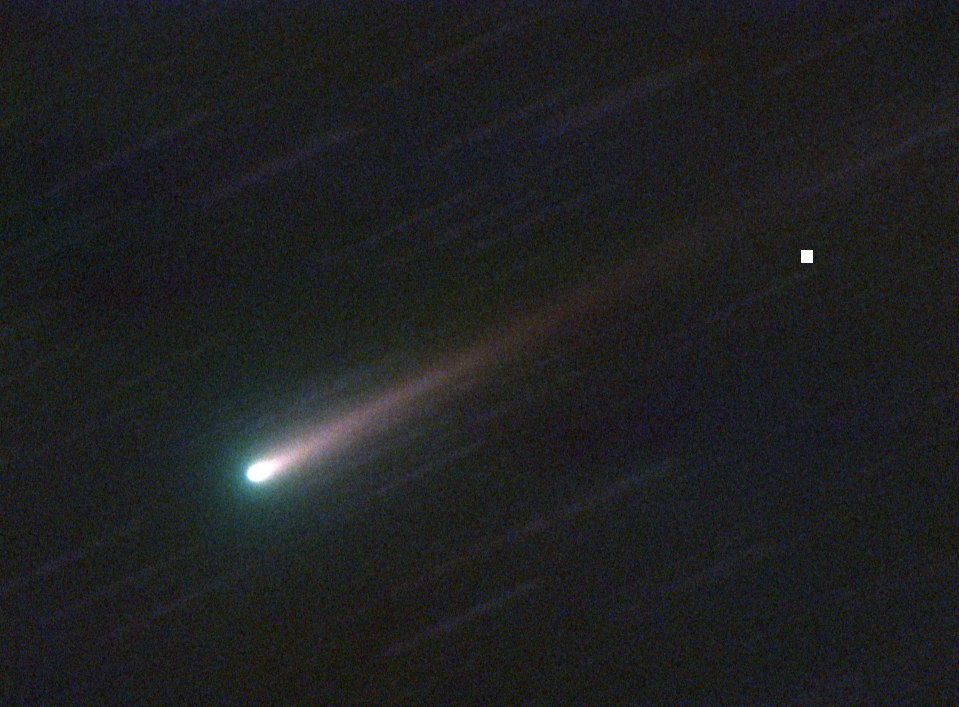

Earth Impact: Are Comets a Bigger Danger Than Asteroids?

Discussions about "death from above" scenarios usually center on asteroids, but a comet impact could be far more devastating than a space rock strike.

Near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) have Earth-like orbits, so their collisions with Earth tend to be glancing blows from behind or from the side. But comets travel around the sun in more random paths and can thus slam into the planet head-on, with potentially catastrophic results, researchers say.

"It would be a much bigger explosion, a much bigger crater, much more damage," impact expert Mark Boslough, of Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, said on June 5. He made the comment during a webcast produced by the online Slooh community observatory, which previewed the June 8 Earth flyby of the asteroid 2014 HQ124. [Amazing Comet Photos of 2013 by Stargazers]

In fact, comets can be traveling up to three times faster than NEAs relative to Earth at the time of impact, Boslough added. The energy released by a cosmic collision increases as the square of the incoming object's speed, so a comet could pack nine times more destructive power than an asteroid of the same mass.

The speed of comets also means that a dangerous one could be nearly upon Earth by the time scientists detect it.

"They come in fast," Bill Ailor, principal engineer with the Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies at The Aerospace Corporation, said in March during a presentation with NASA's Future In-Space Operations working group. "In some cases, people have said that we may have two years' or so warning in the best case on something like that."

Two years may sound like a lot, but scientists and engineers would prefer even more lead time to keep Earth out of harm's way.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For example, one of the most promising deflection strategies envisions launching a robotic probe to rendezvous with and fly alongside of the incoming object, nudging it off course via a slight but persistent gravitational tug. This "gravity tractor" method obviously cannot work overnight.

Adding to the intrigue and the danger is the unpredictability of cometary orbits. The icy objects begin spouting gas as they near the sun and heat up; these gas jets act like little thrusters, making it tough to forecast exactly where a comet is going to go.

Despite all of these factors, however, the focus on asteroids as Earth's primary impact threat is not misplaced, Boslough and Ailor said. The reason is simple: numbers.

"I'm more worried about asteroids than I am comets, because there are so many more asteroids," Boslough said. "The likelihood of an impact from an asteroid is probably 100 times the likelihood of an impact from a comet of the same size."

There are probably trillions of comets out there, but the vast majority of them reside at the extreme outer edge of the solar system, in a shell of icy bodies known as the Oort Cloud. Near-Earth space, meanwhile, is dominated by asteroids. Scientists think millions of NEAs exist, but only about 11,000 have been discovered and tracked so far.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.