Future Space Colony? Maybe We Should Look Beyond Mars to Saturn's Titan Moon

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

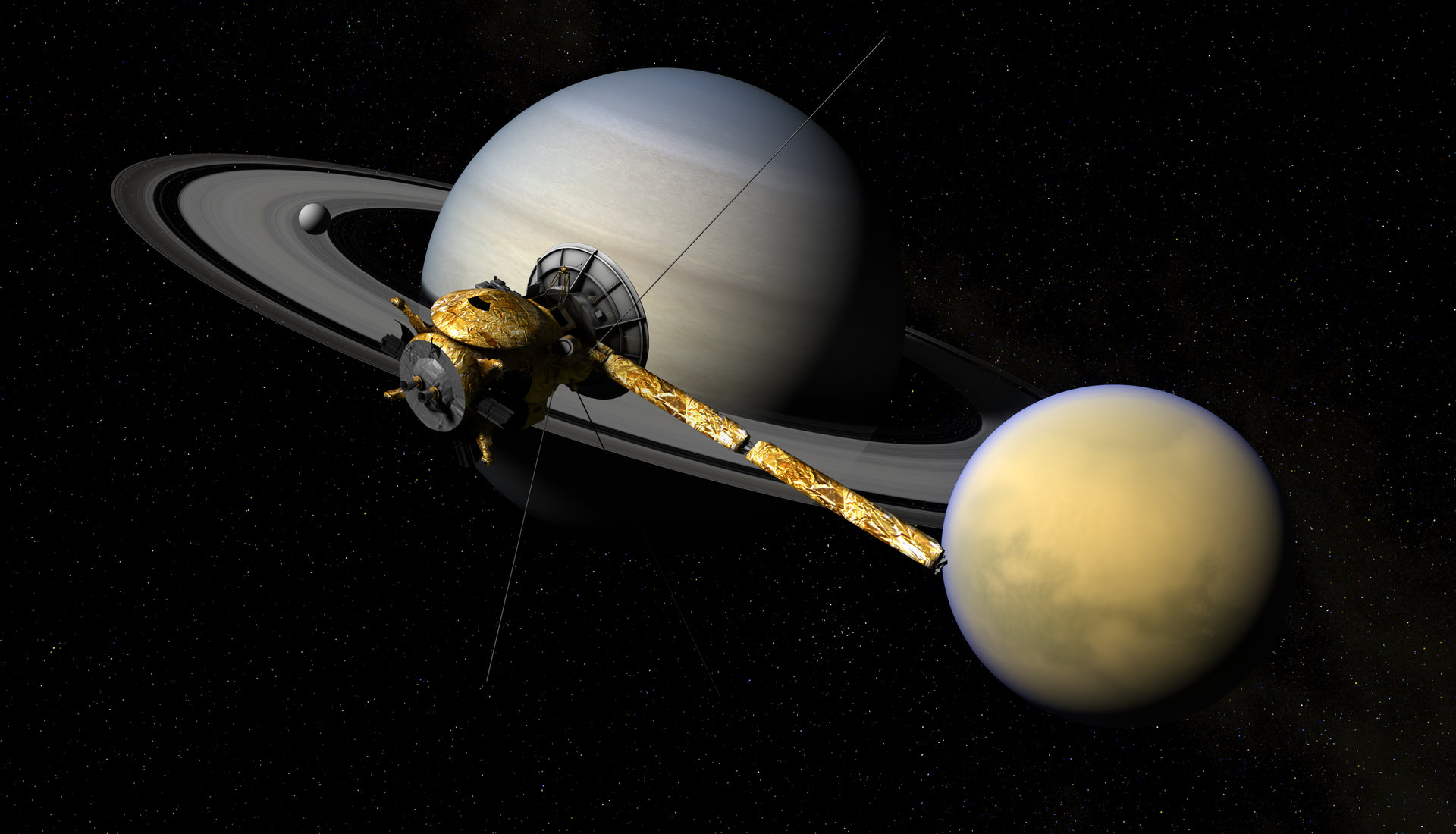

NASA and Elon Musk’s SpaceX are focused on getting astronauts to Mars and even one day establishing a colony on the Red Planet — but what if their attention is better directed elsewhere? A new paper in the Journal of Astrobiology & Outreach suggests that humans should instead establish a colony on Titan, a soupy orange moon of Saturn that has been likened to an early Earth, and which may harbor signs of "life not as we know it."

"In many respects, Saturn's largest moon, Titan, is one of the most Earth-like worlds we have found to date," NASA says on its website. "With its thick atmosphere and organic-rich chemistry, Titan resembles a frozen version of Earth, several billion years ago, before life began pumping oxygen into our atmosphere."

To be clear, Titan could have microbes — or, at the least, chemistry that resembles prebiotic life — but it is no Earth. The moon is perpetually covered in an orange cloud, and its atmosphere is not human-friendly. But Titan's gravity is walkable (14 percent that of Earth), radiation on the surface is less than on Mars due to its thick clouds, and it offers various sources from which visitors might generate energy.

As the paper's author, Amanda Hendrix, pointed out in a previous book that she co-authored, Beyond Earth: Our Path to a New Home in the Planets, Titan has massive deposits of hydrocarbons — compounds generally associated with petroleum and gas. Data from NASA's Cassini probe has shown that Titan has hundreds of times more liquid hydrocarbons than all of the known oil and natural gas reserves on Earth.

Beyond Earth points out that people on Titan could get energy from these compounds if they use a separate combustion source that helps circumvent that fact that there's no oxygen in the moon’s atmosphere. But Hendrix's new research also discusses other ways of generating chemical energy, such as treating acetylene (an abundant compound) with hydrogen.

"In this paper, I wanted to dig into the chemical energy options a bit deeper and also look into alternative energy possibilities," said Hendrix, a staff scientist at the non-profit Planetary Science Institute. "My co-author, Yuk Yung, and I looked at chemical, nuclear, geothermal, solar, hydropower, and wind power options at Titan. The paper is designed to be a high-level first look at some of these topics."

RELATED: Saturn's Titan Moon May Offer a Glimpse of Life as We Don't Know It

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Hendrix said it's possible to generate such energy using technology that we have available today, she noted that there are ways that we could get even more out of Titan’s environment with the proper study. For example, more solar power would be generated if we learned about the capabilities of different photovoltaic cell materials — and most importantly, how they would behave on Titan.

Hydro power would require better mapping of Titan's abundant lake regions, including their topography and their flow rate. Even wind power would require some research into airborne wind turbines — but Hendrix said all of these options are promising.

"I imagine that, as here on Earth, a combination of energy sources will be useful on Titan," she said. "In particular, solar energy (using large arrays) and wind power (using airborne wind turbines) may be particularly effective."

RELATED: A City on Mars: Elon Musk Details SpaceX's Plan to Colonize the Red Planet

Delivered properly, the energy needs would be more than enough for a small outpost. Instead of just sending humans on a one-shot mission to look for life on the surface, for example, Hendrix envisions a future that could generate power for years. One scenario — solar arrays over 10 percent of Titan's surface area — would generate power needs of a population of roughly 300 million, equivalent to that of the United States.

"This is just an initial estimate, of course, but what we're talking about is something much larger than a short-term human science mission to Titan," Hendrix said.

With NASA's stated goal of sending humans to Mars by the 2030s, however, space agencies remain focused on Mars exploration. While the Cassini robotic mission at Saturn and its moons wraps up observations this September, NASA and the European Space Agency are planning even more missions to Mars in the coming years. Saturn doesn't really figure into the plans, although NASA is thinking about eventual missions to Uranus, Neptune, and Jupiter's moon Europa.

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.