Endless Void or Big Crunch: How Will the Universe End?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Not only are scientists unsure how the universe will end, they aren't even sure it will end at all.

Several possibilities for the fate of our universe have been bandied about. They tend to have names such as Big Crunch, Big Rip and Big Freeze that belie their essential bleakness. Ultimately, space could collapse back in on itself, destroying all stars and galaxies in existence, or it could expand into essentially an endless void.

"The truth is that it's still an open scenario," said astrophysicist Steve Allen of Stanford University. "We certainly don't know for sure what's going to happen."

Article continues belowOn the brighter side, any eventuality will take billions or even trillions of years to occur, long after our great-great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren should be past caring. If humans are still in existence at that point, however, they may have a tough time of it. [Images: Peering Back to the Big Bang & Early Universe]

Dark energy's role

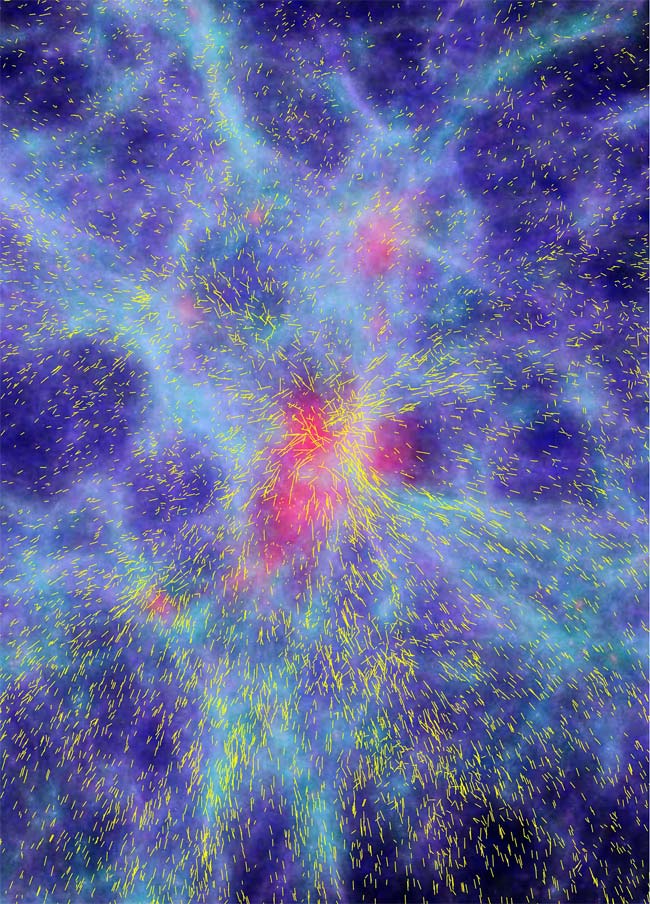

The fate of our universe largely depends on a mysterious entity dubbed dark energy. This is the name for the unexplained force that is counteracting gravity, pulling the universe apart at the seams.

Dark energy was originally discovered when scientists set out to find out how much the expansion of the universe was slowing down, due to gravity pulling it back inward. They found, instead, that this expansion is actually accelerating. This shocking discovery earned three astrophysicists the 2011 Nobel Prize.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If dark energy continues to exert the same force on the universe in the future, then space will continue to expand, the distance between galaxies stretching wider and wider and at a faster and faster pace. Eventually we won't be able to see anything beyond the Milky Way because everything will be so far away.

"Today we look up in the sky and we see just fantastic things; galaxies, clusters of galaxies stretching out all over the sky," Allen told SPACE.com. "But if the expansion is going to get faster and faster, eventually those galaxies will get pulled too far away for us to see. Space becomes an ever- less beautiful and rich place. The universe becomes a relatively lonely place."

This scenario is sometimes called the Big Freeze, because the universe will end up largely cold, dark and empty.

Placing bets

This vision is the most likely future for our universe, scientists say, because the best observations of the young, distant universe to date suggest that the strength of dark energy has remained steady throughout time.

This is in fitting with a theory that dark energy is what Einstein called the cosmological constant, a term he added to his general theory of relativity.

"Today, to the best of my knowledge, all the best data we have are consistent with a cosmological constant, consistent with dark energy being constant over time," Allen said. "If people had to bet on anything, they would bet on that."

Big Rip

But a Big Freeze isn't inevitable. If dark energy isn't a constant and instead increases over time, we could be facing what scientists call a Big Rip.

The current strength of dark energy is not thought to be enough to overcome gravity on small, local scales. However, if dark energy gets stronger, it may be enough to counteract even that, expanding not just the space between galaxies but the space within them.

"At some point galaxies themselves could be ripped apart," said Martin Bojowald, a physicist at Pennsylvania State University. "The Milky Way would be ripped apart. The question is whether it goes down even to the solar system."

Big Crunch

Another, equally dire possibility is that the strength of dark energy diminishes over time. In that case, the expansion of the universe will stop accelerating and eventually slow down. [7 Surprising Things About the Universe]

If dark energy became weak enough, gravity might ultimately win the tug of war and pull the universe back in on itself. The result would be the Big Crunch.

"The collapse initially would just be very harmless; the density of the universe would increase, but very slowly," Bojowald said. "But at some time the collapse would lead to densities of the same size as the Big Bang."

According to general relativity, at the moment of the Big Bang the universe was as small as a single point, and infinitely dense. However, most physicists think this theory is incomplete and cannot fully describe the quantum and gravitational forces going on at that time.

Thus, if the universe did crunch back in on itself, it's unclear whether it would stop once it got down to its smallest, densest state, or if some kind of repellant force would kick in, forcing space back outward and beginning the cycle all over again.

Unraveling the mystery

If scientists have any hope of solving the mystery of the universe's fate, they must get a better handle on dark energy.

"Our biggest question is, what is the dark energy?" said astrophysicist Alexey Vikhlinin of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. "All these answers sensitively depend on the physical nature of dark energy."

It's a question researchers on which do have hope of making headway, as they continue to look farther and farther away, taking more and more precise measurements of the expansion rate of the universe over time. In the next decade or so, scientists expect to be able to say with significantly more confidence whether dark energy has been constant or has changed over the 14 billion years since the Big Bang.

It's a challenge scientists relish.

"The universe is kind of humbling when you look at it and start to appreciate its scale," Allen said. "It feels like a privilege to be able to ask these questions."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.