 365 days would be needed to ensure the success of this concept.

The third concept involves a small satellite that will only briefly fly past Apophis when the asteroid is at its absolute closest to Earth, snapping images of the asteroid in the process. This concept would require much less effort, and the craft would be relatively inexpensive.

The downside of concept 3, however, is that its observation time would be limited, which would also limit the volume of knowledge this mission would add to our understanding of asteroids.

On the plus side, the small-scale mission could launch just two days before Apophis arrives. Also, if concept 3 were to successfully observe Apophis, it would demonstrate the capability of small and inexpensive satellites in studying asteroids, perhaps leading to an increased interest for in situ asteroid-studying missions going forward.

The NEAlight project kicked off at the beginning of May 2024; between now and April 30, 2025, the JMU scientists will work out the requirements and specificities of the respective missions.

Beyond the visit of Apophis, the three concepts considered could remain options for future missions to other solar system planets, the moon — or maybe other intriguing NEAs.

Asteroid Apophis: Frequently asked questions

How big is asteroid Apophis?

Apophis has an average diameter of around 1,115 feet (340 meters), measures some 1,480 feet (450 meters) long across its longest axis, according to NASA. Astronomers were initially able to estimate its size based on its observed brightness, but infrared telescopes were able to collect more accurate data that refined these estimates to the figures above.

In terms of mass, it's estimated that Apophis has a mass of around 88 billion pounds (40 billion kg), but these estimates are far less accurate than the estimates of its size.

What would happen if asteroid Apophis hit Earth?

An impact from an asteroid the size of Apophis would be catastrophic. The amount of energy such an impact would release would be equal to several hundred nuclear weapons, according to The Planetary Society. Such an impact would gouge out a crater around 3 miles (5 km) deep and would devastate an area hundreds of miles in diameter.

Apophis is not massive enough to destroy the planet, but certainly large enough to take out a large city. An impact in the ocean would be less catastrophic as water would help dissipate some of the energy.

How to pronounce Apophis?

Apophis is an ancient Greek name for an Egyptian god, Aphoph or Apep. Its current spelling has been Romanized (written with our alphabet) and anglicized, or adapted into English pronunciation and spelling.

So, Apophis is pronounced with the emphasis on the second syllable and sounds like the phonemes "uh-pah-fis." The 'o' is pronounced as a short 'o', while the 'a' is likewise a short 'a' sound.

Using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), Apophis can be written as "ˈæpəfɪs/."

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.