Sirius: The brightest star in Earth's night sky

Discover Sirius, the Dog Star, the brightest star in the night sky and learn how to spot it, its history, and why astronomers study it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Sirius, also called the Dog Star, is the brightest star in Earth's night sky.

Shining more brilliantly than any other star visible from Earth (excluding our sun, of course), Sirius is outshone only by the moon, a few planets and the International Space Station in the night sky.

Its name comes from the Greek word for "glowing", an apt description for this dazzling beacon, located just 8.6 light-years away. Ancient cultures tracked Sirius for thousands of years, but astronomers were surprised in 1862 to discover that the star we see with the naked eye, Sirius A, has a faint companion, Sirius B, a tiny but dense white dwarf.

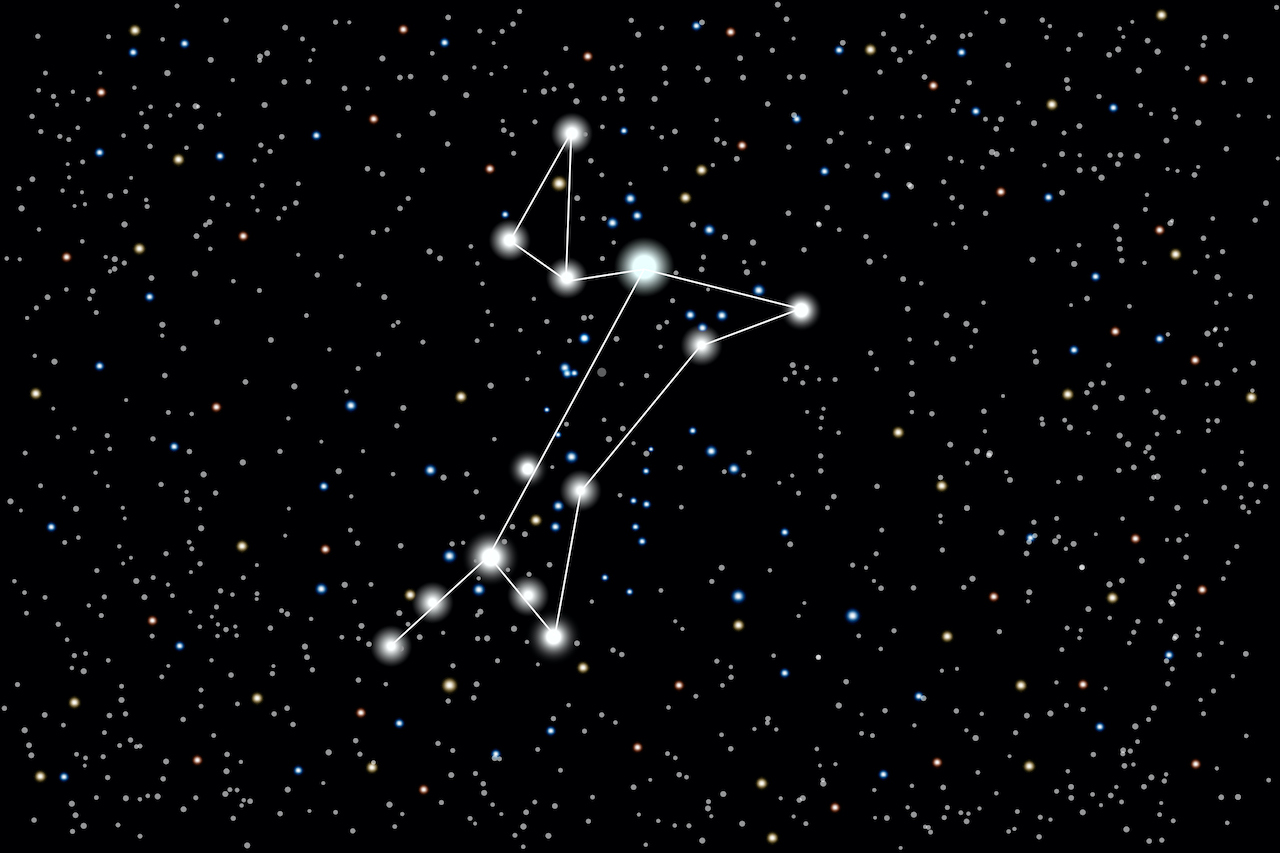

How to find Sirius in the night sky

- Right ascension: 6 hours 45 minutes 8.9 seconds

- Declination: -16 degrees 42 minutes 58 seconds

For northern observers, Sirius dominates the winter sky. The easiest way to spot it is to follow the line of Orion’s Belt, the three bright stars in a row, down and to the left. That path leads directly to Sirius, which sparkles in the constellation Canis Major (“the greater dog”).

In the Southern Hemisphere, Sirius appears high overhead during summer evenings. For both hemispheres, the star is best seen when it’s highest in the sky, away from the horizon where atmospheric turbulence is strongest.

For precise viewing, stargazing apps like SkySafari or Stellarium can help you locate Sirius from any location and date.

Sirius Expert Q&A

Curator and Professor, Department of Astrophysics, Division of Physical Sciences, at the American Museum of Natural History.

We asked Michael Shara, a curator in the American Museum of Natural History's Department of Astrophysics, a few frequently asked questions about Sirius.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Why is Sirius so bright?

Sirius is 25 times more luminous than our sun and just 8.6 light years distant. This combination of high intrinsic luminosity and closeness explains Sirius' brightness.

Why does Sirius appear to twinkle?

We see Sirius through our atmosphere, which is turbulent. Tiny differences in the amount of air every fraction of a second between us and Sirius cause the twinkling. Out in airless space, stars never twinkle.

Why does Sirius seem to be so colorful?

The air in our atmosphere spreads out (or "disperses") different colors of light by different amounts, creating a rainbow effect for all stars. This is most easily seen by our eyes in the case of Sirius because it's so bright.

Why is Sirius of interest to the astronomy community?

Sirius is the closest star that's more massive and a lot more luminous than our sun. Just as important, Sirius has the closest-known "white dwarf," a stellar "corpse," as a binary companion. That companion, referred to as Sirius B, has a mass equal to that of our sun, but it's 100 times smaller and thus a million times denser than our sun.

Are there any scientific mysteries surrounding Sirius that researchers would like to solve?

Historical records from the Alexandrian astronomer Claudius Ptolemy (around the year 150 AD) suggest that Sirius was a red star in the past (it is very hot and white today). There is no accepted explanation of how this could have happened.

Sirius in history and culture

Today, Sirius is nicknamed the "Dog Star" because it is part of the constellation Canis Major, Latin for "the greater dog." The expression "dog days" refers to the period from July 3 through Aug. 11, when Sirius rises in conjunction with the sun, Space.com previously reported. The ancients felt that the combination of the sun during the day and the star at night was responsible for the extreme heat during mid-summer.

The star is present in ancient astronomical records of the Greeks, Polynesians and several other cultures. The Egyptians even went so far as to base their calendar on when Sirius was first visible in the eastern sky, shortly before sunrise. According to Joe Rao of Space.com, the Egyptians called Sirius the "Nile Star," because it always returned just before the river rose and so announced the coming of the floodwaters that would nourish their lands.

In 1718, English astronomer Edmond Halley discovered that stars have "proper motion" relative to one another, according to the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. This means that stars, including Sirius, move across our sky with a predictable angular motion with respect to more distant stars.

More than 100 years after Halley's finding, in 1844, German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel published a scientific note in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society describing how Sirius had been deviating from its predicted movement in the sky since 1755. Bessel hypothesized that an unseen companion star affected Sirius' motion. Alvan Graham Clark, a U.S. astronomer and telescope maker, confirmed Bessel's hypothesis in 1862 when he spotted Sirius B through Clark's newly developed great refractor telescope.

Common misconceptions about Sirius

- It's not red: Some ancient records describe Sirius as red, but today it is a white star. The reason for this historical discrepancy remains a mystery.

- It's not the largest star: Sirius is bright because it’s nearby and luminous, not because it’s the largest. Many stars are much bigger.

- It's not the only Dog Star: Other stars in Canis Major and Canis Minor have also been called “dog stars” in various cultures.

Why Sirius matters to astronomers

Sirius is the closest example of a binary system with a white dwarf, making it a valuable laboratory for studying stellar evolution, mass–luminosity relationships, and the cooling of white dwarfs. Its brightness also makes it useful for calibrating astronomical instruments and testing observing techniques.

Although no planets have been found around Sirius, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has used its data to search for exoplanets around similarly bright stars.

Sirius B is a white dwarf star, which is the last observable stage of a low- to medium-mass star. White dwarfs get dimmer and dimmer until they eventually stop burning and go dark, thus becoming black dwarf stars, the theoretical final stage of a star's evolution. Scientists study white dwarfs like Sirius B in hopes of gaining a better understanding of the stellar cycle. Eventually, Earth's sun will cycle to the white dwarf stage as well.

The mass of a star is an important factor in the object's stellar evolution because it determines the star's core temperature and how long and hot the star will burn. Astronomers can calculate the mass of a star based on its brightness, or luminosity, but this was challenging for Sirius B. The luminosity of Sirius A overpowered ground-based observations, making it impossible to isolate the much dimmer luminosity coming from Sirius B, according to the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

It wasn't until 2005 when a team of astronomers assembled data collected by the Hubble Space Telescope that scientists were able to measure the mass of Sirius B for the first time. They found that the star has a mass that is 98% that of Earth's sun.

To this day, Sirius continues to be a favored study subject for astronomers and physicists.

In April 2018, NASA launched the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), with the aim of its primary mission being to find exoplanets orbiting bright stars. Because Sirius is a young star, it's not likely to have planets orbiting it. TESS discovered 66 new exoplanets, according to NASA Exoplanet Exploration, but none have been discovered orbiting Sirius.

Additional resources

You can read about Hubble Space Telescope's image of Sirius A and its companion Sirius B on the European Space Agency (ESA) website. To learn more about the Canis Major and Canis Minor constellations, watch this video from Lowell Observatory.

Bibliography

"Edmond Halley– a Commemoration". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 34 (1993). https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1993QJRAS..34..135H

"On the variations of the proper motions of Procyon and Sirius". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1844MNRAS...6R.136B

"On the Luminosity of the Companion of Sirius". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1930PASP...42..155V

"Sirius". Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics (2001). https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000eaa..bookE2394M

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.