RIP, Cassini: Historic Mission Ends with Fiery Plunge into Saturn

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

PASADENA, Calif.— And just like that, it was gone.

NASA received its last data transmission from the Cassini spacecraft at 4:55:46 a.m. PDT (7:55:46 a.m. EDT, 1146 GMT) today (Sept. 15), before losing contact with the probe as it hurtled into Saturn's atmosphere. It was a fiery grand finale for the probe, which spent 13 years orbiting the ringed planet. NASA officials expect that Cassini broke apart about 45 seconds after that final transmission, due to the intense friction and heat generated by the fall.

"I hope you're all ... deeply proud of this amazing accomplishment," Earl Maize, the Cassini program manager, said to the mission team after the spacecraft signal was lost. "Congratulations to you all. This has been an incredible mission, an incredible spacecraft, and you're all an incredible team. I'm going to call this the end of mission." [In Photos: Cassini's Last Views of Saturn at Mission's End]

The final stream of data from Cassini was received at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in southern California. The spacecraft communicated with Earth via the Deep Space Network, a series of telescopes around the world that keep contact with spacecraft that fly beyond the moon. The Deep Space Network is managed from JPL.

During Cassini's final moments, mission scientists and team members watched anxiously as data continued to come in from the spacecraft as it hurtled through Saturn's atmosphere. The signal was lost when Cassini could no longer keep its antenna pointed at Earth, due to the intense friction created by its fall through the atmosphere. Maize said he anticipated that the probe would completely break apart about 45 seconds later. The team members stood and applauded somberly when Maize announced end of mission.

"This is a historic moment, and I think the mood reflects that," Morgan Cable, a research scientist at JPL, said of the event. "This is a celebration of an amazing mission and incredible legacy."

In Cassini's final months and days, scientists and the public alike have voiced their affection for the space probe and the incredible discoveries it made.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"[I'm] feeling the love, if I may be so corny," Maize said when asked about the public outpouring. "It's just very heartening. Because it's part of what we try to do — to extend everybody out to Saturn. It's not [just for] scientists in the ivory tower; it's for humanity. And so for everybody to get on the ride … it is just phenomenal." [Cassini's Greatest Discoveries at Saturn]

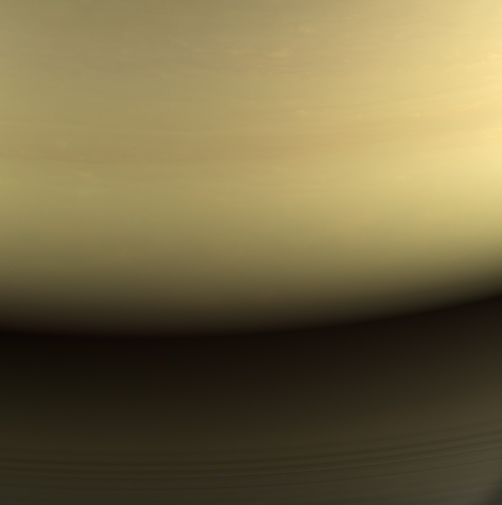

Cassini's descent into Saturn was intentional. The spacecraft was rapidly running out of fuel, after spending nearly 20 years in space, and NASA scientists decided to make use of the mission's inevitable conclusion. By crashing into Saturn, Cassini had the opportunity to see what the planet's upper atmosphere is made of, and that's the data that the probe sent back to Earth during its final few moments of life. The probe took its last images of the Saturn system yesterday (Sept. 14), and transmitted those images back to Earth the same day, ahead of its plunge.

During its 13-year tenure at Saturn, Cassini captured breathtaking images of the ringed planet, revealing swirling storms and a hexagonal jet stream swirling around Saturn's north pole. The probe saw strange features in the planet's ring system, found evidence of meteors crashing through the rings in the past, and watched as the planet's many moons caused the rings to change and evolve.

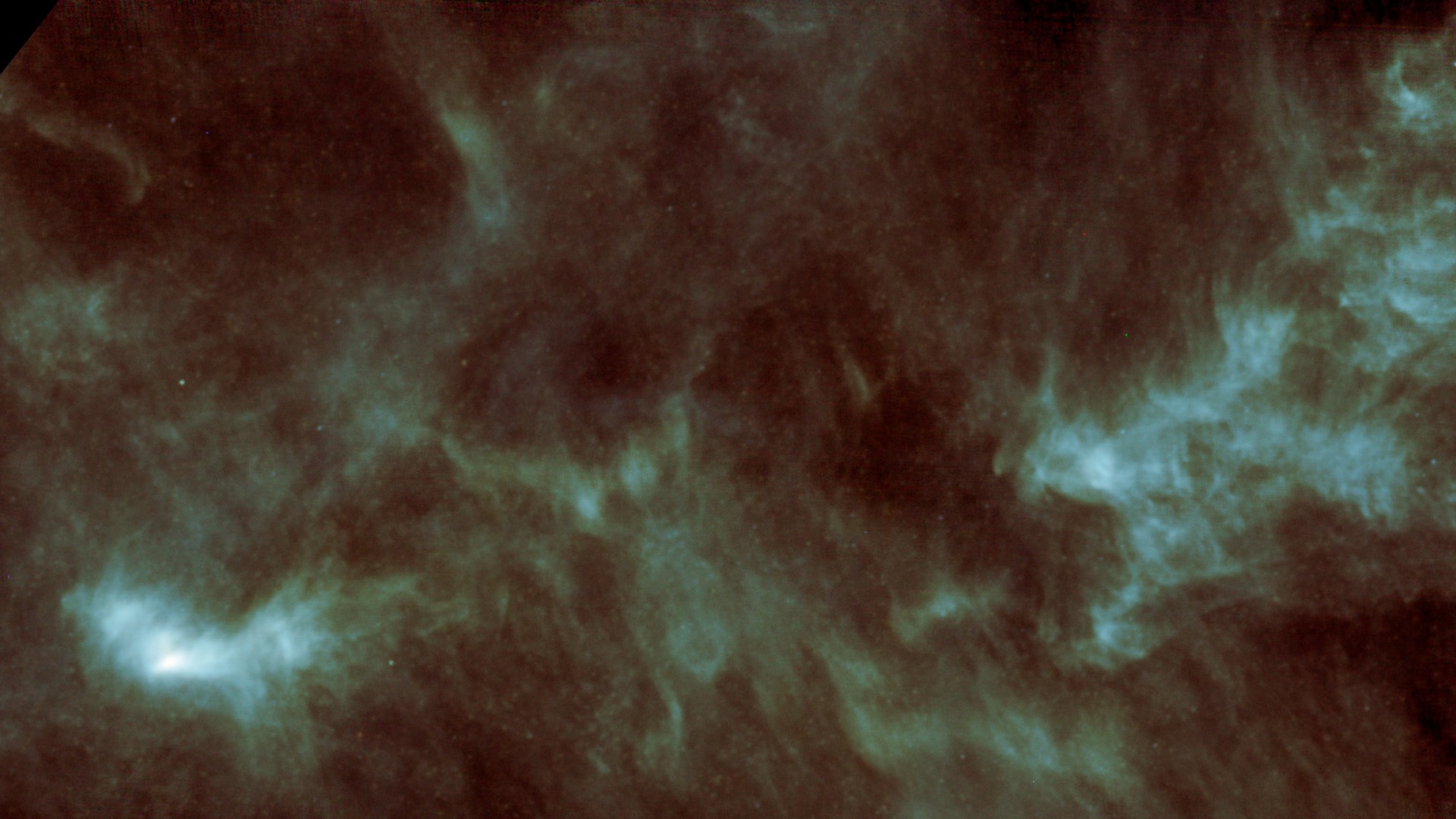

The spacecraft discovered new moons around Saturn; the planet has 53 named moons and another nine unnamed moons, and there are many more small objects that might one day be confirmed as moons. Cassini found geysers erupting from the surface of the large, icy moon Enceladus. Further study of the geysers has since indicated that Enceladus' subsurface water ocean might have conditions suitable for life. Cassini revealed new details about the strange surface of the moon Titan, which is dotted with liquid methane lakes, rivers and oceans.

"We left the world informed but still wondering," Maize said during a news conference Wednesday (Sept. 13). "I could not ask for more."

The $3.26 billion Cassini-Huygens mission — a joint effort by NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency — launched in 1997 and arrived at the Saturn system in 2004. In 2005, the Huygens lander dropped onto the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, revealing the hidden world beneath its opaque, orange atmosphere. The Cassini orbiter's initial mission was meant to last until 2008 but was extended twice, stretching the spacecraft's life to 2017. [How the Cassini Mission to Saturn Worked (Infographic)]

"One of the greatest legacies of the mission is not just the scientific discoveries it makes, and what you learn about, but the fact that you make discoveries that are so compelling that you have to go back," said Mike Watkins, director of JPL. "We will go back and fly through the geysers of Enceladus, we will go back and look at Titan, because the Cassini findings are just groundbreaking."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter