UK Takes Aim at Commercial Spaceflight, Spaceport Possible by 2018

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The United Kingdom could have a spaceport by 2018.

Pending a regulatory report to be published this July and a technical feasibility study that is underway with the country's National Space Technology Programme (NSTP), it is possible that the country could host a spaceport within the next five years. A new National Space Flight Coordination Group, chaired by the U.K. Space Agency, will oversee these reports and the future work for this U.K. spaceport. Government officials hope this will be the start of commercial spaceflight for the country.

The group and the 2018 date were announced with the publication of the "Government Response to the U.K. Space Innovation and Growth Strategy 2014-2030," published last November by industry. This publication set out how the country's space sector could be worth 40 billion pounds ($67 billion) by 2030. The industry is worth 9 billion pounds ($15 billion) today. [Private Spaceflight: Latest Launches and News]

"This [National Space Flight Coordination] group reports to [government] ministers," the government's response says. "Its cross-cutting nature is recognition of the scale of the challenge inherent in identifying, approving and building a U.K. spaceport and in supporting all the necessary innovation and technology that it would require."

These are not the first reports and studies the U.K. government has undertaken for a spaceport, but it is the first time the government has set a date for the creation of such a facility. In 2009, the British National Space Centre (BNSC), which preceded the U.K. Space Agency created in 2010, funded a study into spaceport candidate locations. That study concluded that Lossiemouth in Scotland would be the best site.

Located in northern Scotland, Lossiemouth is on the coast of the North Sea and has a Royal Air Force base with a runway suitable for the types of launch systems that Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Galactic uses. That company had already identified Lossiemouth as a possible U.K. spaceport; in 2009, then Virgin Galactic President Will Whitehorn, who was born in Scotland, spoke of his hope for a spaceport in the location.

A September referendum on whether Scotland will remain a part of the United Kingdom could complicate that choice, however. (The United Kingdom currently consists of Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland.) If the yes vote in the referendum wins, Scotland could be an independent country by 2018.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In addition to selecting a spaceport site, the U.K. government's Science and Technology facilities Council (STFC) produced a report in 2008 for the BNSC about how launches including manned flights could be regulated.

That STFC report recommended something similar to the Federal Aviation Administration's phased approach, which matches the industry's development and facilitates it. The report added that BNSC should seek an international framework and identify mutual recognition agreement opportunities for launch licensing.

However, new regulations may be needed long before 2018, because Virgin Galactic is a U.K. company. Under the Outer Space Treaty that the United Kingdom signed, governments are responsible for launches by their citizens. While a U.S.-registered company, Virgin Galactic LLC, will conduct the commercial launches expected to start later this year, Branson's ownership of that firm could require U.K. government licensing.

It is probably because of this that the National Space Flight Coordination Group's work will, according to the government's response, move forward with space plane regulation.

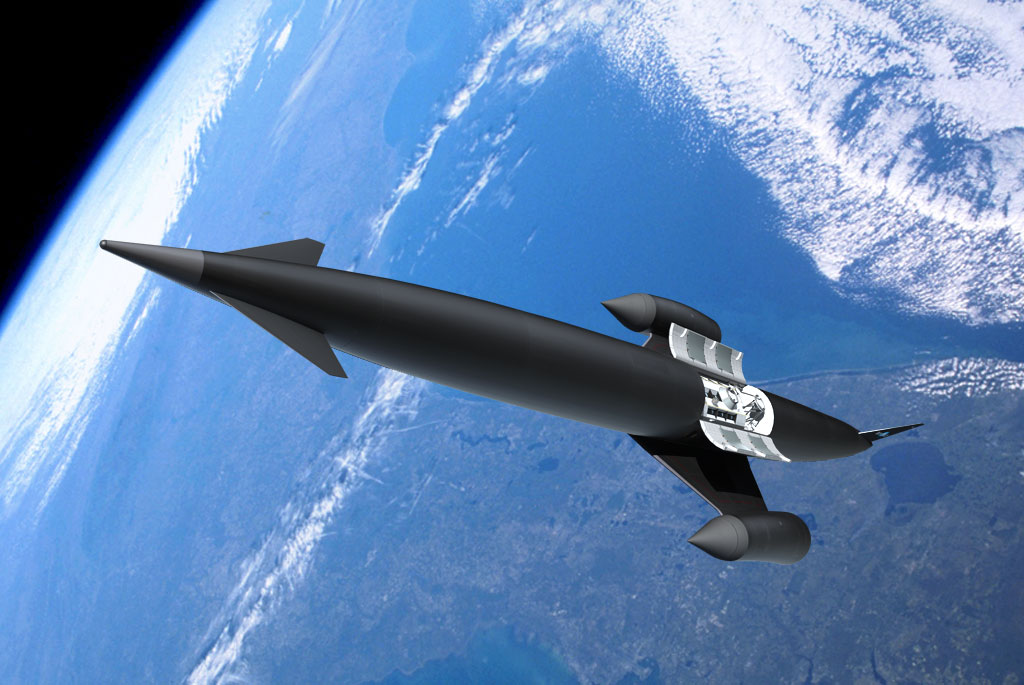

The group will also examine investments in space planes. In July 2013, the U.K. government announced it would provide 60 million pounds ($100 million) over two financial years, 2014-2016, to be matched with private financing for engine development for Reaction Engines' Skylon space plane.

The NSTP, which is producing a technical feasibility study for the 2018 spaceport, will also conduct 10 "reviews of game-changing technologies," according to the government's response. To encourage technology development, the NSTP is considering offering prizes. [See photos of the Skylon space plane]

Another funding mechanism the agency says it wants to develop is a "repayable investment funding mechanism similar in principle to the civil aviation 'Repayable Launch Investment." This scheme supports business applications and services, payloads, and "innovative platform[s]." That may include support for Virgin Galactic's unmanned air-launched rocket,LauncherOne, which would deliver micro satellites into orbit.

Other recommendations in the government's response include increasing NSTP funding, reducing fees and red tape so new space companies have fewer obstacles, increasing the number of U.K. people in senior positions at the European Space Agency (ESA) — to promote the use of private-public partnerships in ESA programs, ensuring the U.K. makes the most of opportunities under the European Union’s 12 billion euro ($16 billion) 2014-2020 space research funding, and increasing bilateral science projects with other nations. The government will also set up a satellite signal spectrum group.

Along with the industry strategy response, the government published its National Space Security Policy. This follows the U.K. Space Agency's Civil Space Strategy 2012-2016. The goals of the National Space Security Policy, which makes no reference to funding, are to make the United Kingdom more "more resilient to the risk of disruption to space services and capabilities," enhance the country's "national security interests" and promote a "more secure space environment." The strategy also aims to help industry and academia to "grasp commercial opportunities" in national space security.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Rob Coppinger is a veteran aerospace writer whose work has appeared in Flight International, on the BBC, in The Engineer, Live Science, the Aviation Week Network and other publications. He has covered a wide range of subjects from aviation and aerospace technology to space exploration, information technology and engineering. In September 2021, Rob became the editor of SpaceFlight Magazine, a publication by the British Interplanetary Society. He is based in France. You can follow Rob's latest space project via Twitter.