Microbes Found Beneath Antarctic Ice: What It Means for Alien Life Hunt

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The discovery of a complex microbial ecosystem far beneath the Antarctic ice may be exciting, but it doesn't necessarily mean that life teems on frigid worlds throughout the solar system, researchers caution.

Scientists announced today (Aug. 20) in the journal Nature that many different types of microbes live in subglacial Lake Whillans, a body of fresh water entombed beneath 2,600 feet (800 meters) of Antarctic ice. Many of the micro-organisms in these dark depths apparently get their energy from rocks, the researchers report.

The results could have implications for the search for life beyond Earth, notes Martyn Tranter of the University of Bristol in England, who did not participate in the study. [6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System]

"The team has opened a tantalizing window on microbial communities in the bed of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and on how they are maintained and self-organize," Tranter wrote in an accompanying "News and Views" piece in the same issue of Nature. "The authors' findings even beg the question of whether microbes could eat rock beneath ice sheets on extraterrestrial bodies such as Mars. This idea has more traction now."

But just how much traction is a matter of debate. For example, astrobiologist Chris McKay of NASA's Ames Research Center in California doesn't see much application to Mars or any other alien world.

"First, it is clear that the water sampled is from a system that is flowing through ice and out to the ocean," said McKay, who also was not part of the study team.

"Second, and related to this, the results are not indicative of an ecosystem that is growing in a dark, nutrient-limited system," McKay told Space.com via email. "They are consistent with debris from the overlying ice — known to contain micro-organisms — flowing through and out to the ocean. Interesting in its own right, but not a model for an isolated ice-covered ecosystem."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

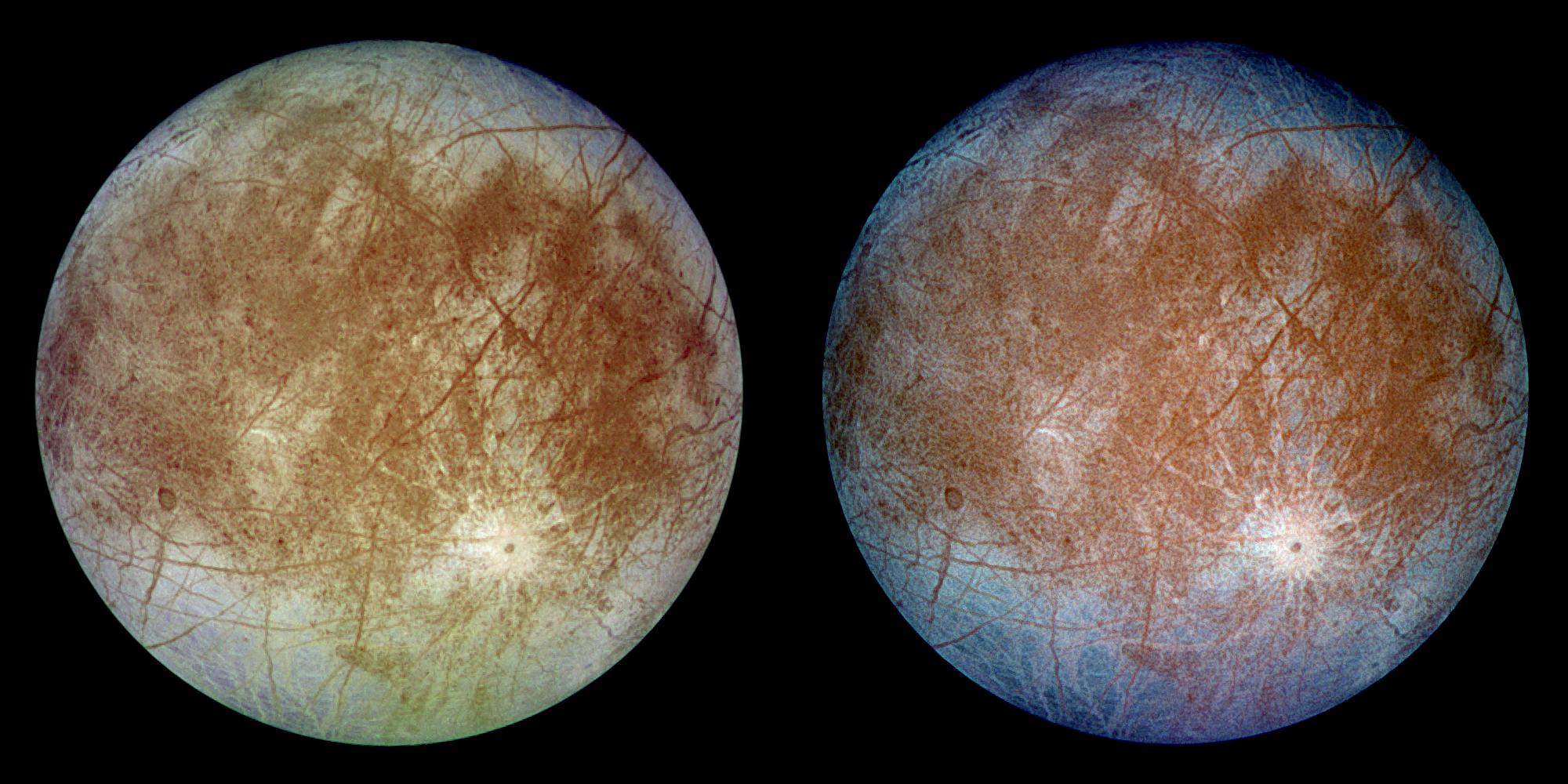

Isolated, ice-covered oceans exist on some moons of the outer solar system, such as Jupiter's moon Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus — perhaps the two best bets to host life beyond Earth. McKay and other astrobiologists would love to know if these oceans do indeed host life.

It may be possible to find out without even touching down on Europa or Enceladus. Plumes of water vapor spurt into space from the south polar regions of both moons, suggesting that flyby probes could sample their subsurface seas from afar.

And Europa is on the minds of the higher-ups at both NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA). NASA is drawing up plans for a potential Europa mission that could blast off in the mid-2020s, while ESA aims to launch its JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission —which would study the Jovian satellites Callisto and Ganymede in addition to Europa — in 2022.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.