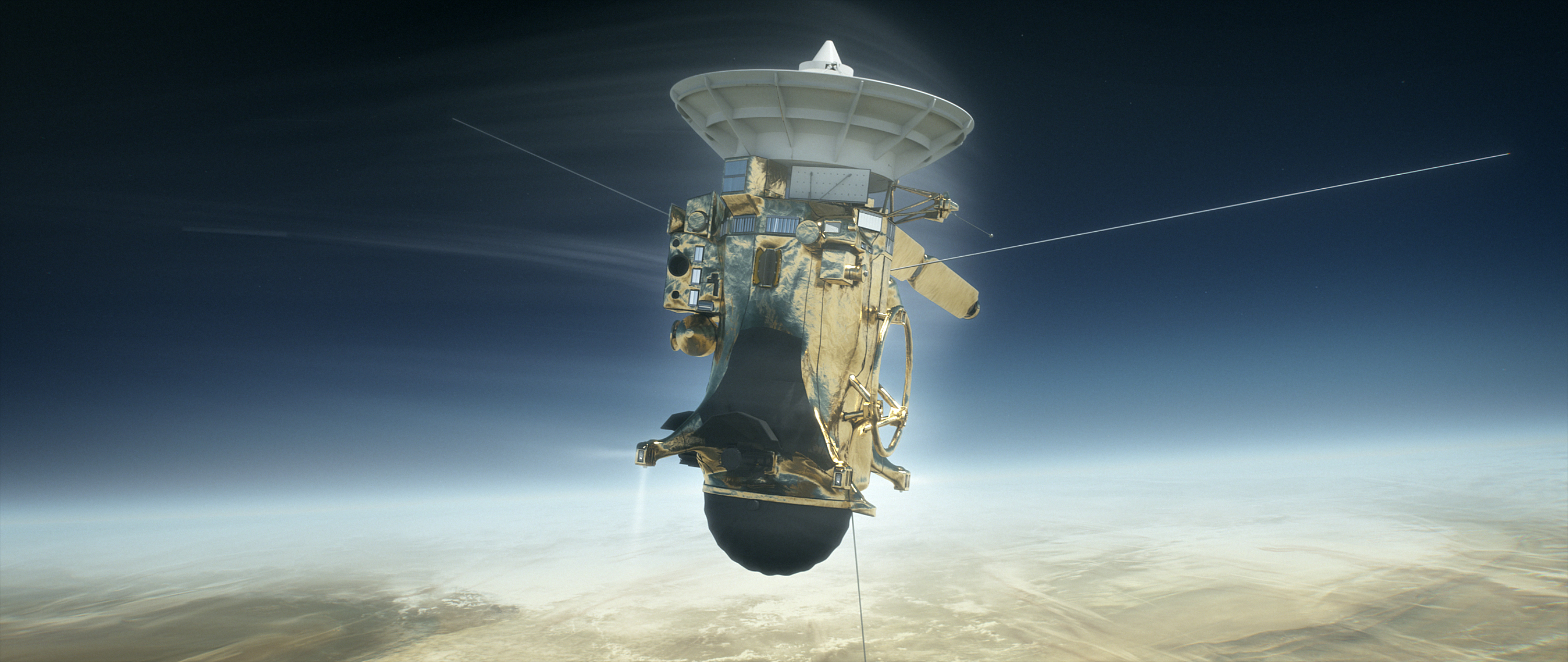

Epic Cassini Saturn Mission Begins 'Grand Finale' This Month

PASADENA, Calif. — NASA's veteran Cassini mission will officially kick off its farewell tour of the Saturn system on April 22 with a final close encounter of the ringed planet's largest moon, Titan. Five months later, on Sept. 15, Cassini will spectacularly burn up in Saturn's crushing atmosphere.

But before that happens, Cassini will dive through a 1,200-mile (1,930 kilometers) gap between the planet and its innermost ring to carry out science that is only possible now that the mission is running out of fuel.

"What a spectacular end to a spectacular mission," Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C., said via video link at a special news conference held here today (April 4) at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). [Cassini's 'Grand Finale' at Saturn: NASA's Plan in Pictures]

The "Grand Finale" will begin when Titan's gravity hurls the spacecraft close to Saturn's atmosphere, ending the probe's series of ring-grazing orbits and causing Cassini to dive through a gap in the rings.

Over the next 22 orbits between the planet and the innermost ring, Cassini will embark on a completely different phase of discovery. The spacecraft will carry out scientific measurements of the apparently empty environment between the planet's upper-atmosphere gases and the innermost edge of Saturn's D-ring.

"The Grand Finale is a brand-new mission," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL. "We're going to a place that we've never been before … and I think some of the biggest discoveries may come from these final orbits."

This unique trajectory will allow Cassini to make incredibly detailed maps of Saturn's magnetic and gravitational fields, helping scientists understand what structures lie beneath the planet's atmosphere and, potentially, revealing the mechanisms behind Saturn's mysterious spin. This is also the best opportunity yet to get a good look at the mysterious hexagon etched into the clouds around Saturn's north pole, mission team members said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Since arriving in Saturn orbit in 2004, Cassini has steered clear of the planet's icy ring material, opting for a more distant (and safer) orbit where the gas giant's family of moons could be studied and Saturn could be observed from afar. But now that the mission is in its final months, more risks can be taken to carry out observations that scientists would have only dreamed of earlier in the mission.

During the daring ring dives, Cassini will be closer to the planet than ever before. The probe will use its mass spectrometer to "taste" the chemistry of the tenuous gases on the outermost edge of Saturn's atmosphere and return the most detailed observations ever obtained of Saturn's high-altitude clouds and ring material. [Latest Saturn Photos by Cassini]

Mission team members are taking pains to minimize the dangers associated with this privileged view.

"We don't know exactly where that D-ring ends … so, to be on the safe side, we want to protect the spacecraft's instrumentation from these particles," Spilker said. After all, Cassini will be on a "ballistic trajectory," traveling at a speed of 76,000 mph (122,000 km/h).

"It's going to be kind of risky," Green said. "The ring material actually falls into Saturn, and it won't take much to stop our spacecraft at the velocity it is flying."

Although models of Saturn's rings suggest the inner gap will be mainly empty, mission scientists said they assume some small particles will hit Cassini. So, as the spacecraft makes its ring-plane crossings, it will be oriented in such a way to maximize the shielding of delicate instrumentation behind Cassini's high-gain antenna.

"We expect a lot of impacts, but it will be like going through smoke … we believe the D-ring extends into Saturn," Cassini program manager Earl Maize, also of JPL, told Space.com. He added that mission team members are confident that Cassini will encounter only the smallest particles in the ring gap, and the probability of losing the spacecraft to an impact with something bigger is "less than 1 percent."

Cassini's Grand Finale is occurring this year because the spacecraft has been so active and so prolific, Maize added.

"Back in 2010, we decided that we'd use every last kilogram of propellant to explore the Saturn system as thoroughly as we could," he said. "We'll end up with no gas in the tank, but at the same time, this is a very serious constraint. Ultimately, Cassini's discoveries (caused) its demise."

But why crash Cassini into Saturn? NASA decided to incinerate the probe to ensure that it doesn't careen into, and potentially contaminate, Titan or the fellow Saturn moon Enceladus, both of which may be capable of supporting life. (Cassini was sterilized before its October 1997 launch, but some microbes from Earth may still survive aboard the probe, agency officials have said.)

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency — has made a number of mind-blowing discoveries during its time in the Saturn system.

For example, Cassini spotted liquid-hydrocarbon seas on Titan, making the moon the only place beyond Earth known to harbor bodies of stable liquid on its surface. (And the mission's piggyback lander, called Huygens, touched down on Titan in January 2005, becoming the first probe ever to land on a body in the outer solar system.)

Cassini also discovered Enceladus' amazing water plumes, which in turn helped reveal that the satellite hosts an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy shell. And the probe has imaged Saturn's diverse family of moons in detail that was not possible before.

In addition, the mission has studied the dynamics of Saturn's rings extensively, revealing the intricate relationships among planet, rings and moons. Saturn's unique environment has acted like a natural laboratory, demonstrating how moons are formed and destroyed — findings that can be scaled up to better understand how planets formed around the sun and, perhaps, around other stars, scientists have said. In short, the data gathered by the spacecraft will keep researchers busy for decades to come, scientists said.

Cassini has been a decades-long odyssey for the scientists involved, and the probe's 3-minute final dive into Saturn's atmosphere on Sept. 15 will be a bittersweet moment, the researchers said.

"I think that once the signal is lost, it would mean the heartbeat of Cassini is gone," said Spilker. "I think there will be a tremendous cheer and applause for the completion of an absolutely incredible mission. Hugs, tears — the Kleenex box will be passed around — but we will rejoice at being part of such a wonderful mission."

Follow Ian @astroengine and www.astroengine.com. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.