How the Red Planet craze started 120 years ago: Interview with 'The Martians' author David Baron

"What is it about Mars that has made it so prominent in our culture, almost more than any other celestial object?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

At the turn of the 20th century, the "Mars Craze" reached a fever pitch, fueled by tales of intelligent canal-building Martians and the tantalizing possibly of contact between planets. Newspapers breathlessly reported on sightings and speculations, blurring the line between science and sensationalism.

Today, this fascination endures — only now it's bolstered by rovers, orbiters, and plans for possible colonization.

Author and science writer David Baron knows this allure well. In his new book, "The Martians," which will be released on Aug. 26, 2025, he dives into the history of that early Mars mania, uncovering a story as much about human imagination as about astronomy.

Over the seven years Baron took to research and write this book, he traced the mythos of Mars through newspaper archives, personal letters and diary entries and visits to legendary observatories from Arizona to the Atacama to Italy.

Space.com caught up with Baron about the behind-the-scenes work that went into "The Martians." From new names to beloved characters like Nikola Tesla, Baron dives into the scientists and eccentrics who shaped Mars' legendary status and why our planetary neighbor continues to be a vessel for our biggest hopes to this day.

Space.com: What got you interested in writing this book?

David Baron: This is my third book, and my previous book "American Eclipse," which came out in 2017, was about the history of astronomy — specifically, the story of a total solar eclipse that crossed America's Wild West in 1878. I was a journalist for many years, and while I didn't consider myself a historian, I really enjoyed the process of digging up history and bringing it to life. And so I thought it would be fun to do another book on history of science — ideally, history of astronomy.

I remembered from my childhood being fascinated by Martians and being surrounded by Martians ... It just got me wondering, what is it about Mars that has made it so prominent in our culture, almost more than any other celestial object? It has this real sense of mystery and romance.

As soon as I started to look at newspapers from the turn of the last century, my jaw just dropped. I mean, to read in "The New York Times" in 1906, in all seriousness, about the Martian civilization and what we might learn from them and attempts to communicate with them. The idea that Martians were thought to be scientific fact before they were staples of science fiction — I thought, well, there's got to be a good story here.

Space.com: You bring us on this journey throughout this book of going through all these old papers and journals and diaries. What was that research process like?

David Baron: It's like some great treasure hunt where you find a nugget, which is such a thrill, but you have to go through so much waste rock to get to that nugget. It's a very laborious, time-consuming project. And you really have to be a masochist, I think, to take on a project like this.

With this book, I didn't want to just repeat what people have said before. I wanted to say something new. And that meant finding new information, things that hadn't been seen since they were published in the 19th century, or maybe even things that have never been seen that are hidden in some archival collection.

I collected many thousands of newspaper articles about the Martians during that time. And I went through thousands of original letters between and among my various characters.

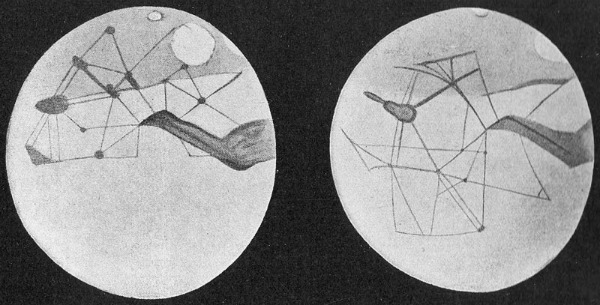

It was fun to actually visit some of the important places that figure in the book, like the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, where I got to look through Percival Lowell's very telescope that he used to spot the canals on Mars. I also visited the Brera Astronomical Observatory in Milan, where Giovanni Schiaparelli first spied the canals on Mars. But the most exotic trip was going to the Atacama Desert in the absolute middle of nowhere in Chile, to the place where the Mars craze really reached its climax. This was when this 7-ton telescope was transported down to the Chilean desert to take 10,000 photographs of Mars that supposedly proved that the canals were real.

With this book, I didn't want to just repeat what people have said before. I wanted to say something new. And that meant finding new information, things that hadn't been seen since they were published in the 19th century, or maybe even things that have never been seen that are hidden in some archival collection.

Space.com: Why did you pick 'The Martians' as the title?

David Baron: I had more than 100 possible titles, but that just seemed like the right one. And I really originally meant it as the scientists who believed in the existence of Martians. Lowell called himself a Martian, and the Martian ambassador.

But it works both ways, obviously. It is ultimately about the Martians of Mars and the Martians of Earth.

Space.com: Did you see parallels between the hype of Mars at the beginning of the 20th century and the enthusiasm we see today?

David Baron: Absolutely. I mean, if I'm going to write a book about history, I want to make sure that it resonates with what is happening today. There has be some reason people will care about this story that happened more than 100 years ago.

I felt it resonated in a couple of ways. Firstly, there's still a passion for Mars. We're looking for life on the planet right now. That life is not going to be canal-building intelligent beings, but there may be microbes up there. But more importantly, there is serious talk of certainly sending astronauts to Mars and but also possibly colonizing Mars.

Secondly, the other way I think this book resonates, which I don't make explicit, is because of all the excitement about exoplanets. The scientific community is actively looking for habitable, maybe inhabited planets. You know, there are more than 5,500 exoplanets that have now been found, and a number of them seem to be at least theoretically habitable. Right? So, we could see the same kind of craze about that that we saw for the Mars craze at the turn of the last century.

Another thing I highlight in this book is that I see the Mars craze both as a cautionary tale and an inspiring tale. It's a cautionary tale because we have a tendency to see things that we want to see and convince ourselves that things are true when they're not, because we so want them to be true. And I think that's true today.

I'm very excited by Mars science and Elon Musk's ideas. I think they're very far out there, and I think the reality of getting to Mars and living on Mars is going be so much harder than we can possibly imagine. But at the same time, I do think ultimately it's humanity's future, and I'm very excited by it. But when you see what some of the zealots say about why we should go, they portray the future of humanity on Mars as this kind of techno-utopia. We're going to leave the Earth behind, and the selfishness of Earth behind, and create a better society. And it's a wonderful vision, but I wonder if it's realistic. So that's why this is a cautionary tale.

It's also an inspiring tale, because there's a direct connection between the excitement of Mars back then and the science today. Einstein said it the best: "Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research."

You need to be able to imagine things to then go pursue what the truth is. And Percival Lowell had a very good imagination. I think it was very helpful for a while. His theory of the Martian canals in the 1890s was not crazy; it was an interesting hypothesis worthy of study. But he got carried away with his imagination. He couldn't back down when the evidence ran counter to it.

But imagination is important for inspiring us. If you want to launch a space mission, it takes a lot more than rocket fuel and carbon fiber and metal. So Lowell lit this fire of imagination which has ripples all the way through the 20th century to today. So, as I write about in my book, Carl Sagan made it clear that he became astronomer because of the Mars fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs, which came directly out of Percival Lowell's work. Similarly, Robert H. Goddard became a rocket scientist because he was infatuated by "The War of the Worlds," written by H.G. Wells.

Space.com: Final question — Did you originally plan to have Tesla in the book?

David Baron: Yes. Pretty early on, I knew that I wanted to add him, because in 1899 he thought that he picked up radio signals from Mars, and that just propelled the Mars excitement to new levels of craziness. So I knew he was gonna be in the book somewhere.

But then came the challenge of having all of these characters and figuring out how to weave them together. But he was definitely was an important character.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.