Definition of Life: Debate Still Swirls Around Arsenic Claim

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Life on Earth is composed of a handful of essential elements from the periodic table. Recently, one group of researchers claimed that this ingredient list should be expanded, having found a bacteria that presumably switches poisonous arsenic in for phosphorous.

Other scientists are skeptical, but they still entertain the thought of switching the rules in the biochemistry playbook.

The human body contains around 60 elements, but only about a third of those are considered necessary for survival. Looking across all species, the most fundamental elements are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorous and sulfur, since these make up the basic molecules of terrestrial life: DNA, proteins and carbohydrates.

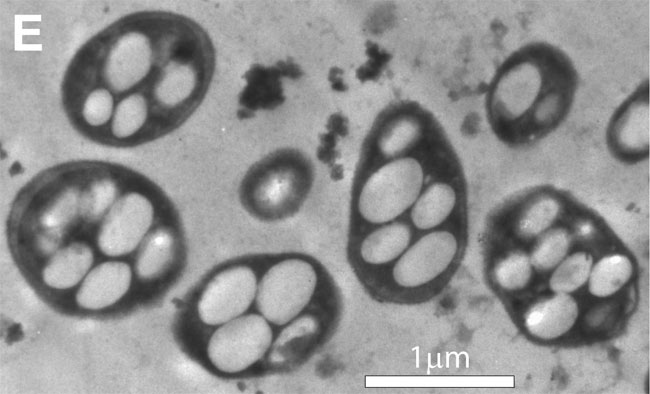

This is why the little microbe, GFAJ-1, has caused such a stir. It was isolated from arsenic-rich Mono Lake in California by Felisa Wolfe-Simon of the NASA Astrobiology Institute and her colleagues. In a recent Science journal paper, the researchers reported that GFAJ-1 can apparently build its DNA and proteins using arsenic in the spots usually held by phosphorus.

Arsenic is located right below phosphorous in the periodic table, because their chemistries are similar. But that is exactly why arsenic is so deadly: it replaces phosphorous in chemical reactions, but the resulting arsenic compounds are a poor substitute.

The GFAJ-1 claim "seems to be incompatible with 150 years of understanding the chemistry of arsenic," says William Bains of Rufus Scientific in Cambridge, UK and MIT.

Many scientists like Bains contend that GFAJ-1 survives in arsenic-rich conditions by sequestering the element somewhere in its cell. They don't believe there's enough proof yet to say that the bacteria is actually encoding its genes on arsenic-laced DNA.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Arsenic DNA is exceptional, so it demands exceptional evidence," says Steve Benner of the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution.

However, Benner and Bains are not immune to the idea of life written out with a different chemical formula. They just think it's probably happening on an entirely different world.

Biochemistry on Titan

Benner for his part has tried to fabricate arsenic DNA in the lab, but without any luck. He blames it on the fact that arsenic esters break down a million billion times faster than phosphorous esters. (These esters are needed to make the DNA backbone.)

However, this doesn't completely rule out a role for arsenic in biology. On Saturn's moon Titan, where temperatures hover around minus 180 degrees Celsius, arsenic could make a fine replacement.

"Phosphorous-containing molecules would be too stable on Titan," Benner says. "The reactivity of arsenic in this case becomes a virtue."

Titan has other properties that make it an interesting test-bed for alternative life theories. Dirk Schulze-Makuch of Washington State University has considered the lakes of liquid methane and ethane that dot the Titan landscape.

"We can ask: what could make a living there?" Schulze-Makuch says. "How different can the life be?"

Methane has often been considered as a possible substitute for water as a life-sustaining liquid. Large complex molecules often disintegrate in water, but that is less of a problem in methane and other hydrocarbon solvents, explains Schulze-Makuch. Another difference is that carbon might not be the only element of choice.

"Silicon works nicely with methane," says Schulze-Makuch.

Silicon sits underneath carbon in the periodic table, so it can form many of the same complex molecular structures that carbon is famous for.

Silicon is the second most abundant element in the Earth's crust (outnumbering carbon atoms by a factor of 1000), and yet none of our neighbors are silicon-based life-forms. The reason is that silicon typically forms silicon oxides in water, and these oxides eventually turn into rock, which is a dead-end for silicon biochemistry.

But in a cold landscape where water is frozen, one can imagine silicon analogues of our biochemicals emerging from a primordial soup of liquid methane or liquid nitrogen. Bains is currently studying this very possibility.

Extremes of habitability

This is all familiar terrain for Star Trek fans. In the "Devil in the Dark" episode from 1967, Dr. Spock befriends a silicon-based life form called the Horta.

An even earlier attempt at imagining the limits of alien biochemistry was the 1953 sci-fi novel Iceworld by Hal Clement, in which a super-hot planet hosts life that breathes gaseous sulfur and drinks copper chloride.

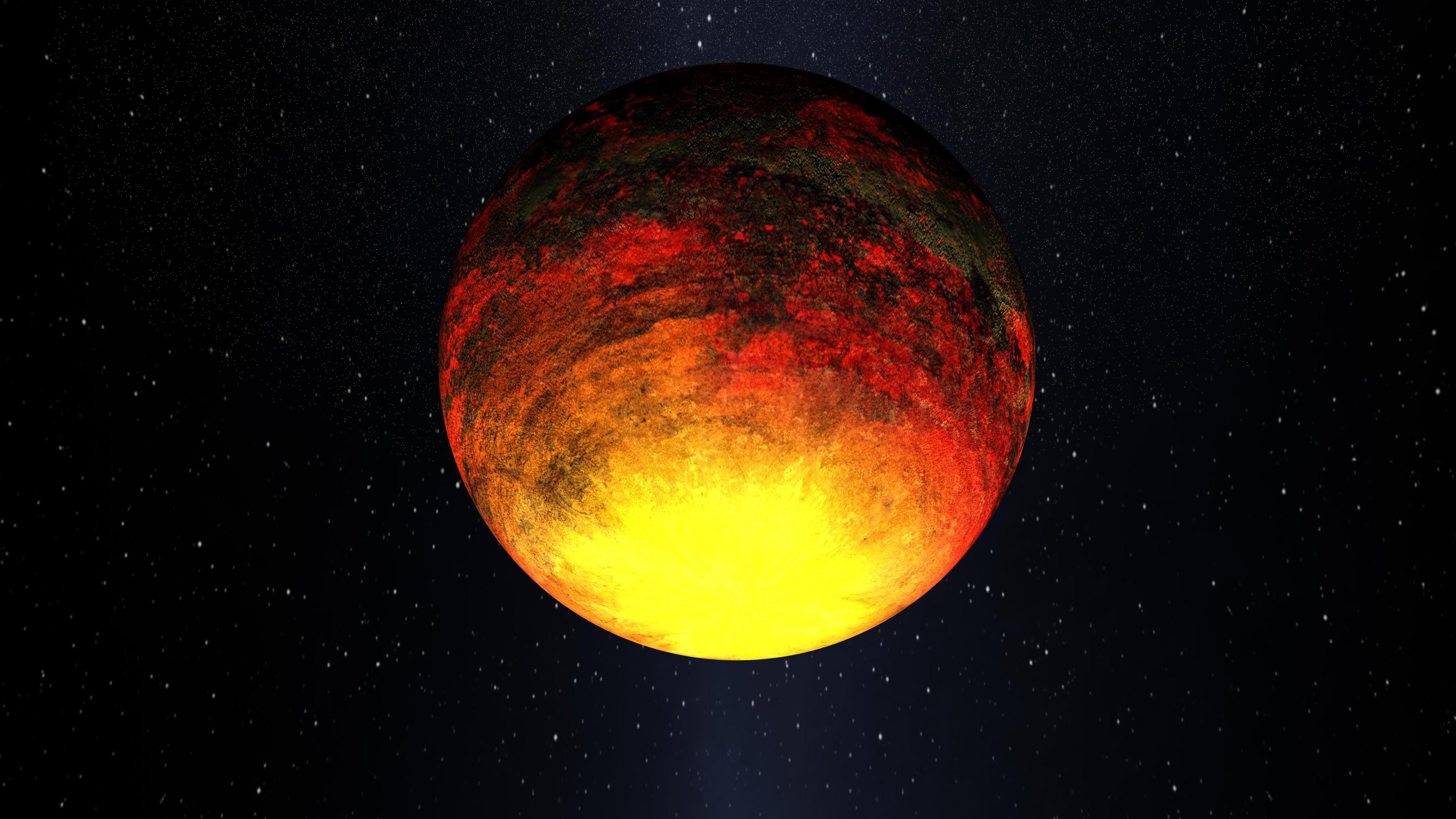

We now have proof that super-hot planets like this exist and are perhaps quite common. The first confirmed rocky exoplanet, Kepler 10b, orbits so close to its host star that surface temperatures are estimated to rise above 1,000 degrees Celsius, enough to melt iron.

"Is it reasonable to look for life on the dayside of Kepler 10b?" asks Bains. He doesn't think it is, but pondering life in seemingly impossible environments can help astrobiologists narrow their search.

"If people like me can spend a few person-years trying to figure out whether life on Pluto is impossible or not, and save the observational astronomers years of work and NASA hundreds of millions of dollars in new satellites looking for it, that seems an effort worth making," Bains says.

Reshuffling the chemistry deck

Besides silicon, other element swaps have also been considered. A combination of nitrogen and phosphorous can form a diverse set of long-chain molecules and therefore might replace carbon on, for example, a planet with an ammonia atmosphere. Boron, too, has carbon-like properties, but there's relatively little of this light element in the universe.

The role of oxygen in organic chemistry could be filled by chlorine or sulfur. Indeed, some microbes are known to occasionally replace one oxygen in their DNA with sulfur. What's even more common is sulfur itself losing its spot to selenium in particular proteins.

However, Bains and Schulze-Makuch stress that the swapping that scientists have observed in Earth's biology is only occasional. None of these organisms could survive a complete substitution. As a matter of fact, experiments have shown that replacing hydrogen with its isotope deuterium will sicken a microbe and even kill a larger animal. This is somewhat surprising since deuterium has essentially the same chemical properties as hydrogen.

"Any switching of elements has got to be accompanied with major changes in everything else," Benner says.

So if you plan to dream up your own hypothetical biochemistry, you are going to need to start from scratch and show how your elemental ingredients can come together to make a diverse set of large molecules that evolution can play with.

"We should be very open-minded when we only know of one kind of life," says Schulze-Makuch. "Let's not check anything off the list yet."

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.

Michael Schirber is a freelance writer based in Lyons, France who began writing for Space.com and Live Science in 2004 . He's covered a wide range of topics for Space.com and Live Science, from the origin of life to the physics of NASCAR driving. He also authored a long series of articles about environmental technology. Michael earned a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Ohio State University while studying quasars and the ultraviolet background. Over the years, Michael has also written for Science, Physics World, and New Scientist, most recently as a corresponding editor for Physics.