What's 96 Percent of the Universe Made Of? Astronomers Don't Know

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

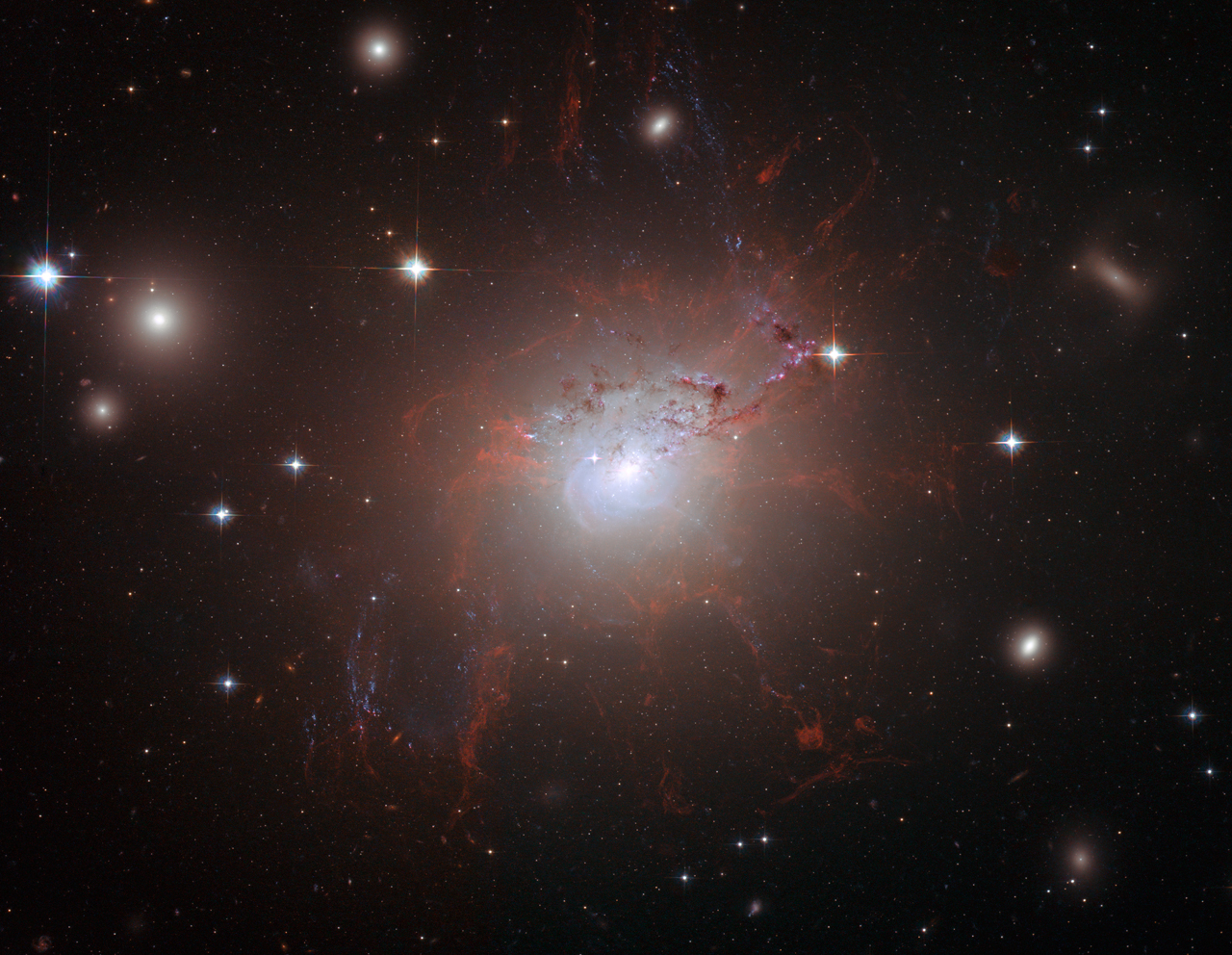

NEW YORK — All the stars, planets and galaxies that can be seen today make up just 4 percent of the universe. The other 96 percent is made of stuff astronomers can't see, detect or even comprehend.

These mysterious substances are called dark energy and dark matter. Astronomers infer their existence based on their gravitational influence on what little bits of the universe can be seen, but dark matter and energy themselves continue to elude all detection.

"The overwhelming majority of the universe is: who knows?" explains science writer Richard Panek, who spoke about these oddities of our universe on Monday (May 9) at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY) here in Manhattan. "It's unknown for now, and possibly forever."

In Panek's new book, "The 4 Percent Universe" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), Panek recounts the story of how dark matter and dark energy were discovered. It's a history filled with mind-boggling scientific surprises and fierce competition between the researchers racing to find answers. [Strangest Things in Space]

Dark matter

Some of the first inklings astronomers had that there might be more mass in the universe than just the stuff we can see came in the 1960s and 1970s. Vera Rubin, a young astronomer at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, observed the speeds of stars at various locations in galaxies.

Simple Newtonian physics predicted that stars on the outskirts of a galaxy would orbit more slowly than stars at the center. Yet Rubin's observations found no drop-off at all in the stars' velocities further out in a galaxy. Instead, she found that all stars in a galaxy seem to circle the center at roughly the same speed.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It means that galaxies should be flying apart, should be completely unstable," Panek said. "Something's missing here."

But research by other astronomers confirmed the odd finding. Ultimately, based on observations and computer models, scientists concluded that there must be much more matter in galaxies than what's obvious to us. If the stars and gas that we can see inside galaxies are only a small portion of their total mass, then the velocities make sense.

Astronomers nicknamed this unseen mass dark matter.

Where is it?

Yet, in the nearly 40 years that followed, researchers still haven't been able to figure out what dark matter is made of.

A popular hypothesis is that dark matter is formed by exotic particles that don't interact with regular matter, or even light, and so are invisible. Yet their mass exerts a gravitational pull, just like normal matter, which is why they affect the velocities of stars and other phenomena in the universe. [Video: Dark Matter in 3D]

However, try as hard as they might, scientists have yet to detect any of these particles, even with tests designed specifically to target their predicted properties.

"I think on the dark matter side there is some discouragement among the people who are kind of mid-career," Panek said. "They went into this field thinking, 'OK, we're going to solve this problem and then we'll build from there.' But 15, 20 years later, they're saying, 'I've invested my career in this and I don’t know if I'm going to find anything in my lifetime.'"

Still, many hold out hope that we're getting close and that experiments such as the newly built Large Hadron Collider particle accelerator in Geneva may finally solve the puzzle.

Dark energy

Dark energy is possibly even more baffling than dark matter. It's a relatively more recent discovery, and it's one that scientists have even less of a chance of understanding anytime soon.

It all started in the mid-1990s, when two teams of researchers were trying to figure out how fast the universe was expanding, in order to predict whether it would keep spreading out forever, or if it would eventually crumple back in on itself in a "Big Crunch."

To do this, scientists used special tricks to determine the distances of many exploded stars, called supernovas, throughout the universe. They then measured their velocities to determine how fast they were moving away from us.

When we view very distant stars, we are viewing an earlier time in the history of the universe, because those stars' light has taken millions and billions of light-years to travel to us. Thus, looking at the speeds of stars at various distances tells us how fast the universe was expanding at various points in its lifetime.

Astronomers predicted two possibilities: either the universe has been expanding at roughly the same rate throughout time, or that the universe has been slowing in its expansion as it gets older.

Shockingly, the researchers observed neither possibility. Instead, the universe appeared to be accelerating in its expansion.

That fact could not be explained based on what we knew of the universe at that time. All the gravity of all the mass in the cosmos should have been pulling the universe back inward, just as gravity pulls a ball back down to Earth after it's been thrown into the air.

"There's some other force out there or something on a cosmic scale that is counteracting the force of gravity," Panek explained. "People didn't believe this at first because it's such a weird result."

Fierce competition

Scientists named this mysterious force dark energy. Though no one has a good idea of what dark energy is, or why it exists, it is the force that appears to be counteracting gravity and causing the universe to accelerate in its expansion.

The lack of a good explanation for dark energy hasn't seemed to dampen scientists' enthusiasm for it.

"What I hear again and again is how excited people are to be working in this field right now, when this revolution is going on," Panek told SPACE.com. "The problems are so great and profound, they're actually rather thrilled with it."

Overall, dark energy is thought to contribute 73 percent of all the mass and energy in the universe. Another 23 percent is dark matter, which leaves only 4 percent of the universe composed of regular matter, such as stars, planets and people.

This bizarre, but apparently true, conclusion was reached at about the same time by the two groups working to measure the expansion of the universe. The competition between the groups became very contentious, Panek said, and they grew to dislike each other quite a lot.

Ultimately, though, members of both teams should reap the rewards of finding one of the biggest surprises in the history of science.

"I think that it's kind of assumed the dark energy will win the discoverers the Nobel," Panek said. "There certainly is that assumption that it's just a matter of years."

You can follow SPACE.com Senior Writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.