New moon of January 2026 brings prime views of Jupiter, Saturn and winter stars tonight

With the moon out of the way on Jan. 18, bright Jupiter and Saturn become stand-outs in the January night sky.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The new moon of January will be at 2:52 p.m. EST (1952 GMT) on Jan. 18, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory.

A new moon is, technically, a conjunction of the sun and moon. The two bodies share the same celestial longitude — if one drew a north-south line from the North Celestial Pole (right near where the Pole Star, Polaris, is located) the sun and moon would both be on it.

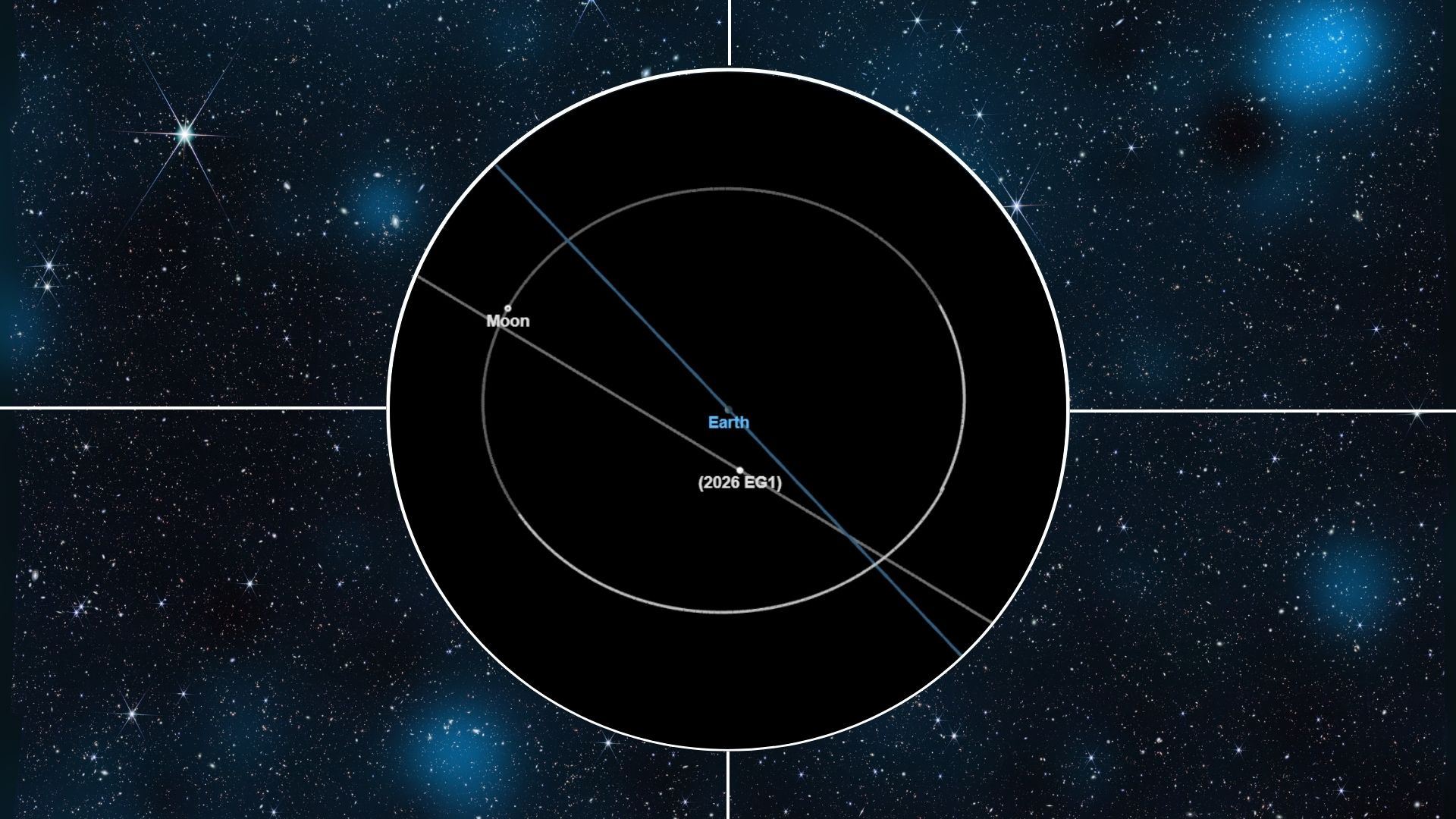

At the new phase, you can't see the moon from Earth unless there is a solar eclipse, the illuminated side is facing away from us. On top of that new moons rise and set with the sun; even if one could light up the side of the moon facing Earth it would be lost in the solar glare. Earth-based observers won't (visually) see a new moon until Feb.17, when there will be a solar eclipse visible from the southern Indian Ocean and Antarctica.

Article continues belowNew moon skies are dark, especially when compared to nights when the moon is out; even a half-moon (when the moon is at first or last quarter phase) is the second brightest object in the sky after the sun. That means the nights on either side of a new moon are good for observing fainter stars and seeing the naked-eye nebulas and star clusters, particularly if one can watch the sky from a place away from city lights.

Visible planets

On the night of Jan. 18, there will be two planets visible: Saturn and Jupiter. By about 6 p.m., Saturn will be about 37 degrees above the southwestern horizon. In New York City, the sun sets at 4:56 p.m.; the timing and Saturn's location in the sky will be similar for anyplace near 40 degrees north, such as Chicago, Denver, Detroit, or Sacramento. In New York, Saturn sets at 9:48 p.m.

Jupiter, meanwhile, rises at 3:58 p.m.; since the sky darkens completely by about 6 p.m., one will see Jupiter about 21 degrees high in the east. Jupiter is brighter than the surrounding stars; one way to identify Jupiter is look for a rough triangle of "stars" with two of them to the left (north) of a brighter one; the brighter, steadier light is Jupiter. Jupiter is visible almost all night; the planet does not set until 6:49 a.m. (January 19) in New York, and it reaches its highest altitude (called transit) at 11:23 p.m. Jan. 18.

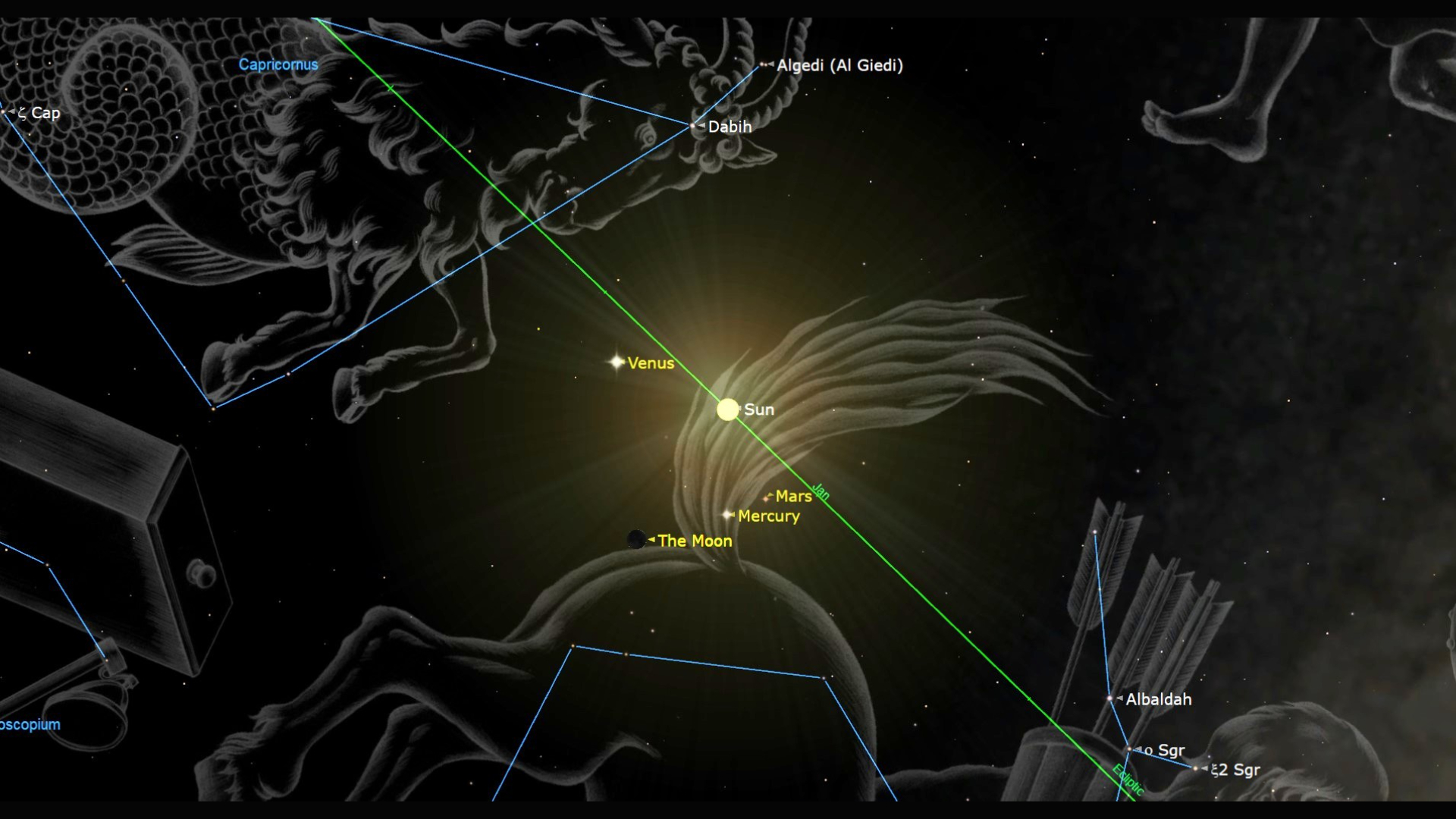

Unfortunately for planet hunters, Mercury, Venus and Mars are all too close to the sun to observe; they will come out of the solar glare in the weeks following the new moon. Mercury will emerge as an "evening star" in February and Venus will do so in March. Mars will emerge into the predawn skies in March.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For Southern Hemisphere skywatchers, the sky doesn't get dark until 9:30 p.m.; as it is the austral summer, the sun sets late. In Santiago, Chile, for example, sunset isn't until 8:54 p.m. local time on Jan. 18. Santiago is about as far south of the equator — 33 degrees — as Dallas or Charleston, South Carolina is north of it, and is of a similar latitude to cities such as Cape Town and Melbourne, Australia.

From Santiago, Saturn will be 22 degrees high in the west by 10 p.m. The ringed planet sets at 11:54 p.m. Jan. 18. Jupiter, meanwhile, rises at 8:11 p.m. local time, and by 10 p.m. is in the northeastern sky about 18 degrees high.

Stars and constellations

Winter constellations are in full swing for Northern Hemisphere observers in the latter half of January. Two hours after sunset — at about 7 p.m. in New York— some of the brightest constellations have risen — Orion (the Hunter), Gemini (the Twins), Taurus (the Bull), Canis Minor (the Little Dog) and Auriga (the Charioteer). Look low in the southeast to spot the brightest star in the sky, Sirius, the alpha star of Canis Major, the Big Dog.

You can start by identifying Gemini, as this is the constellation Jupiter is in. The two stars to the left (north) of Jupiter are Castor and Pollux, with Pollux being the one closer to the horizon. almost level with Jupiter. If you look down and to the right about four times Jupiter's distance from Pollux, you will see a bright white star; this is Procyon, the brightest star in Canis Minor. Go further to the right (south) and you see Sirius, which is recognizable by its blue-white hue and its brightness.

Directly above Sirius, about a third of the way from the horizon to the zenith (the point directly overhead) is Orion. Orion can be identified by the three stars that make up his belt — early in the night, they will appear to make an almost vertical line. Going up from the horizon, the first star is Alnitak, the second is Alnilam, and the third is Mintaka. Look slightly up and to the left of the belt and one can spot a bright reddish-orange star. This is Betelgeuse (pronounced like beetle-juice), marking one of Orion's shoulders. Above and to the right of Betelgeuse is Bellatrix, his other shoulder. On the right side of Orion's Belt, about the same distance from Mintaka as Betelgeuse is from Alnitak, is a bright blue-white star; this is Rigel.

Since the night will be moonless, just to the right of Orion's Belt and below it, you can, from a dark-sky location away from city lights, trace a group of faint stars that is Orion's sword, and in that group, you might be able to spot the Orion Nebula.

Look above Orion and go two-thirds of the way to the zenith to spot another reddish star, though its color is much less vivid than Betelgeuse. This is Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus. Aldebaran is in a group of fainter stars (the shape is a little bit like a U on its side or a backwards C). This is the Hyades, an open star cluster. Look higher still, almost straight up from Aldebaran, to see a tiny cluster of stars that are almost too close together to separate with the naked eye. This is the Pleiades, another open cluster also called the Seven Sisters. In binoculars, it will look like a miniature version of the Big Dipper.

Speaking of which, if you draw a line through Jupiter and Pollux northwards, you'll reach the Big Dipper, a group of stars that is part of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The Dipper will be close to the horizon, with the bowl facing upwards. You can use the two stars at the front of the bowl, Dubhe and Merak (with Merak being the lower one), to find Polaris, the Pole Star.

By 9 p.m. The Big Dipper is almost vertical and in the northeast; the "bowl" faces west (left). The Dipper can now be used to point to other stars besides Polaris. If you draw a line to the right, connecting the stars at the back of the bowl (these will be the two lower in the sky) you'll reach Regulus, the brightest star in Leo, the Lion, which will be almost due east and about 17 degrees high (this will vary depending on one's exact latitude but it will be similar in any mid-Northern latitude city).

For Southern Hemisphere observers, January is when Puppis, Carina and Vela, the three constellations that make up the Argo, the famous ship of Jason and the Argonauts, are prominent, rising in the east by 10 p.m. Though you'll see an "upside down" sky, you can still use Jupiter to orient — Pollux will appear to be directly below the planet, as opposed to being to the left of it, and Procyon is to the right of Jupiter and above it, some 27 degrees high in the northeast. Look up and to the right from Procyon and you will see Sirius, about 51 degrees high. Look to the right (southwards) and still higher — about 59 degrees, or two thirds of the way to the zenith, and one spies Canopus, the alpha Star of Carina, the Ship's Keel. Below Canopus, there is a large "loop" of seven medium-bright stars, the topmost one (closest to Canopus) is called Regor, or Gamma Velorum, the brightest star in Vela, the Sail. Above and to the right of Vela is Puppis, the Poop Deck, another group of seven stars in an elongated shape rather like a peanut. The first four stars form a four-sided diamond shape to the left of and below Canopus; these are relatively faint. Just to the left of Regor is a fifth star, Zeta Puppis (or Naos) and the remaining two are to the left of that about twice as far from Regor as Naos is.

About 13 degrees above the south-southeastern horizon you can see Crux, the Southern Cross, which from the latitude of Santiago is circumpolar — it never sets. At 10 p.m. it is upside down (or nearly so) so the crossbar is closer to the horizon and its brightest star, Acrux, is highest.

If you look southwest and about 54 degrees above the horizon, you can see a bright star in a patch of sky that seems to have few of them; this is Achernar, the end of Eridanus, the River. Achernar is not visible from much of the Northern Hemisphere but the end of the constellation Eridanus is — it starts just to the south of Orion's foot, Rigel, which from the latitude of Santiago is 61 degrees high in the north-northeast, with Orion's Belt below rather than above it.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.