What is the temperature on the moon?

The temperature on the moon can vary drastically between lunar day and night time.

The temperature on the moon can reach a blistering 250° Fahrenheit (120° Celsius or 400 Kelvin) during lunar daytime at the moon's equator, and plummet to -208 degrees F (-130° C, 140 K) at night.

In certain spots near the moon's poles temperatures can drop even further, reaching - 424° F (- 253°C or 20 K) according to NASA.

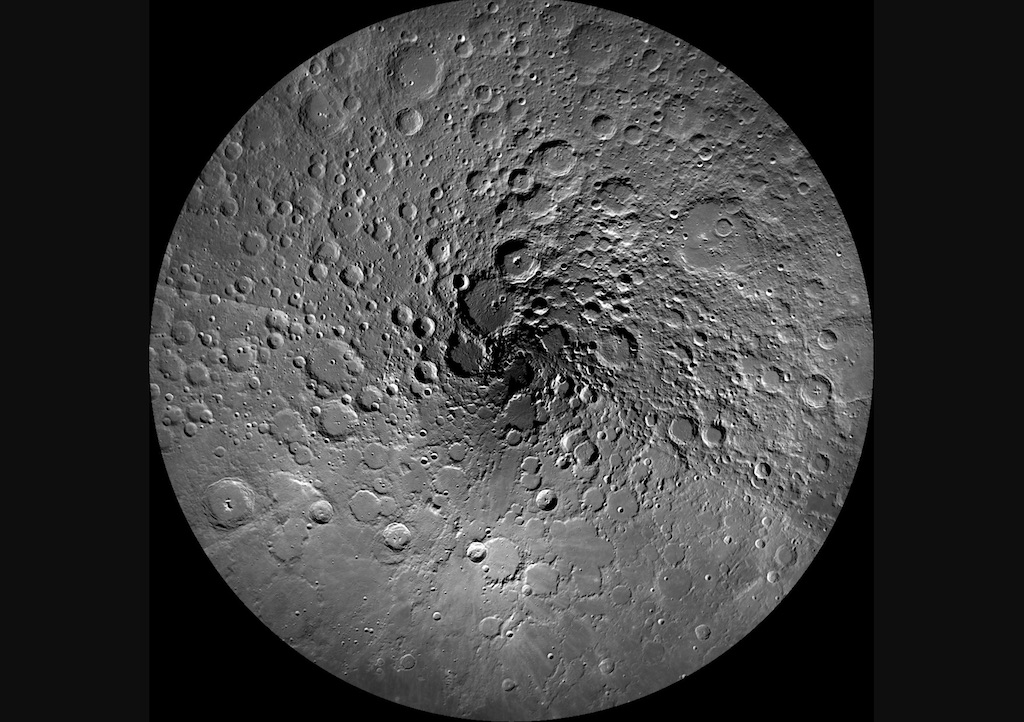

One reason for these dramatic extremes is that the moon has no lunar atmosphere to insulate heat. Its lack of a gaseous blanket also means that craters and major dramatic landmarks do not erode the way they do on Earth, leaving perpetual pockets of darkness near the moon's poles that host the moon's most frigid temperatures.

Related: How far is the moon from Earth?

Lunar daytime is roughly two Earth weeks long since the moon takes a little less than one month — about 27.3 days — to complete one of its days, according to a study published in August 2019 by the Journal of Geophysical Research. Lunar night time is also about two weeks long.

Measuring the temperature on the moon

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) provides the best knowledge about the moon's temperature. The mission launched in 2009 and one instrument in particular — the Diviner Lunar Radiometer — has been crucial to understanding the lunar climate.

Knowing the moon's temperature at any given spot has different benefits. For instance, astronomers hoping to better understand its topography can glean a lot about the number of rocks present across the moon's different regions by knowing an area's temperature. This is because lunar rocks take longer to heat up and cool down than lunar soil, or regolith, which allows scientists to identify especially-rocky areas, according to NASA. This happens after other factors that influence lunar temperature are factored out of the equation, such as latitude and elevation.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Moon viewing guide — What to look for on the lunar surface

Latitude plays an important role because the moon's axis is oriented in such a way that sunlight just grazes over the lunar poles. The lunar topography at the poles is populated by non-eroding craters and crevices that produce permanently shadowed regions (PSRs). The lack of sunlight promotes exceptionally frigid temperatures here.

Why do we need to know the temperature?

This brings up another big reason why the moon's temperature is interesting to researchers: the ambitious reactivation of crewed moon missions through NASA's Artemis Program.

The idea is to return astronauts to the lunar surface and to develop an ongoing presence there. Rather than short visits, current concepts for Artemis missions are leaning more towards models where astronauts would spend more time on the moon than they did during the Apollo program. This would be supported by an outpost on or in orbit around the moon. For this reason, NASA and other space agencies have been curious about where the resources to supply these longer-duration missions could come from, and one idea is to use lunar ice for fuel or even drinking water. NASA's upcoming Volatiles Investigation Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) mission will help the agency assess those possibilities.

"PSRs often possess temperatures low enough to cold-trap water ice," according to the Journal of Geophysical Research. Researchers also noted that temperatures are cold enough at the poles that water remains frozen over billions of years. Even at these long time scales the ice goes through very little sublimation, or the process by which water turns from ice into vapor without first melting.

There is still a lot left to learn about the lunar environment, and a comprehensive picture of lunar temperature will require more years of research, according to the study's authors. That's because LRO's Diviner instrument "does not continuously sample all local times at all seasons, but rather obtains data from high-resolution orbit tracks that migrate around the poles."

That said, LRO has already amassed more than a decade's worth of data that gives researchers a strong start at grasping the peculiarities of the moon's temperature.

Additional resources

For the latest news about NASA's LRO mission, visit the space agency's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter page. Also, check out the Artemis Program portal on the NASA website for more information about the next venture to the moon.

Bibliography

"Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: Temperature Variation on the Moon." National Aeronautics and Space Administration, May 14 2014. https://lunar.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/lithos/LROlitho7temperaturevariation27May2014.pdf

J.P. Williams et al. "Seasonal Polar Temperatures on the Moon." Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets (2019). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2019JE006028