Asteroid Threat: Sizing Up Earth's Vulnerability to Space Rock Strikes

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

A newly announced private space telescope mission aims to reduce Earth's vulnerability to catastrophic asteroid strikes, which the instrument's builders regard as unacceptably high.

The Sentinel space telescope, which the nonprofit B612 Foundation hopes to launch in 2017 or 2018, may identify 500,000 near-Earth asteroids in less than six years of operation — quite a feat, considering that just 10,000 such space rocks have been catalogued to date.

This asteroid-mapping work is vitally important, B612 officials say, because some big and dangerous space rocks undoubtedly have Earth's name on them.

"They have hit the Earth in the past and will do so in the future, unless we do something about it," former astronaut Ed Lu, B612's chairman and CEO, told reporters Thursday (June 28). [Photos: The Sentinel Space Telescope]

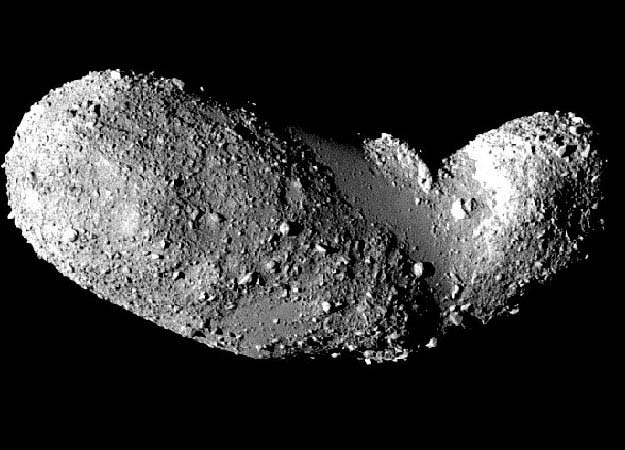

So how vulnerable are we right now to a devastating impact? It varies, depending on the size of the asteroid.

Fortunately, we're probably not going to get smacked any time soon by a potential civilization-killer (anything at least 0.6 miles, or 1 kilometer, wide). Scientists think about 980 of these mountain-size asteroids are zipping through Earth's neighborhood. We've already found nearly 95 percent of them, and none pose a threat to Earth in the near future, researchers say.

But the outlook isn't so rosy for smaller objects. For example, observations by NASA's WISE space telescope suggest that about 4,700 asteroids at least 330 feet (100 meters) wide come uncomfortably close to our planet at some point in their orbits.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So far, researchers have spotted less than 30 percent of these space rocks, which could obliterate an area the size of a state if they slammed into Earth.

And we've found just 1 percent of the near-Earth asteroids that measure at least 130 feet (40 m) across, B612 officials said. Such space rocks could do considerable damage on a local scale, as the so-called "Tunguska event" illustrates.

In 1908, an object thought to be 130 feet wide — or perhaps even smaller — exploded above the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Siberia, flattening roughly 770 square miles (2,000 square km) of forest.

Such monster impacts are a fact of life on our planet. Asteroids big enough to cause major disruptions to the global economy and society (were they to strike a populated area today) have hit Earth every 200 or 300 years on average, Apollo 9 astronaut and B612 chairman emeritus Rusty Schweickart has said.

Giving ourselves a chance

B612 officials want Sentinel to help fill the huge gaps in our near-Earth asteroid catalog.

The telescope, which will scan Earth's neighborhood from an orbit near that of Venus, should spot the few remaining mountain-size space rocks and find 90 percent of the 460-footers and 50 percent of the 130-footers out there, Lu said.

The goal is to detect big, dangerous objects several decades before they may hit us, giving humanity enough lead time to mount a deflection mission. We have a chance, in other words, to avoid the fate of the dinosaurs, which were wiped out by a catastrophic impact 65 million years ago.

"Today, with our technology and with our knowledge, we are able to very slightly but effectively reshape the solar system to enhance long-term human survival," Schweickart said.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.