One Last Year at Saturn: Cassini Heads for Grand Finale

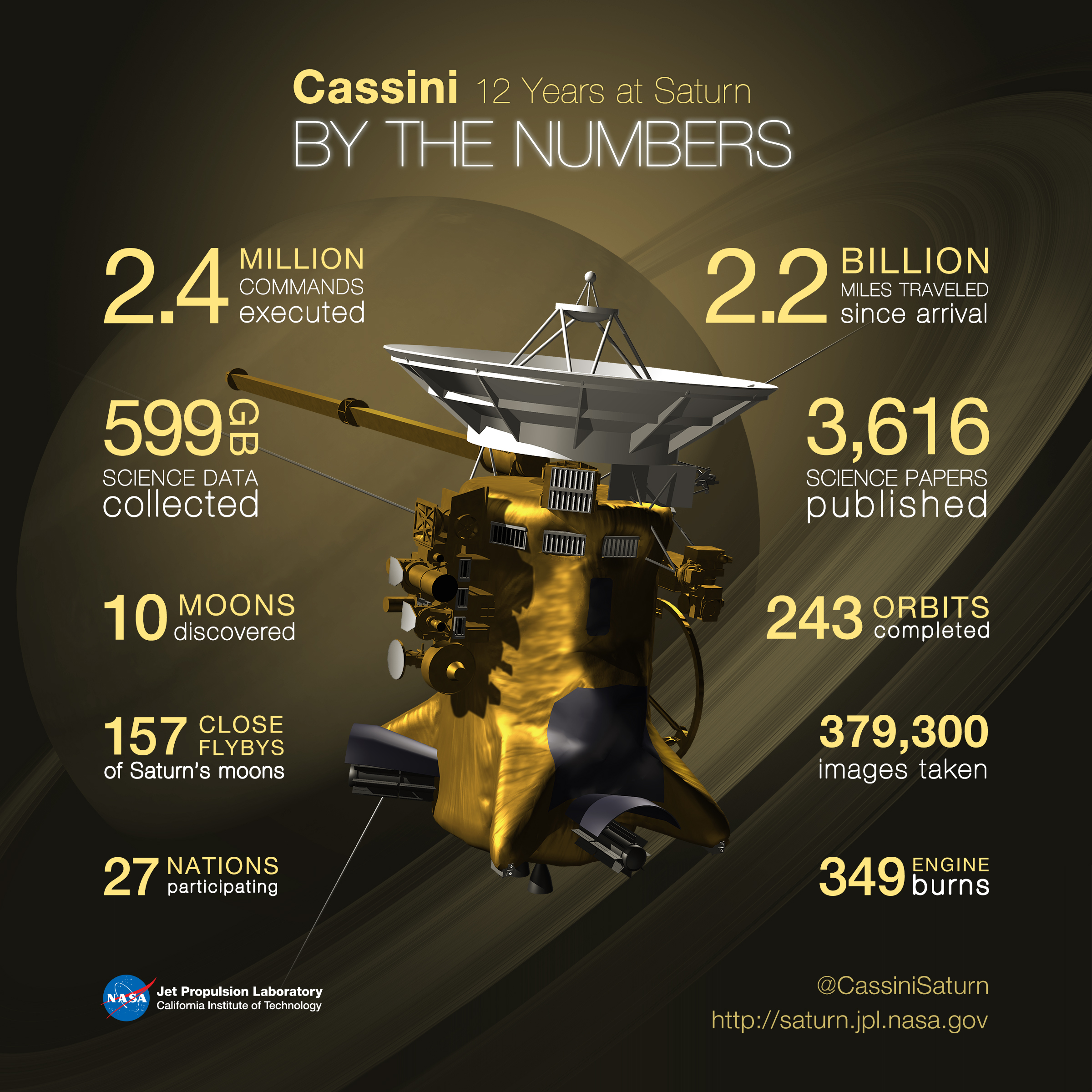

The Cassini spacecraft has studied Saturn for 12 years, and the probe has just one more year to go before its final dive into the planet itself.

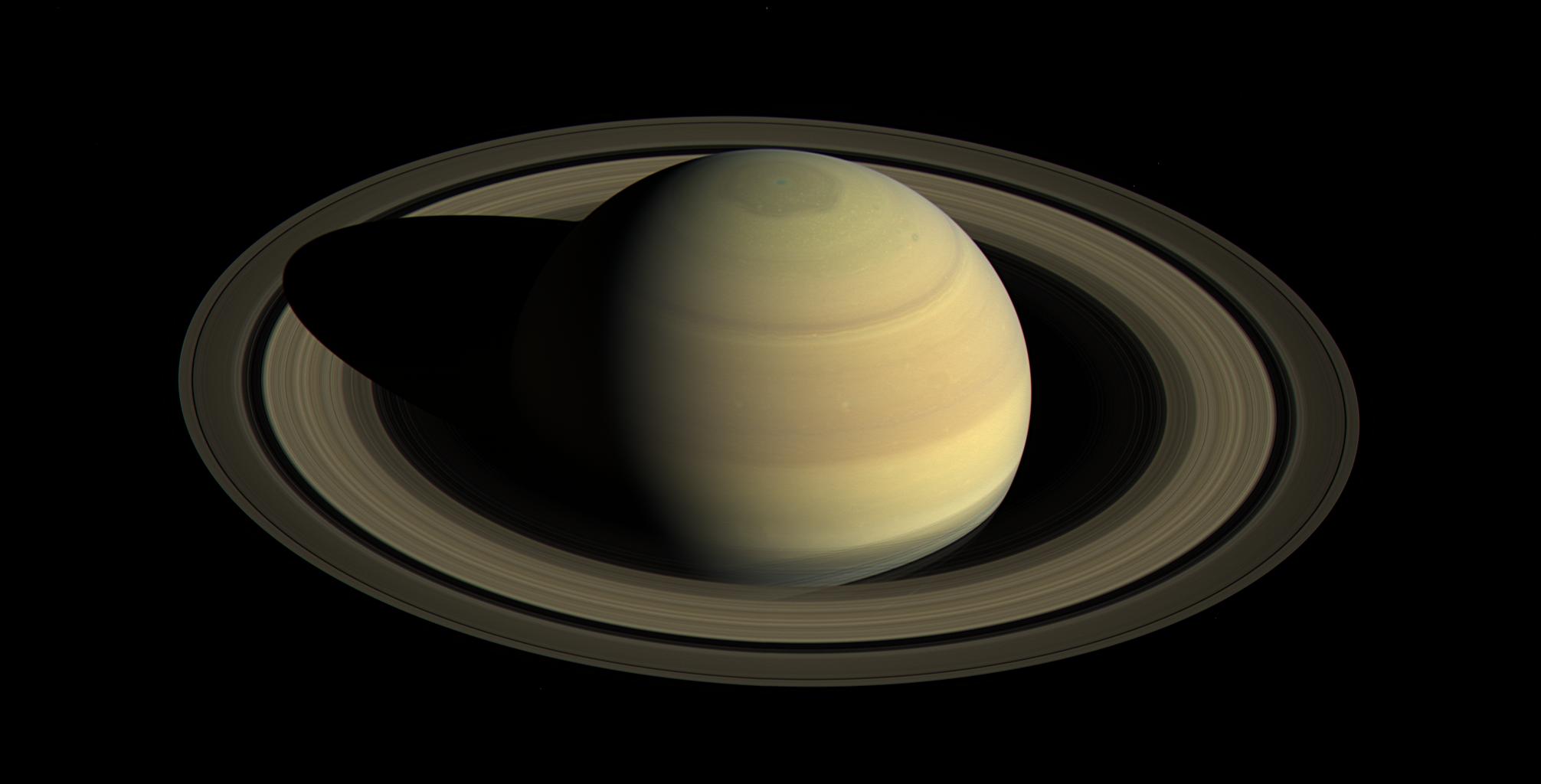

To celebrate the spacecraft's last year, Cassini's research team released an amazing new video tracking the ringed planet's atmosphere over the course of four Saturn "days," or 44 hours. Cassini picks up oval-shaped storms, faint inner rings and the great six-sided jet stream, which is slightly wider than Earth, on the planet's top.

Cassini first arrived in Saturn's system in 2004, and beginning Nov. 30, the probe will start in on its final two tasks: exploring Saturn's narrow F ring over the course of several orbits, and then flying past Saturn's large moon, Titan, to orbit between Saturn and its rings. Eventually, the probe will plunge into the planet's atmosphere. Once those observations start, Cassini will be way too close to take a broad view like in the newly released video, but the probe will give all-new insight into the big planet. [Inside Cassini's Mission to Explore Saturn (Infographic)]

"It's like getting a whole new mission," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, said in a statement. "The scientific value of the F-ring and Grand Finale orbits is so compelling that you could imagine a whole mission to Saturn designed around what we're about to do."

Engineers have been slowly changing Cassini's positioning in 2016 by flying by Titan to tilt the spacecraft's orbit higher and higher, preparing it to dive down past the rings for those final tasks: the 20 orbits past Saturn's F ring and 22 plunges between Saturn and its rings (a gap just 1,500 miles, or 2,400 kilometers, wide). That phase will start April 27 of next year.

"We've used Titan's gravity throughout the mission to sling Cassini around the Saturn system," Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL, said in the statement. "Now Titan is coming through for us once again, providing a way for Cassini to get into these completely unexplored regions so close to the planet."

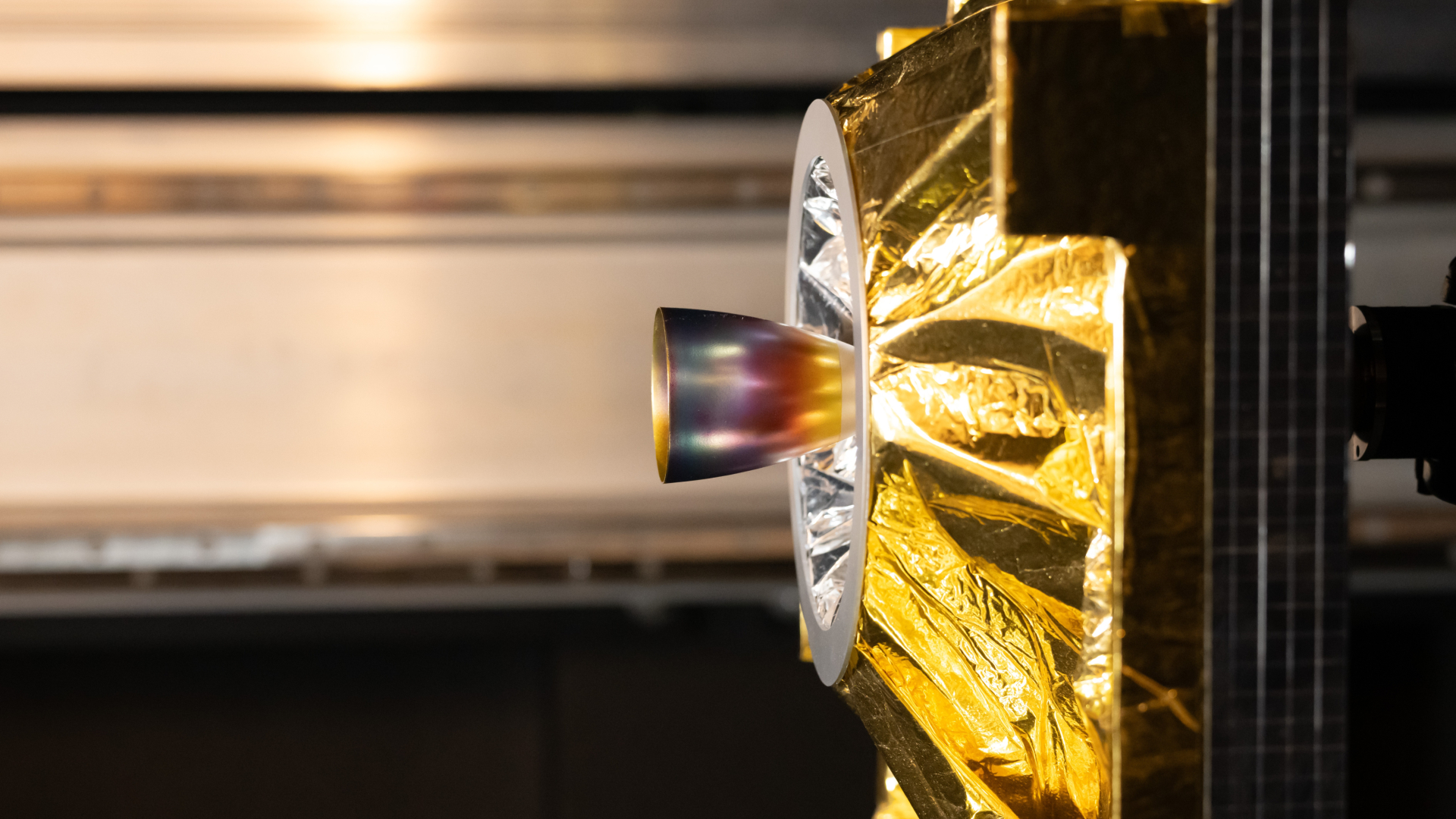

Sept. 15, 2017, Cassini will dive down into Saturn's atmosphere and send back one-of-a-kind data about the gas giant's chemistry. Soon after the probe's plunge, engineers will lose contact with the craft, researchers said in the statement. Soon after that, the spacecraft will burn up like a meteor due to friction with the planet's atmosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For the past 12 years, Cassini has explored Saturn's system, sending the Huygens lander to touch down on Titan; discovering huge plumes of water and a subsurface ocean on another Saturn moon, Enceladus; and cataloging the planet's many other moons and ever-changing ring system. JPL hosts a countdown to the end of Cassini's mission, at which point the probe will have also made detailed maps of Saturn's gravity and magnetic fields, analyzing samples from the planet's rings and capturing spectacular images up close to the ringed world.

"We may be counting down, but no one should count Cassini out yet," Curt Niebur, Cassini program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in the statement. "The journey ahead is going to be a truly thrilling ride."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.