China's Tiangong-2 Space Lab Falls to Earth Over South Pacific

HELSINKI — China carried out the controlled deorbiting of its Tiangong-2 space lab into the South Pacific, the China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO) announced Friday.

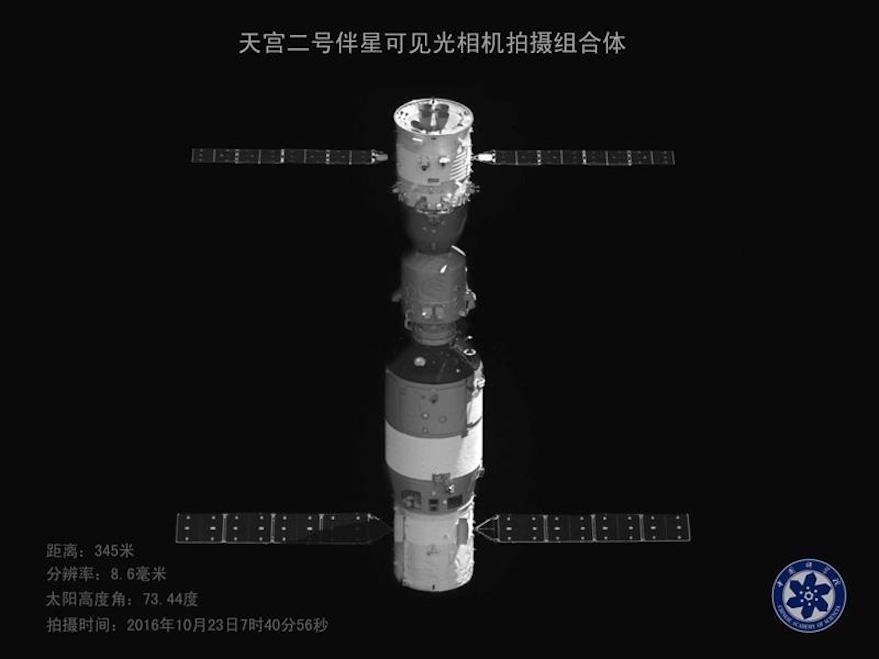

The 8.6-metric-ton Tiangong-2 ('Heavenly Palace 2') reentered over the South Pacific Ocean Uninhabited Area at 9:06 a.m. Eastern using its own propulsion, following an engine burn 10 a.m. July 18 to lower the spacecraft’s perigee. Limited onboard footage of the event was released shortly after.

CMSEO stated July 13 that it would end the Tiangong-2 mission July 19 Beijing time, in keeping with an announcement in September 2018 that the space lab would be deliberately deorbited this year.

Related: China's Tiangong-2 Space Lab in Pictures

The maneuver follows the high-profile and uncontrolled re-entry of Tiangong-1 in April 2018, having lost contact with and control of the experimental space lab in 2016.

Tiangong-2 was a more advanced version of the Tiangong-1 space lab which launched in 2011. Both were designed as stepping stones for developing and verifying technologies for larger 20-metric-ton modules for the planned Chinese Space Station (CSS), a long-term ambition laid out in 1992.

Tiangong-2 was launched in September 2016 to test advanced life support and refueling and resupply capabilities crucial to maintaining an inhabited space station in low Earth orbit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The 10.4-meter-long spacecraft hosted two astronauts, Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong, for the vast majority of the 33-day Shenzhou-11 mission in late 2016, which remains China's both latest and longest human spaceflight mission.

This was followed by the uncrewed Tianzhou-1 cargo mission, launched April 2017, which tested faster rendezvous and docking procedures, refueling in microgravity and further experiments.

Space station plans delayed

With the end of the Tiangong-2 China enters a period without a spacecraft capable of hosting human spaceflight missions for the first time since 2011.

China planned to launch the 'Tianhe' core module of the CSS in 2018, but the launch failure of second Long March 5 rocket in July 2017 has led to postponement of the test launch of the Long March 5B, a variant designed for carrying the space station modules into low Earth orbit.

An official with the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, the country’s main space contractor, told state-run Xinhua News Agency in January that a mission dress rehearsal involving a non-flight model of the rocket and the CSS core module would be carried out at Wenchang at the end of 2019. This would be part of preparations for the test flight of the Long March 5B which, if successful, would lead to the launch of the first CSS module in 2020.

However, the requisite return-to-flight of the Long March 5 — then slated for mid-July — appears to have slipped, with no indication from China as to when the launch will take place. The delay also means that the Chang’e-5 lunar sample return mission will almost certainly not take place in late 2019 as planned.

According to plans released by China, the 60-100-metric-ton Chinese Space Station will consist of a core module and two experiment modules. It is expected to be completed by ‘around 2022’ and will be capable of hosting three astronauts for long durations and up to six during crew turnover. It will be joined by a co-orbiting Hubble-class space telescope that can dock for propellant supply, maintenance and repairs.

In June six experiments were selected for a place aboard the future Chinese Space Station through a joint international cooperation initiative, with three more receiving conditional acceptance.

- Read SpaceNews for the Latest Space Industry News

- China's First Mars Spacecraft Undergoing Integration for 2020 Launch

- China Appears to Have Suffered a Long March Launch Failure

This story was provided by SpaceNews, dedicated to covering all aspects of the space industry.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.