'Farfarout' is officially the most distant object in our solar system

Farfarout now has an official designation: 2018 AG37.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It's official: Farfarout is our solar system's most distant known object.

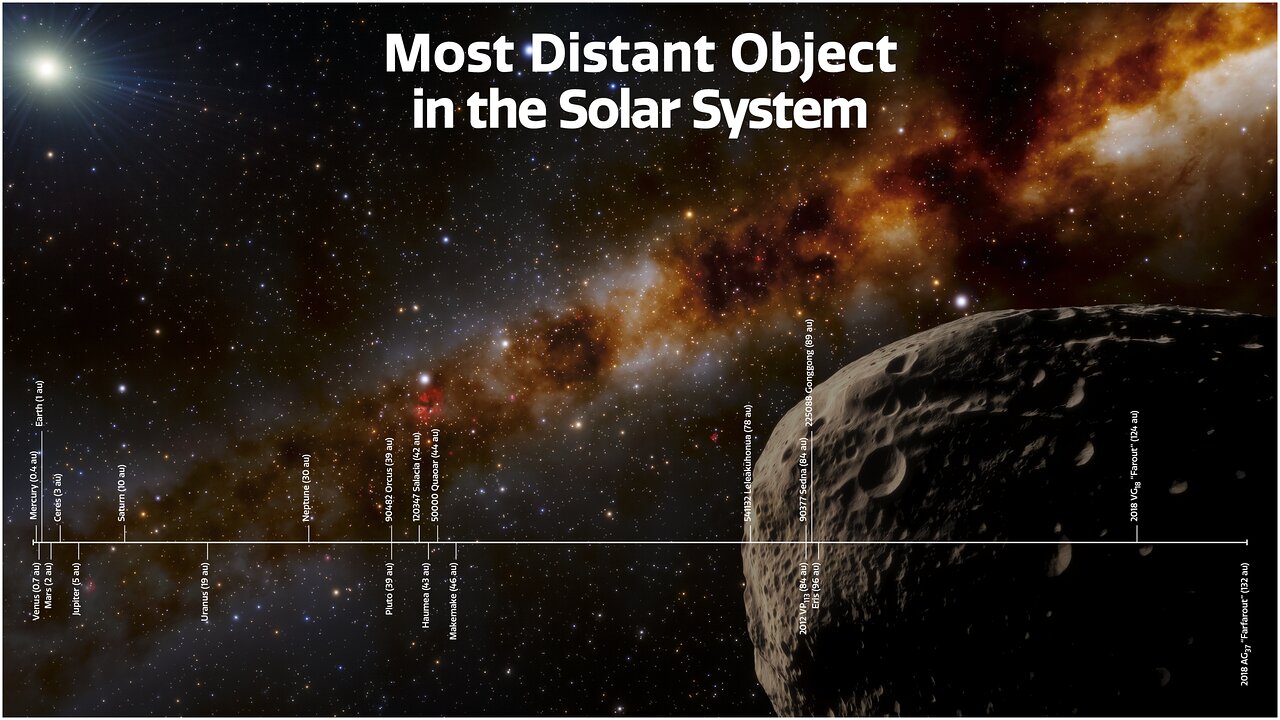

The planetoid dubbed Farfarout was first detected in 2018, at an estimated distance of 140 astronomical units (AU) from the sun — farther away than any object had ever been observed. (One AU is the average Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers. For perspective, Pluto orbits at an average distance of about 39 AU.)

Farfarout's inherent brightness suggests a world roughly 250 miles (400 kilometers) wide, barely enough to qualify for dwarf planet status. But the size estimate assumes the world is largely made of ice, and that assumption could change with more observations.

Article continues belowRelated: Solar system explained from the inside out (infographic)

Space.com Collection: $26.99 at Magazines Direct

Get ready to explore the wonders of our incredible universe! The "Space.com Collection" is packed with amazing astronomy, incredible discoveries and the latest missions from space agencies around the world. From distant galaxies to the planets, moons and asteroids of our own solar system, you’ll discover a wealth of facts about the cosmos, and learn about the new technologies, telescopes and rockets in development that will reveal even more of its secrets.

And speaking of more observations: The detection team has now collected enough additional data to confirm the existence of Farfarout and nail down its orbit. As a result, the planetoid just received an official designation from the Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which identifies, designates and computes orbits for small objects in the solar system.

That designation, announced Wednesday (Feb. 10) in a Minor Planet Center electronic circular, is 2018 AG37. (Farfarout will also receive a catchier official moniker down the road.)

"A single orbit of Farfarout around the sun takes a millennium," discovery team member David Tholen, an astronomer at the University of Hawai'i, said in a university statement. "Because of this long orbital period, it moves very slowly across the sky, requiring several years of observations to precisely determine its trajectory."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers spotted Farfarout using the Subaru 8-meter (26.2 feet) telescope on Maunakea in Hawai'i and traced its orbit using the Gemini North and Magellan telescopes.

"Only with the advancements in the last few years of large digital cameras on very large telescopes has it been possible to efficiently discover very distant objects like Farfarout," co-discoverer Scott Sheppard, a solar system small bodies scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science, said in the same university statement.

Farfarout is currently about 132 AU from the sun, the researchers determined. And its orbit is now known to be very elliptical, swinging between extremes of 27 AU and 175 AU, thanks to gravitational sculpting by Neptune.

"Farfarout was likely thrown into the outer solar system by getting too close to Neptune in the distant past. Farfarout will likely interact with Neptune again in the future, since their orbits still intersect," Chad Trujillo, an exoplanet astronomer at Northern Arizona University, said in a statement from the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab. (The laboratory's name reflects an acronym no longer used by NSF.)

Because Neptune plays such a large role in Farfarout's life, the planetoid likely cannot help astronomers in the hunt for Planet Nine, the big hypothetical world that some astronomers think lurks unseen in the far outer solar system.

Planet Nine's existence has been inferred from its putative gravitational influence on small bodies very far from the sun, whose orbits cluster in odd and interesting ways. But the small worlds that astronomers look to as bread crumbs in the Planet Nine search are free of Neptune's influence, unlike Farfarout, the researchers said.

The team that spotted Farfarout is well known for peering deep into the dark and frigid outer solar system. For example, in 2018, the researchers also found the distant object Farout and a faraway dwarf planet nicknamed "The Goblin."

And just to be clear: Farfarout's distance record refers to its current location. There are a number of other objects, such as the dwarf planet Sedna, whose orbits take them much farther away from the sun at points than Farfarout will ever get. And scientists think there are trillions of comets in our solar system's Oort Cloud, which begins about 5,000 AU from the sun.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.