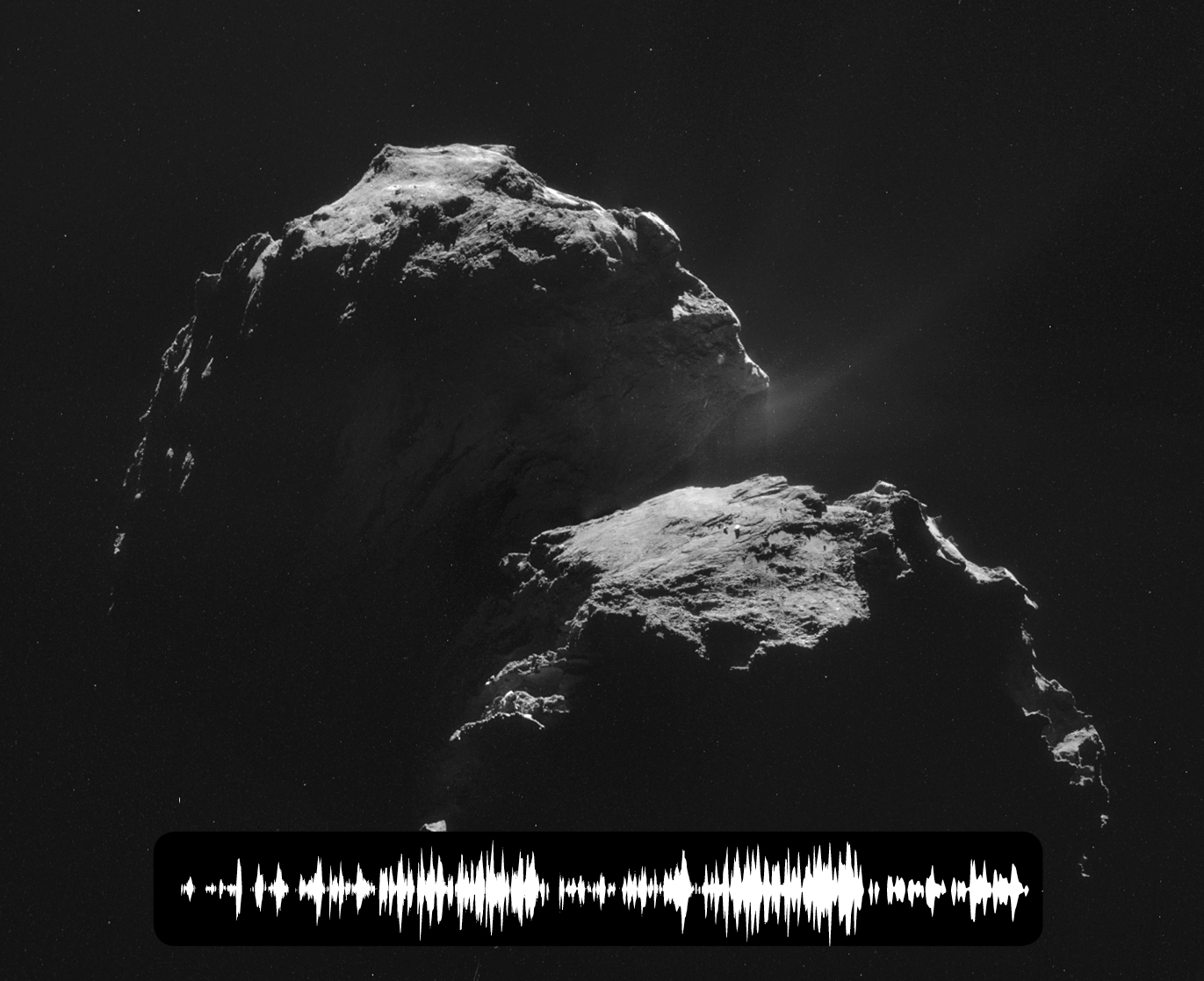

Listen to This: Comet's Eerie 'Song' Captured by Rosetta Spacecraft

Scientists have picked up on the mysterious "song" of a comet speeding through deep space.

European Space Agency officials have used their Rosetta spacecraft to listen to a sound emitted by Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The comet song capture by Rosetta is produced by "oscillations in the magnetic field in the comet's environment," ESA officials said in a statement.

The Rosetta spacecraft was able to pick up the strange, echoed clopping sound, but if a human were floating through space next to the comet, he or she wouldn't hear anything at all. Comet 67P/C-G is singing well below the frequency that the human ear can hear, according to ESA. The frequency of the sound was increased by a factor of approximately 10,000 for an audible rendering of the comet's tune. [Rosetta Mission's Comet Landing: Full Coverage]

The scientists that discovered the sound still aren't exactly sure how it's created, though they have some ideas. ESA scientists think that the sound could be produced when neutral particles of the comet are sloughed off into space and electrically charged through ionization, but officials still aren't sure how the physics of the oscillations work.

"This is exciting because it is completely new to us," Karl-Heinz Glaßmeier, head of Space Physics and Space Sensorics at the Technische Universität Braunschweig, Germany, said in a statement. "We did not expect this and we are still working to understand the physics of what is happening."

Rosetta's magnetometer experiment first recorded the song when it was flying within about 62 miles (100 kilometers) of the comet in August. The magnetometer is part of a five-instrument suite, called Rosetta's Plasma Consortium (RPC). The instruments are designed to monitor how the comet interacts with the solar wind and plasma emitted by the sun. The RPC also looks at the structure of the comet's atmosphere, known as a "coma." (Glaßmeier is also the principal investigator for the RPC.)

Tomorrow (Nov. 12), Rosetta is expected to release its Philae lander down to the surface of Comet 67P/C-G. If it works, the landing will mark the first time humans have soft-landed a probe on the face of a comet. You can keep up with the landing in a live Philae webcast on Space.com

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Rosetta and Philae will be responsible for gathering data about the comet to help scientists learn more about the icy wanderers, remnants from when the solar system formed billions of years ago. Rosetta should keep studying the comet from orbit until December 2015, after its close approach with the sun in August. If Philae's landing is successful, it should be able to study the comet from its landing site until March 2015.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.