AI helps astronomers make a potentially major find — an exploding star being attacked by a black hole

"We're now entering an era where we can automatically catch these rare events as they happen, not just after the fact."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

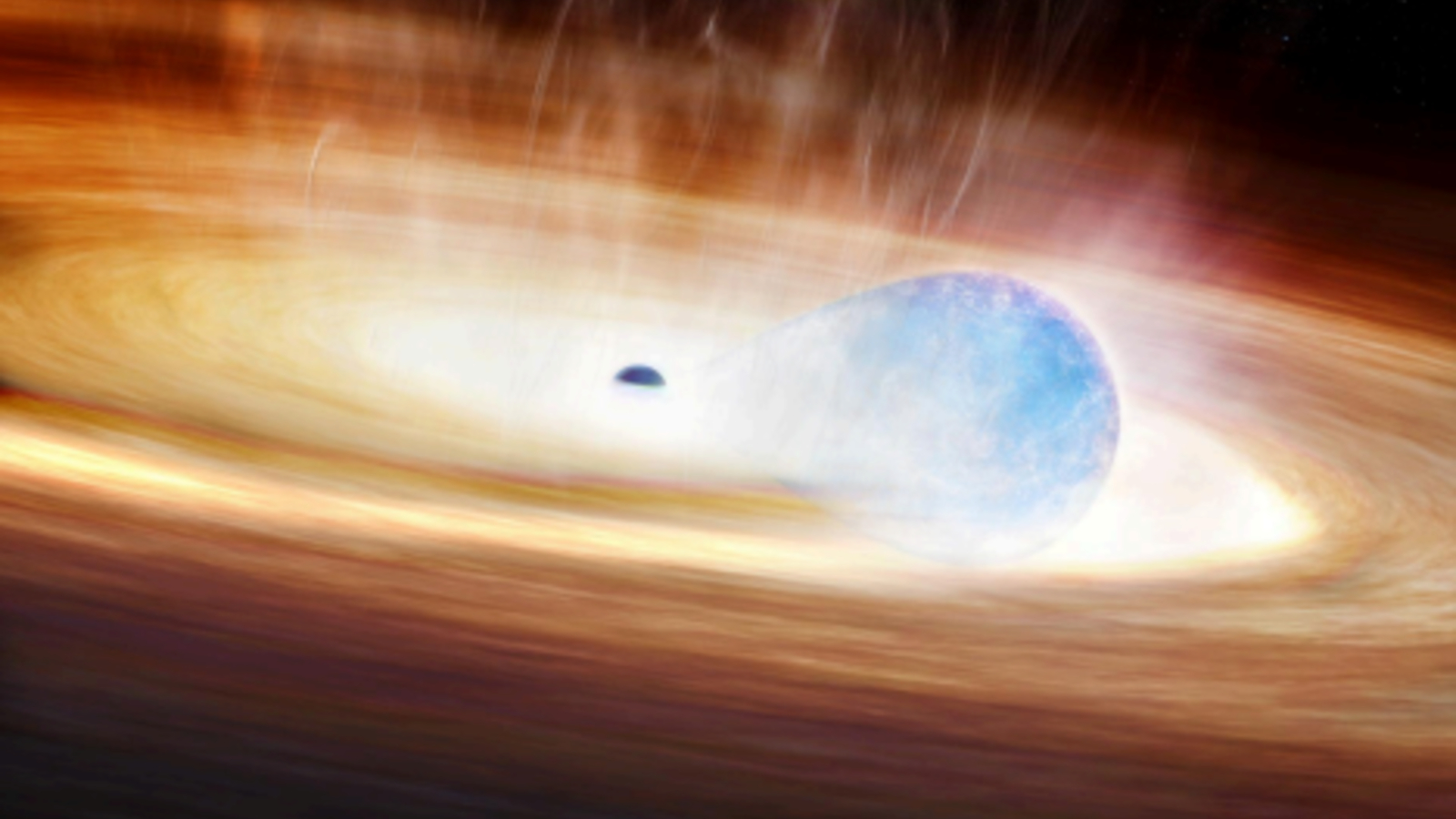

Astronomers have observed what may be the first known case of a massive star exploding while interacting with a black hole, marking a discovery that could reveal an entirely new class of stellar explosions.

The event, named SN 2023zkd, was first spotted in July 2023 by the Zwicky Transient Facility in California. Located in a galaxy with little ongoing star formation about 730 million light-years away, it was detected by a new artificial intelligence (AI) system built to flag unusual cosmic events in real time. The early alert allowed telescopes worldwide and in space to begin observations immediately, capturing the event from its earliest stages, according to a statement.

"2023zkd shows some of the clearest signs we've seen of a massive star interacting with a companion in the years before explosion," Ashley Villar, an assistant professor of astronomy at Harvard University in Massachusetts and a co-author of the new study, said in the statement. "We think this might be part of a whole class of hidden explosions that AI will help us discover."

At first, SN 2023zkd appeared to be a typical supernova: a bright flash signaling the death of a massive star that slowly fades over time. But months later, astronomers noticed it brightened again. Looking back at archival data, they found the system had been gradually increasing in brightness for about 1,500 days — roughly four years — before the explosion. Such a long-lived pre-explosion phase is rarely seen, and it suggests the star was under intense gravitational stress.

The researchers say the most likely explanation is the star was locked in orbit with a black hole. Evidence from light curves and spectra indicates the star underwent two major eruptions in the years before it died, shedding large amounts of gas. The explosion's first light peak came when the blast wave struck low-density material, while the second peak months later was caused by a slower, sustained collision with a dense, disk-shaped cloud.

Over time, the black hole's gravity could have destabilized the star, pushing it to collapse.

Another possibility, the team believes, is the black hole destroyed the star before it could explode naturally. In that case, the debris would have produced the supernova's light as it crashed into surrounding gas. In either scenario, the aftermath would be a single, heavier black hole.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SN 2023zkd "is the strongest evidence to date that such close interactions can actually detonate a star," study lead author Alexander Gagliano, a researcher at the Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Fundamental Interactions, said in the statement.

"We've known for some time that most massive stars are in binaries, but catching one in the act of exchanging mass shortly before it explodes is incredibly rare."

The findings highlight how AI can spot rare cosmic events in time for detailed study, the astronomers say. They also point to the role upcoming facilities such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will play over the next decade, thanks to its ability to document the entire southern sky every few nights from its vantage point in the Chilean Andes mountains.

Combined with real-time AI detection, observations gathered by the Rubin Observatory will enable astronomers to identify and study more of these rare, complex events, helping to build a clearer picture of how massive stars live and die in binary systems.

"We're now entering an era where we can automatically catch these rare events as they happen, not just after the fact," Gagliano said in the statement. "That means we can finally start connecting the dots between how a star lives and how it dies, and that's incredibly exciting."

This research is described in a paper published Wednesday (Aug. 13) in the Astrophysical Journal.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.