Why the Moon's 'Dark Side' Has No Face

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Heat radiating from the young Earth could help solve the more than 50-year-old mystery of why the far side of the moon, which faces away from Earth, lacks the dark, vast expanses of volcanic rock that define the face of the Man in the Moon as seen from Earth, researchers say.

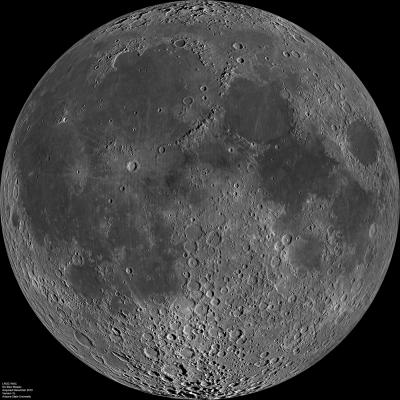

The Man in the Moon was born when cosmic impacts struck the near side of the moon, the side that faces Earth. These collisions punched holes in the moon's crust, which later filled with vast lakes of lava that formed the dark areas known as maria or "seas."

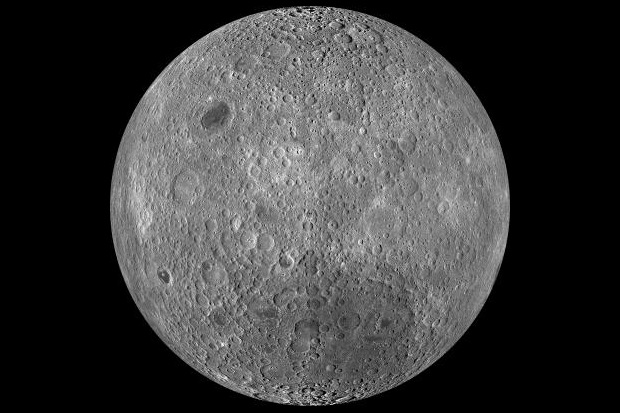

In 1959, when the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 transmitted the first images of the "dark" or far side of the moon, the side facing away from Earth, scientists immediately noticed fewer maria there. This mystery — why no Man in the Moon exists on the moon's far side — is called the Lunar Farside Highlands Problem. [How the Moon Evolved: A Photo Timeline]

"I remember the first time I saw a globe of the moon as a boy, being struck by how different the far side looks," study co-author Jason Wright, an astronomer at Pennsylvania State University, said in a statement. "It was all mountains and craters. Where were the maria?"

Now scientists may have solved the 55-year-old mystery; heat from the young Earth as the newborn moon was cooling caused the difference. The researchers came up with the solution during their work on exoplanets, which are worlds outside the solar system.

"There are many exoplanets that are really close to their host stars,"lead study author Arpita Roy, also of Penn State, told Space.com. "That really affects the geology of those planets."

Similarly, the moon and Earth are generally thought to have orbited very close together after they formed. The leading idea explaining the moon's formation suggests that it arose shortly after the nascent Earth collided with a Mars-size planet about 4.5 billion years ago, with the resulting debris coalescing into the moon. Scientists say the newborn moon and Earth were 10 to 20 times closer to each other than they are now.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The moon and Earth loomed large in each other's skies when they formed, " Roy said in a statement.

Since the moon was so close to Earth, the mutual pull of gravity was strong. The gravitational tidal forces the moon and Earth exerted on each other braked their rotations, resulting in the moon always showing the same face to Earth, a situation known as tidal lock.

The moon and Earth were very hot shortly after the giant impact that formed the moon. The moon, being much smaller than Earth, cooled more quickly. Since the moon and Earth were tidally locked early on, the still-hot Earth — more than 4,530 degrees Fahrenheit (2,500 degrees Celsius) — would have cooked the near side of the moon, keeping it molten. On the other hand, the far side of the moon would have cooled, albeit slowly.

The difference in temperature between the moon's halves influenced the formation of its crust. The lunar crust possesses high concentrations of aluminum and calcium, elements that are very hard to vaporize.

"When rock vapor starts to cool, the very first elements that snow out are aluminum and calcium," study co-author Steinn Sigurdsson of Penn State said in a statement.

Aluminum and calcium would have more easily condensed in the atmosphere on the colder far side of the moon. Eventually, these elements combined with silicates in the mantle of the moon to form minerals known as plagioclase feldspars, making the crust of the far side about twice as thick as that of the near side.

"Earthshine, the heat of Earth soon after the giant impact, was a really important factor shaping the moon," Roy said.

When collisions from asteroids or comets blasted the moon's surface, they could punch through the near side's crust to generate maria. In contrast, impacts on the far side's thicker crust failed to penetrate deeply enough to cause lava to well up, instead leaving the far side of the moon with a surface of valleys, craters and highlands, but almost no maria.

"It's really cool that our understanding of exoplanets is affecting our understanding of the solar system," Roy said.

Future research could generate detailed 3D models testing this idea, Roy suggested. The authors detailed their findings June 9 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us