Europe's Philae comet lander made a 2nd touchdown in a spooky spot: 'Skull-Top Ridge'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Scientists have found the second place where a bouncing European lander touched down on a comet six years ago — a discovery that's shedding considerable light on the icy wanderer's composition.

The Philae lander, part of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Rosetta mission, deployed from its mothership on Nov. 12, 2014 and headed down for the first-ever soft touchdown on the surface of a comet, the 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometers) Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Philae managed to notch that milestone, but the landing didn't exactly go according to plan. The 220-lb. (100 kilograms) lander's anchoring harpoons failed to fire properly, and Philae bounced off Comet 67P in two different places before coming to a rest in a dark cave-like structure two hours after first contacting the surface. (The comet's gravitational pull is 50,000 times weaker than that of Earth, so things that bounce there tend to stay up a while.)

Article continues belowRelated: Best close encounters of the comet kind

Philae couldn't snag enough sunlight in its final location to recharge its secondary battery, so the lander collected science data for only a few days. Still, the lander's varied observations have helped scientists better understand 67P and comets in general.

The Rosetta team quickly spotted Philae's first touchdown site in imagery captured by the Rosetta orbiter mothership, which began circling Comet 67P in August 2014. Philae itself was found in September 2016 after an extensive imagery search, but the location of the second touchdown site had remained elusive.

"Philae had left us with one final mystery waiting to be solved," ESA's Laurence O'Rourke, who led the successful hunt for Philae, said in a statement. "It was important to find the touchdown site, because sensors on Philae indicated that it had dug into the surface, most likely exposing the primitive ice hidden underneath, which would give us invaluable access to billions-of-years-old ice."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Touchdown at 'Skull-Top Ridge'

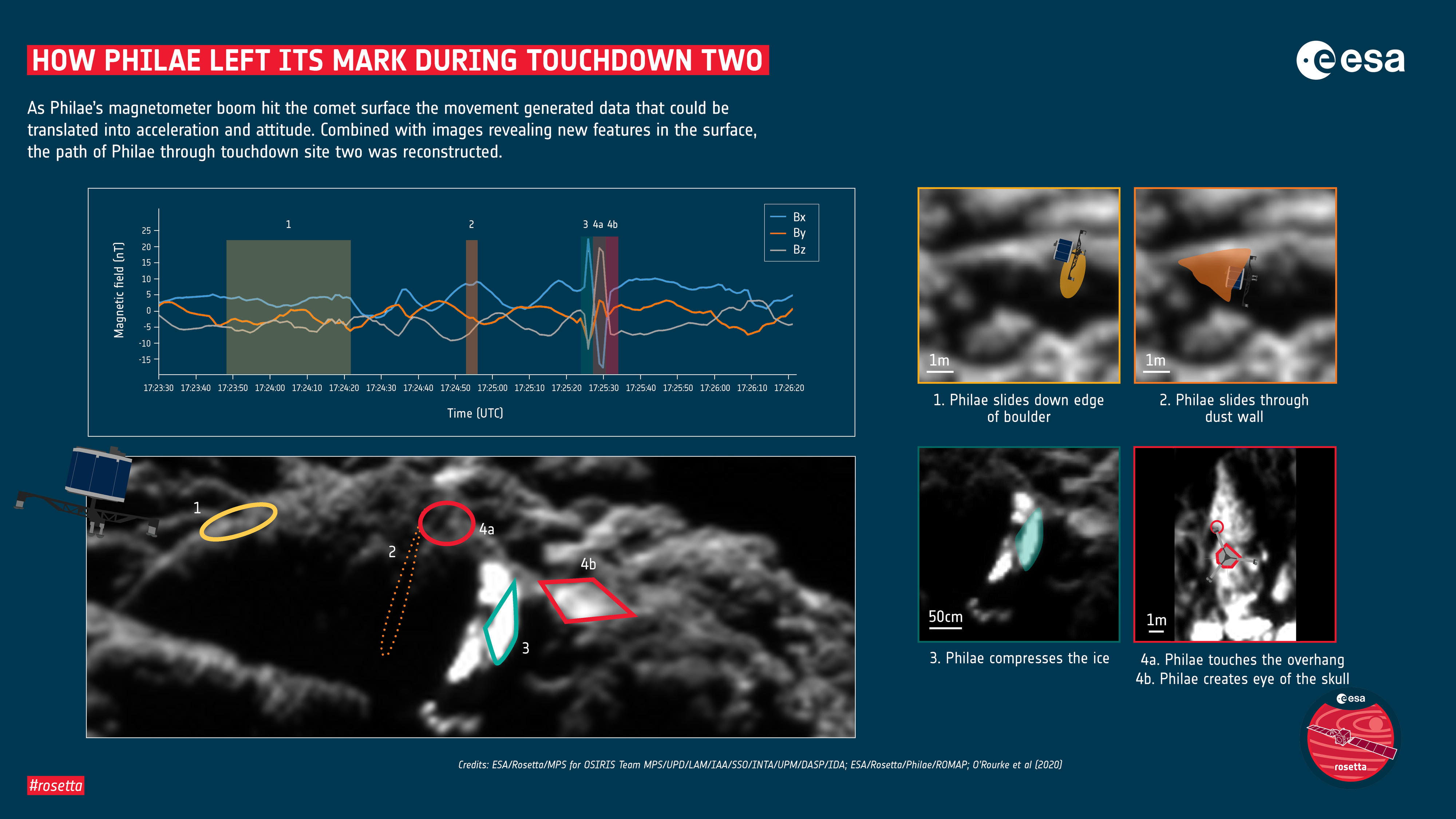

That mystery has now been solved, a new study reports. After analyzing reams of data gathered by the Rosetta orbiter and Philae — especially readings from the lander's magnetometer, which sits at the end of a 19-inch (48 centimeters) boom and registered every impact — a team led by O'Rourke has found the second touchdown site.

The spot lies just 100 feet (30 meters) from Philae's final resting place, the researchers report in the new study, which was published online today (Oct. 28) in the journal Nature. O'Rourke and his colleagues determined that Philae spent nearly two minutes at the second touchdown site, hitting the surface at least four different times in the process.

"The shape of the boulders impacted by Philae reminded me of a skull when viewed from above, so I decided to nickname the region 'skull-top ridge' and to continue that theme for other features observed," O'Rourke said. "The right 'eye' of the 'skull face' was made by Philae's top surface compressing the dust while the gap between the boulders is 'skull-top crevice,' where Philae acted like a windmill to pass between them."

These impacts unearthed bright material that the researchers determined to be water ice. The freshly excavated stuff looked quite different than the rest of Comet 67P's surface, which has been weathered by the harsh space environment, team members said.

And one of the impacts gouged a 10-inch-deep (25 centimeters) dent into a Comet 67P ice boulder — a scar that betrays a very soft body. Indeed, the researchers calculated that 67P's ice-dust interior is "fluffier than froth on a cappuccino, or the foam found in a bubble bath or on top of waves at the seashore," O'Rourke said.

Related: You can see every comet photo (and more) from Europe's Rosetta

The study team further calculated a porosity of 75% for that wounded boulder, meaning that it's three-quarters empty space. That figure is consistent with the porosity value for Comet 67P in its entirety, which mission team members determined in a previous study.

Neither Philae nor the Rosetta orbiter is still operational. The lander gave up the ghost early on, and mission team members guided its mothership (by then low on fuel) to a soft, controlled crash on Comet 67P's surface in September 2016. But the new results show that the historic mission, which launched all the way back in March 2004, continues to bear scientific fruit.

"This is a fantastic multi-instrument result that not only fills in the gaps in the story of Philae’s bouncy journey but also informs us about the nature of the comet," Matt Taylor, ESA's Rosetta project scientist, said in the same statement, referring to the new study.

"In particular, understanding the strength of a comet is critical for future lander missions," added Taylor, who was not involved in the newly published research. "That the comet has such a fluffy interior is really valuable information in terms of how to design the landing mechanisms, and also for the mechanical processes that might be needed to retrieve samples."

But designers of comet-sampling missions may be in for a real challenge, planetary scientist Erik Asphaug noted in a "News and Views" piece about the Philae results that was also published today in Nature.

Asphaug pointed out that Philae's planned touchdown site — the locale that hosted its first bounce — was a flat plain. Such regions, while (theoretically) easier to land on, are often covered by many meters of "lag" deposits, dust particles too hefty to be carried off by water vapor and other volatile gases that are boiled off when comets pass close to the sun, Asphaug wrote.

The plains therefore aren't likely to harbor easily accessible pristine material left over from the solar system's earliest days. Rather, Asphaug wrote, the new results "suggest that the best places to sample comets will not be the flat plains, but along the newly exposed ridges, cliffs and boulder piles, which are more difficult to land on."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.