Tracing the Canals of Mars: An Astronomer's Obsession

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In a remarkable discovery, images taken over the past five years by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which circles Mars to photograph the planet, seem to indicate the presence of liquid water there.

For decades, space scientists had searched the Red Planet without detecting the life-sustaining liquid, and concluded that it was bone-dry.

This past August, however, scientists found dozens of slopes across the southern hemisphere of Mars where previously undetected dark streaks come and go with the seasons. When the planet heats up, the streaks appear and expand downhill; they disappear when it gets cold. Scientists think it may be evidence of melted, salty water running down slopes during the Martian summer.

Five image sequences from the Newton crater and one from the Horowitz crater show the black lines appearing near the tops of slopes and then growing into scores of streaks that remain for months until the cold weather returns and they disappear. At Newton Crater, photos indicate as many as 1,000 of these possible streams flowing down the slopes and into a basin. [Photos: The 'Face on Mars' and Other Mars Illusions]

If confirmed, the discovery would fundamentally change our understanding of Mars, lending support to the theory that the planet was once far more wet and warm, and would renew hope that it may be able to support life.

About 120 years ago, however, at least one prominent astronomer was convinced that Mars not only supported life, but was home to an advanced civilization. Martians, the theory went, had built an extensive network of canals to draw water down from supposed icecaps at the Red Planet’s poles to irrigate a world that was drying out.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The man who 'discovered civilization' on Mars

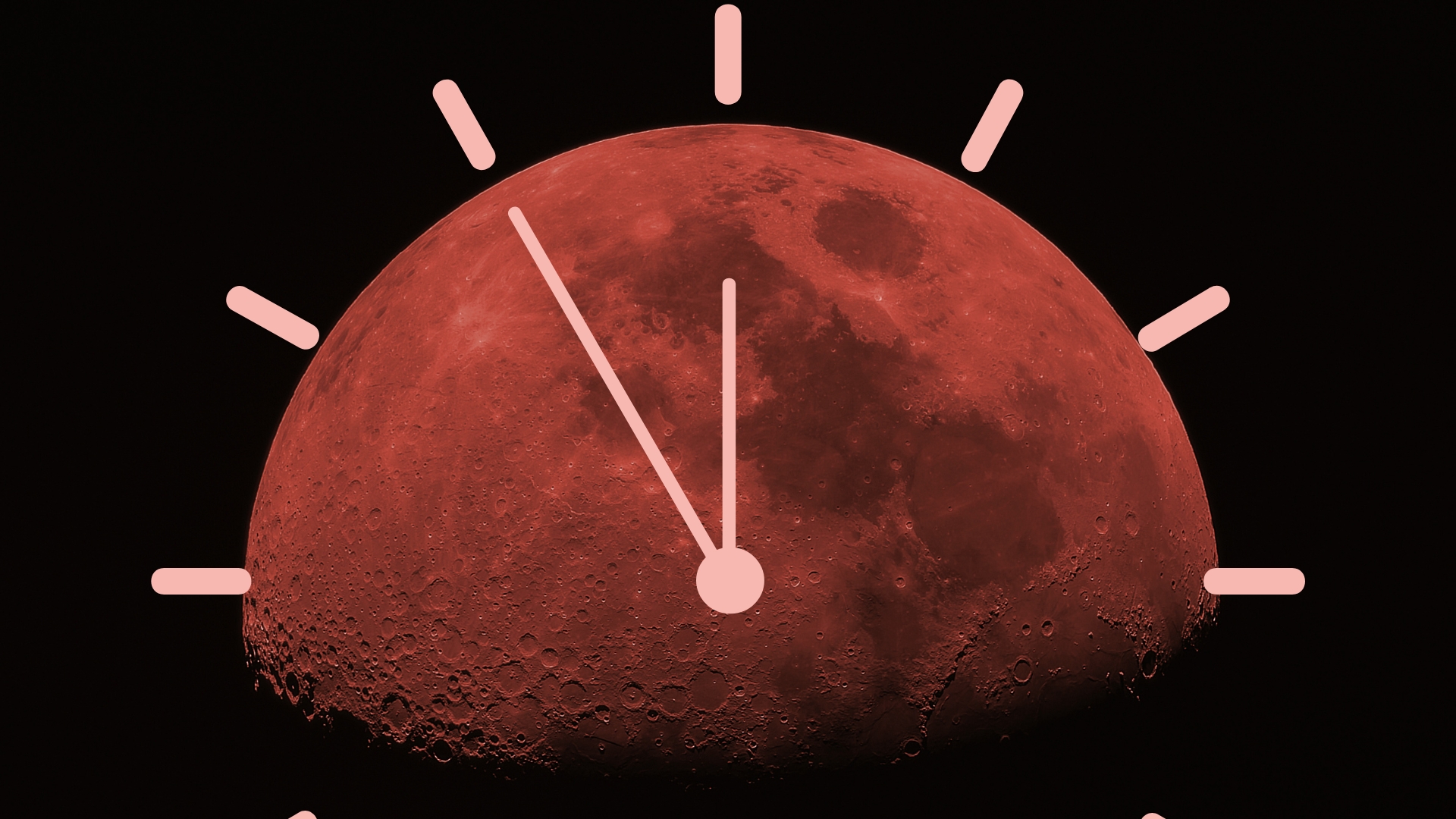

These immense illusory earthworks (Marsworks?) had been studied in detail by one of the greatest astronomers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the wealthy and socially prominent Percival Lowell.

In his day, Lowell was far and away the most influential popularizer of planetary science in America. His widely read books included "Mars" (1895), "Mars and Its Canals" (1906), and "Mars As the Abode of Life" (1908).

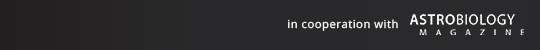

Lowell was not the first to believe he saw vast canals on Mars. That distinction belongs to the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who in 1877 reported the appearance of certain long, thin lines he called canali, meaning channels in Italian. But he stopped short of attributing them to the work of intelligent Martians. (“Leave the Martians; take the canali.”)

Lowell carried the matter much further. Captivated by these sketchily observed — and ultimately nonexistent — phenomena, Lowell spent many years attempting to elucidate and theorize about them. The lines, he thought, must “run for thousands of miles in an unswerving direction, as far relatively as from London to Bombay, and as far actually as from Boston to San Francisco.”

He thought the Red Planet must once have been covered by lush greenery, but was now desiccated; the "canals" were an admirable attempt by intelligent and cooperative beings to save their home planet. [5 Bold Claims of Alien Life]

The Canals of Mars became one of the most intense and wrongheaded obsessions in the history of science, capturing the popular imagination through dozens of newspaper and magazine articles, as well as such classic science fiction as "The Princess of Mars," a pulp classic by Edgar Rice Burroughs, who also created the immortal "Tarzan of the Apes." (Burroughs had a rare gift for knowing what the public would adore, from Ape-Men to Little Green Men.)

Despite the fact that his "canals" and elaborate descriptions of Martian civilization turned out to be the product of self-delusion (though not a deliberate hoax), Lowell’s name remains honored in the annals of astronomy.

Lowell's astronomy legacy

To pursue his misguided obsession, Lowell founded and funded one of the world's great observatories on a 7,200-foot (2,195-meter) mountain peak he named Mars Hill, near Flagstaff, Arizona. There he scrutinized the heavens, and particularly Mars, with, his own custom-built 24-inch refracting telescope, built in 1894, which became a marvel of the age.

In 1930, American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered the dwarf planet Pluto using a telescope at the observatory.

In 2012, the Lowell Observatory, which now hosts 80,000 visitors a year, will complete its 4.3-meter Discovery Channel Telescope. That state-of-the art instrument will vastly expand the breadth of the observatory's research capabilities and bring new images of the universe to hundreds of millions through direct television transmissions.

And if Earth is not invaded by Martians or pummeled by giant asteroids within the coming week, my next story will reveal how Lowell’s beloved Martian inhabitants were shot down by another remarkable scientist: none other than Charles Darwin’s junior partner in evolutionary theory, Alfred Russel Wallace.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program.