The weird ringed dwarf planet Quaoar may have an extra moon, astronomers discover

"The profile of the occultation was most consistent with it being a new satellite — a new moon — going around Quaoar."

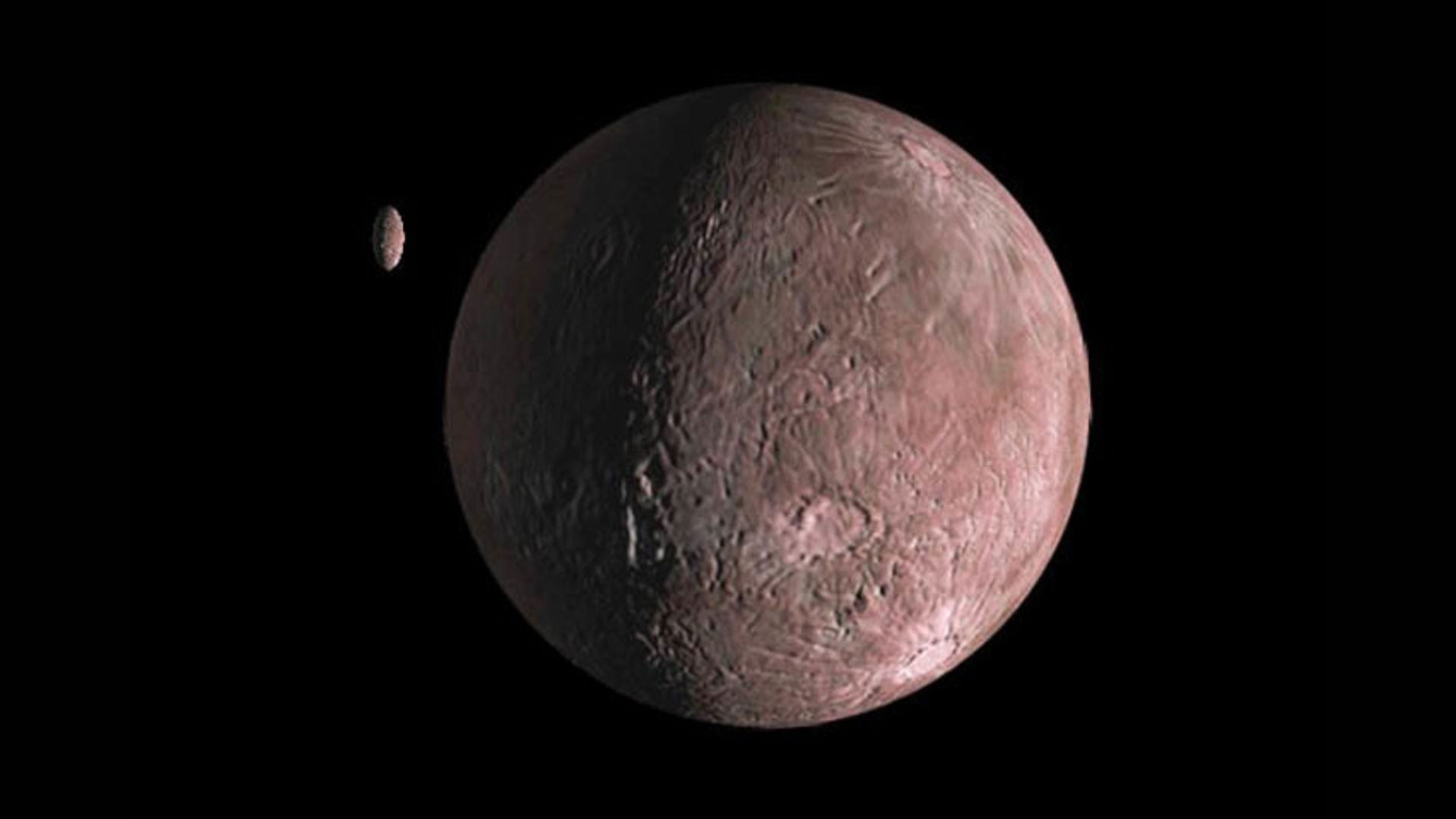

The odd dwarf planet Quaoar might have a brand-new moon. Observations of the tiny world, made by a pair of astronomers in California, suggest it possesses either a second satellite or a third ring.

Quaoar and our solar system's other dwarf planets are generally so far away that they are a challenge to view directly from Earth. (An exception is Ceres, which lies in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.) So, to observe them, astronomers rely on stellar occultations — moments when an object passes between them and a background star. The body of the foreground object briefly blocks light from the star, as do any rings or satellites.

Both of Quaoar's known rings were discovered in separate occultations, with the first ring initially identified by a trio of amateur astronomers.

But occultation observations can be tricky. Seeing rings depends on the angle of their orbit, which can miss the star completely. And moons must be in the right position in their journey around their parent object to block the star, so spotting them can be hit or miss. And occultations themselves depend on the viewer's location on Earth, as the viewing angle shifts with latitude.

On June 25, 2025, Rick Nolthenius, an astronomer at Cabrillo College in Aptos, California, and his former student, amateur astronomer Kirk Bender, set out to observe the Quaoar system during an occultation. The roughly 680-mile-wide (1,090 kilometers) dwarf planet would pass in front of the background star at an angle visible only to observers in northern Canada and other parts of the Arctic during daylight hours. But one of the rings might manage an occultation that could be seen from California. It was enough to send Nolthenius and Bender south to the Monterey Institute for Research in Astronomy, where an observing partnership was set up.

With Nolthenius on the institute's 36-inch telescope and Bender on the 14-inch one, they anxiously awaited the potential passage.

"I did decide to start the recording earlier," Nolthenius told Space.com. "I thought, Who knows what we're going to see?"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So they had their separate systems up and running four minutes before the anticipated occultation. Their optimism paid off.

"I said, 'Oh my God, did you see that? The star disappeared,'" Nolthenius said.

It was a brief flicker, lasting just over a second, and Bender hadn't seen it. But both telescopes did. The recordings showed a brief 1.23-second blip.

"The profile of the occultation was most consistent with it being a new satellite — a new moon — going around Quaoar," Nolthenius said.

The results were published this past August in an article in the journal Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society.

'Keep recording'

Quaoar was discovered in 2002. The dwarf planet orbits beyond Pluto, taking 286 Earth years to complete one lap of the sun. Its name comes from the creation mythology of the Tongva people, who are indigenous to the Los Angeles Basin, where the initial observations were made. The name can be pronounced with two syllables (/ˈkwɑːwɑːr/) or three (/ˈkwɑːoʊ(w)ɑːr/).

In 2007, Quaoar's only confirmed moon, named Weywot, was spotted. The dwarf planet's rings are a puzzle. The pair orbit a significant distance from the icy world, farther out in relation to the dwarf planet's size than expected. Their extensive reach required astronomers to revise what they thought they knew about the survival of planetary rings.

It's possible that the new observations by Nolthenius and Bender indicate not a moon but a third ring. The duo have been cautious in their classification, allowing for the possibility that a torus of material could be behind the observations. But Nolthenius doesn't think that's likely.

"As soon as I saw that occultation, I decided, OK, we're going to keep recording," he said.

The pair continued to observe for a full three minutes after the planned occultation time, for a total time of nine minutes. They saw no sign of a second occultation, which they would have expected had a ring been involved. However, the duo still doesn't rule a ring out as a possibility.

Study co-author Benjamin Proudfoot, an astronomer at the University of Central Florida, also thinks that a newfound satellite is the most likely explanation. Proudfoot observed Quaoar in 2024 using NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, work that allowed him to place constraints on the ring system in a paper published earlier this year in The Planetary Science Journal.

"We think we found a new moon," Proudfoot told colleagues in July at the Progress in Understanding the Pluto Mission: 10 Years after Flyby conference in Laurel, Maryland, where he reported the discovery.

Checking the boxes

Rings and moons aren't the only potential explanations for blockages seen during occultations. Nolthenius and his colleagues had to rule out several other possibilities.

Perhaps the easiest was an airplane flying overhead. In addition to Nolthenius and Bender, a handful of other observers were present, and they watched the area of the sky for aircraft; none were spotted in the region during the occultation. A large bird could theoretically block both telescopes, and Nolthenius said that California condors are native to the region. But "they don't hover," he said, and that would be necessary to block both telescopes for more than a second.

What about a drone, which could easily manage the feat? Nolthenius pointed out that such a craft would have to be very large, at least 80 inches (200 centimeters) wide, and would have to be precisely targeted to hover in such a way that it would block both telescopes — in other words, sent to "mess with those astronomers." It would have to move into position, stop on a dime, remain for less than two seconds, and then leave.

"That would take a drone mastery beyond what I think is possible," Nolthenius said.

The team then vetted objects beyond Earth. Satellites orbiting our planet would block out light for less than a second. Interference by known asteroids would have been identified by the International Occultation Timing Association, which provides times to interested parties for occultations around the world.

What about unknown asteroids? An asteroid that has remained undiscovered to date would have produced a shorter event, and it would be unlikely to block light completely, according to the researchers.

The final potential obstructor was the Quaoar's known moon, Weywot. But it was casting its shadow further south, from an observer's perspective; occultations it may have produced would have been seen from Costa Rica, not California.

According to Proudfoot's calculations, the newfound Quaoar moon — if it does indeed exist — is at least 19 miles (30 km) wide. It appears to be moving in a special orbit known as a resonance with the outermost ring, making three trips around Quaoar for every five made by the annulus. Those numbers are rough estimates, because they are based on a single observation.

Full confirmation will come as other astronomers make observations of the moon. But that could be a challenge.

"Right now, we have a pretty good idea of what its orbit should look like, but not where along that possible orbit it could be," Proudfoot told Space.com by email. Observing it again would essentially require a blind search. He said it's likely that the moon is only visible in a telescope like Webb when it is farthest from Quaoar, making it even more challenging to observe.

"It's on the bleeding edge of detectability," Proudfoot said.

Nolthenius hopes that more astronomers – professionals and amateurs – will turn their eyes to the skies to observe Quaoar's occultations. Right now, the dwarf planet is passing in front of a region of the sky filled with stars. Once it moves on, he said, occultations will be much less common for the next 200 years.

If the new moon is confirmed, Nolthenius will have the chance to name it. He indicated that he's considering naming it after "someone special to me," but he's not sure how to make that work with the International Astronomical Union's naming conventions. (Small objects in the outer solar system are generally named after deities associated with the underworld or creation). Regardless, confirmation will likely take some time.

Meanwhile, both Nolthenius and Bender will continue hunting for occultations of Quaoar and other targets. The pair plan to observe more than a hundred occultations this year, roughly the same number they hunted last year.

"It's a little microadventure," Nolthenius said of occultation hunting. "I get to go off and do some science and not think about anything else."

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.