Philae Lander, Like Philae Obelisk, Is a Window to the Past

Benjamin Altshuler is on the classics faculty at the University of Oxford and is the current Classics Conclave fellow at the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents. Altshuler is a specialist in reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), a computational photographic method that illuminates surface features undetectable by direct observation. He contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

"The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes." — Marcel Proust

Separated by two millennia, the Philae lander and the Philae obelisk illuminate two separate and shared paths of discovery. The Philae lander, recently launched from the European Space Agency (ESA) mothership Rosetta, is the robotic space vehicle that landed on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko last week in hopes of unlocking some of the secrets of ancient comets. The Philae obelisk, like the much better known Rosetta stone, helped unlock the ancient secrets of Egyptian hieroglyphs 200 years ago. Both are now connected by technology, as the same types of sensors aboard the Philae lander are now helping archaeologists unlock the obelisk's messages to reveal secrets about ancient Egypt.

A message in granite

The story begins 2,100 years ago, when a group of priests in Egypt successfully petitioned their king Ptolemy VIII for a tax cut. The priests created a permanent document of their success in the form of a 7-meter-tall (23 feet) granite obelisk. Never intending their success to be a hidden secret, the priests had their accomplishment inscribed onto the obelisk in Greek, with prayers written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, for all to see and understand forever.

However, by the fall of their eventual Roman conquerors 600 years later, the knowledge of hieroglyphs perished, and the obelisk's Egyptian inscription remained unreadable for centuries.

Then, in the 19th century, Egyptologist Jean-Francois Champollion used the recently discovered tri-lingual inscription on the Rosetta stone and the bilingual inscription on the Philae obelisk to decode hieroglyphs. While the importance of the Rosetta stone cannot be underplayed, the obelisk’s role in cementing hieroglyphs as a phonetic language was invaluable.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Digital eyes to see the past

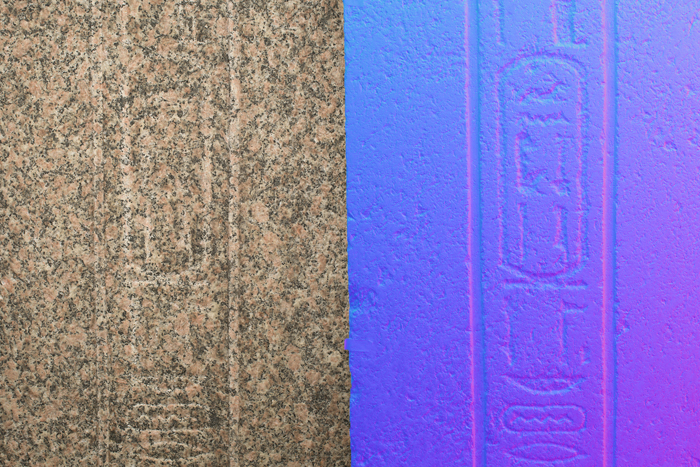

Now, new computer-based imaging technologies called polynomial texture mapping (PTM) and multispectral imaging (MSI) are allowing researchers to revisit the Philae obelisk and reveal parts of the inscriptions that have eroded with time.

While archaeology has often benefited from expanded excavations and deeper trenches, the field is now entering an age in which the most spectacular finds are not coming out of the ground but out of existing museum collections. Digital archaeology is allowing experts to uncover secrets in plain sight; indeed, to go beyond the boundaries of human sight and document sketch lines under layers of paint, transcribe badly eroded inscriptions and recover the faintest manuscripts.

With the power of these technologies growing exponentially, the next ground-breaking find could just as easily be discovered in the basement of a museum as under the streets of Cairo.

PTM is a powerful computational photographic technology that is literally shedding new light on ancient objects. Its ability to analyze the smallest features of surface topology has led to breakthroughs in the fields of epigraphy, archaeology and papyrology. The discoveries have been so frequent and significant that museums and archaeologists around the world are seeking to make PTM the standard international protocol for artifact documentation. Indeed, the age of digital archaeology has begun a quiet revolution in classical studies. Scholars no longer feel limited by what they can see with their own eyes.

More than anything else, it is the sheer volume of data gathered by PTM that sets it apart from what is currently the most common documentation methods used in museums: simple photography. While a conventional photograph can adequately capture color information, it can only convey a very crude sense of shape and surface texture through a fixed number of highlights and shadows.

By contrast, PTM, in addition to capturing superb color data, can record detailed shape and texture measurements at the level of individual pixels. This massive quantity of incremental data not only provides a far more comprehensive method for object documentation than simple photography can, but it also opens up a range of opportunities for computer-driven rendering techniques — potentially including the use of 3D printers — for creating highly detailed depictions of objects for study and analysis. PTM combines digital photography, specialized lighting techniques and sophisticated computer software to combine dozens of images into an interactive image that enables researchers to read worn inscriptions or recover artistic details.

Current PTM work has already allowed researchers to confirm early transcriptions of the hieroglyphic and Greek text on the Philae obelisk and to begin studying the tool marks. In the coming weeks, epigraphists will also employ MSI and focus on the Greek text at the base of the obelisk where significant portions of the text are almost completely eroded, leaving huge swaths of text unaccounted for.

It is hoped that ultraviolet and infrared light will pick up some of the original paint that adorned the obelisk and help researchers read more of the text to get a better understanding of the exact correspondence between Ptolemy VIII and the priests of Philae. Moreover, in a language where a single word, or even a single letter, can change the entire meaning of a sentence, every single minim picked up by PTM could contribute to, or even change, our current understanding.

Digital eyes in space

Meanwhile, 300 million miles away at comet 67P, the Philae lander is equipped with ROLIS (Rosetta-Lander Imaging System) and CIVA (Comet Nuclear Infrared and Visible Analyzer), both of which use digital imaging technologies and multispectral analyzers to "see" the comet and send images back to Earth.

Over the next several months, scientists will use the same spectral properties that researchers are using to pick up traces of paint on the obelisk, albeit of different elements, to analyze and isolate the exact makeup of the comet. By understanding this, more can be learned about the origins of comet 67P, other comets in our solar system and the nature of the entire solar system.

Although the Philae lander has now run out of power due to a malfunction in the landing apparatus, the data gathered in its short time on the comet is currently being analyzed by scientists and looks to shed light on many of the questions posed at the beginning of the mission. As the comet gets closer and closer to the sun, Rosetta will have to take over the mission continue to use mapping technologies similar to PTM to assess the changes in the topography of the comet. By monitoring 67P's vital signs constantly, scientists look forward to seeing a process that has only ever been observed from millions of miles away.

It is powerful to recognize that so many technologies being used in space to lead scientists to the origins of the solar system have equally valuable uses on Earth, helping archaeologists uncover lost secrets of the past.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitterand Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.