James Webb Space Telescope discovers 'Cosmic Vine' of 20 connected galaxies in the early universe

The James Webb Space Telescope has discovered a massive chain of 20 galaxies in the early universe, raising questions about the formation of the largest structures in the cosmos.

Astronomers using James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) data have discovered a massive chain of at least 20 closely packed galaxies from the early universe, and it could reveal insight into how the most massive structures in the cosmos form.

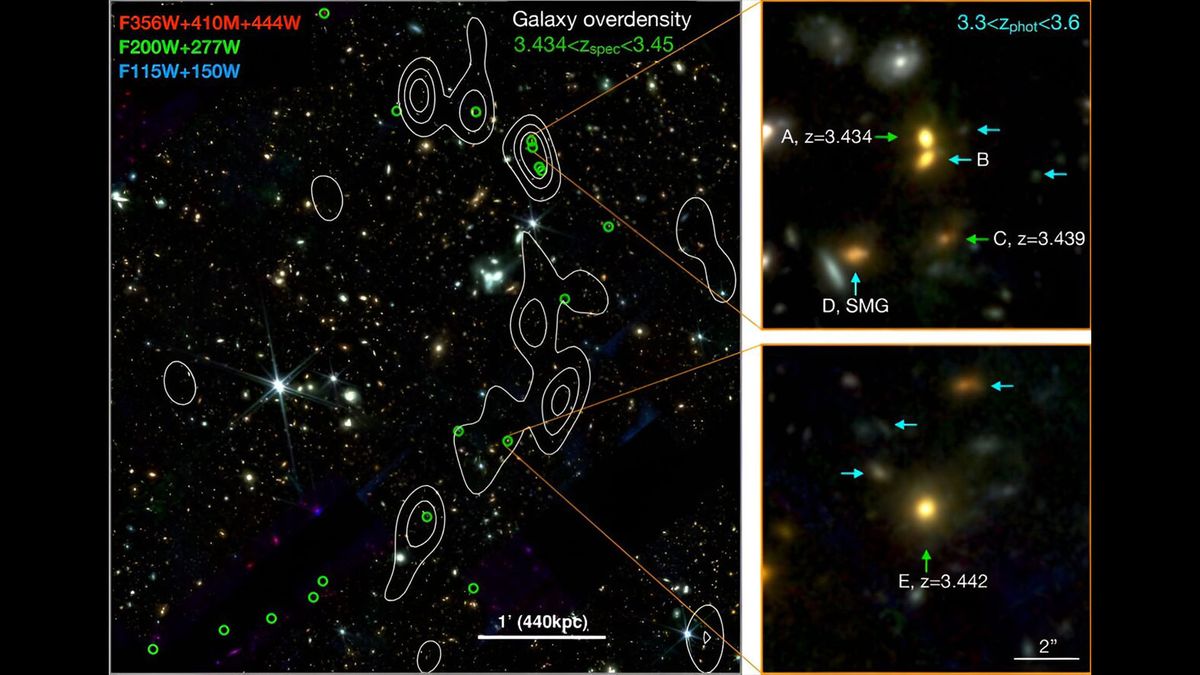

This megastructure — nicknamed the "Cosmic Vine" in a study published Nov. 8 to the preprint database arXiv — swoops through space in a bow shape, estimated to stretch more than 13 million light-years long and about 650,000 light-years wide. (For comparison, our Milky Way galaxy is about 100,000 light-years wide.) Astronomers detected the vast tendril of gas and galaxies while studying James Webb Space Telescope observations of an area called the Extended Groth Strip, located between the constellations Ursa Major and Boötes.

The team was looking specifically for light from very early galaxies, focusing on a property called redshift, a measure of how light increases in wavelength as it travels vast distances through the expanding universe. All of the galaxies observed in the Cosmic Vine showed a redshift of roughly 3.44, meaning the light emitted by the objects traveled between 11 billion and 12 billion years — or for most of our 13.8 billion-year-old universe's lifetime — before reaching JWST's lens.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope sees major star factory near the Milky Way's black hole (image)

The Cosmic Vine is "significantly larger" than other galaxy groups observed so early in the universe's history, the team wrote, adding it to a growing list of surprisingly huge structures in the early universe discovered by JWST. According to the researchers, the Vine appears to be on its way to becoming a galaxy cluster; these are the most massive structures in the universe bound together by gravity, with masses typically ranging from hundreds of billions to quadrillions of times the mass of the sun.

For now, the Cosmic Vine has an estimated mass of about 260 billion solar masses and is still growing — but its two largest galaxies may be ready to call it quits. While studying the wavelengths of light emitted by the two galaxies, the researchers found that star formation has all but stopped there, designating them as "quiescent" or "quenched" galaxies.

The authors pondered, what is "the culprit quenching star formation" at such an early cosmic time? They noted that it is unusual to find such large galaxies already running low on star-forming gas in the ancient universe. One possibility is that both galaxies are the results of recent galactic mergers, with cosmic collisions triggering wild bursts of star formation that depleted most of the galaxies' available gas about half a billion years before JWST's observations, the researchers wrote.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As with many recent JWST discoveries, the Cosmic Vine raises more questions about the nature of our universe than it answers, and further study is needed to solve the mysteries locked behind this ancient galactic chain.

Originally published on LiveScience.com.

Brandon has been a senior writer at Live Science since 2017, and was formerly a staff writer and editor at Reader's Digest magazine. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.