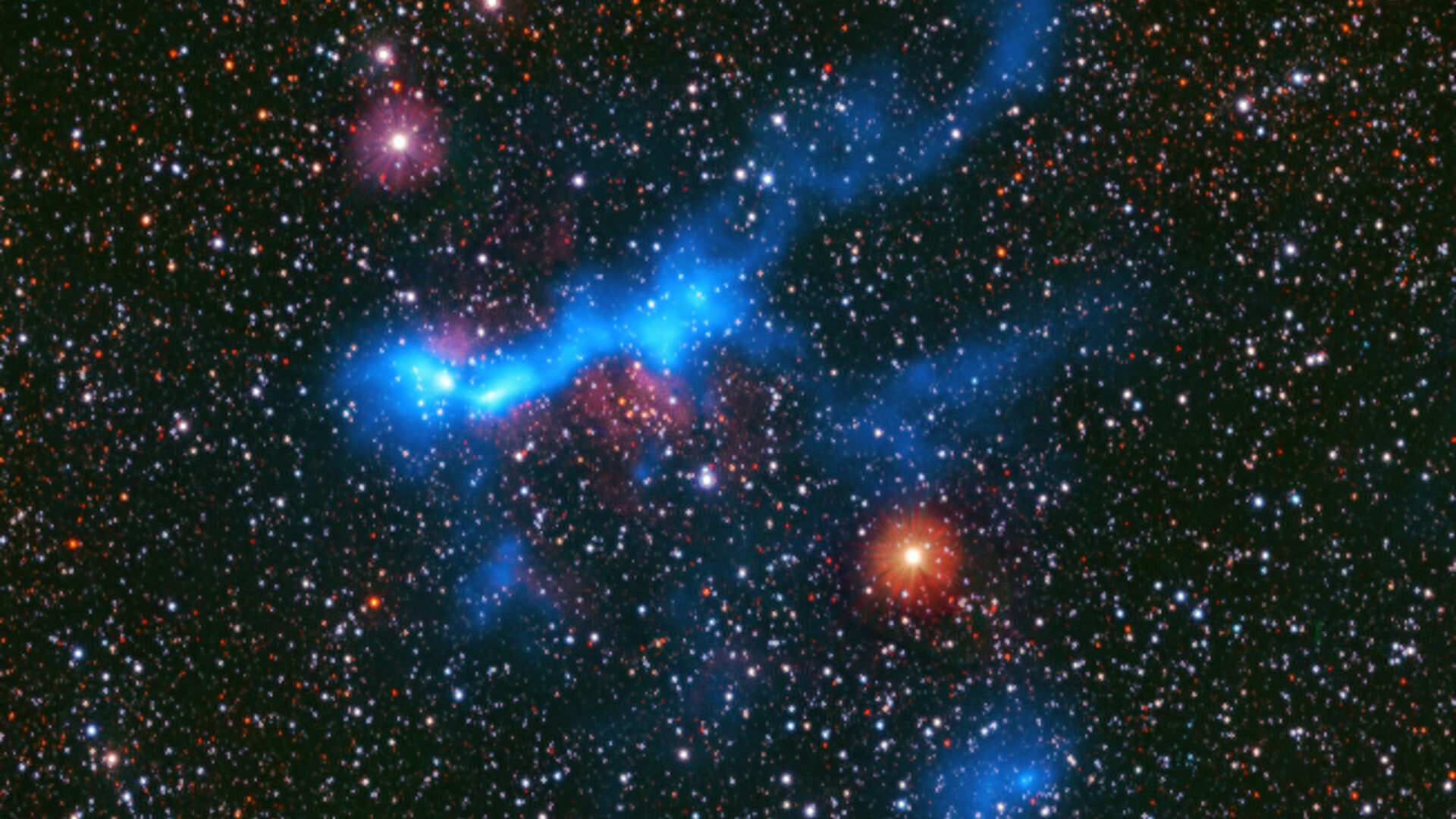

Searching for newborn stars with CAFFEINE | Space photo of the day for Jan. 22, 2026

The Core And Filament Formation/Evolution In Natal Environments (CAFFEINE) survey is an "astronomer's best friend," according to the European Southern Observatory.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

There are many questions surrounding the mechanics of star formation, from timeline to impact on surrounding stars. But for astronomers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), one particular question is of particular focus: If you pack more material into a star-forming cloud, do you get more stars for your trouble?

Using the ArTéMiS camera at the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) — a radio telescope in Chile operated by the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy — the ESO astronomers zoomed in on GAL316, a key stellar nursery. This image is part of a larger survey, the Core And Filament Formation/Evolution In Natal Environments (CAFFEINE) survey, which the astronomers are using to answer their key question — and fuel their thirst for knowledge.

What is it?

This is a layered, composite view of a stellar nursery that combines two perspectives on the same region of space. The blue, filamentary structure traces cold gas and dust — the raw ingredients of star formation — detected by APEX with the ArTéMiS camera. The background starfield comes from VISTA observations, showing the densely populated Milky Way region behind and around the cloud. Together, the two datasets make it easier to see how the invisible "fuel" for future stars threads through a field already full of older ones.

Where is it?

GAL316 is a star-forming region in our Milky Way.

Why is it amazing?

CAFFEINE was designed to test whether the densest star-forming regions become more productive, converting a higher fraction of their material into new stars once they pass the minimum density needed for star birth. The survey's results suggest the opposite of the intuitive guess: above that threshold, the densest regions observed didn't seem any more efficient at forming stars than other nurseries.

That matters because it hints that star formation isn't limited by "not enough stuff" once clouds reach a certain point. Instead, other brakes may still be at work even in the richest regions, the internal motions of the cloud, the way material fragments, and the early influence of young stars on their surroundings. In other words, piling on more gas and dust doesn't automatically turn a stellar nursery into a star-making machine.

Want to learn more?

You can learn more about stellar nurseries and the European Southern Observatory.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.