10 fascinating Perseid meteor shower facts

The Perseid meteor shower dazzles every year.

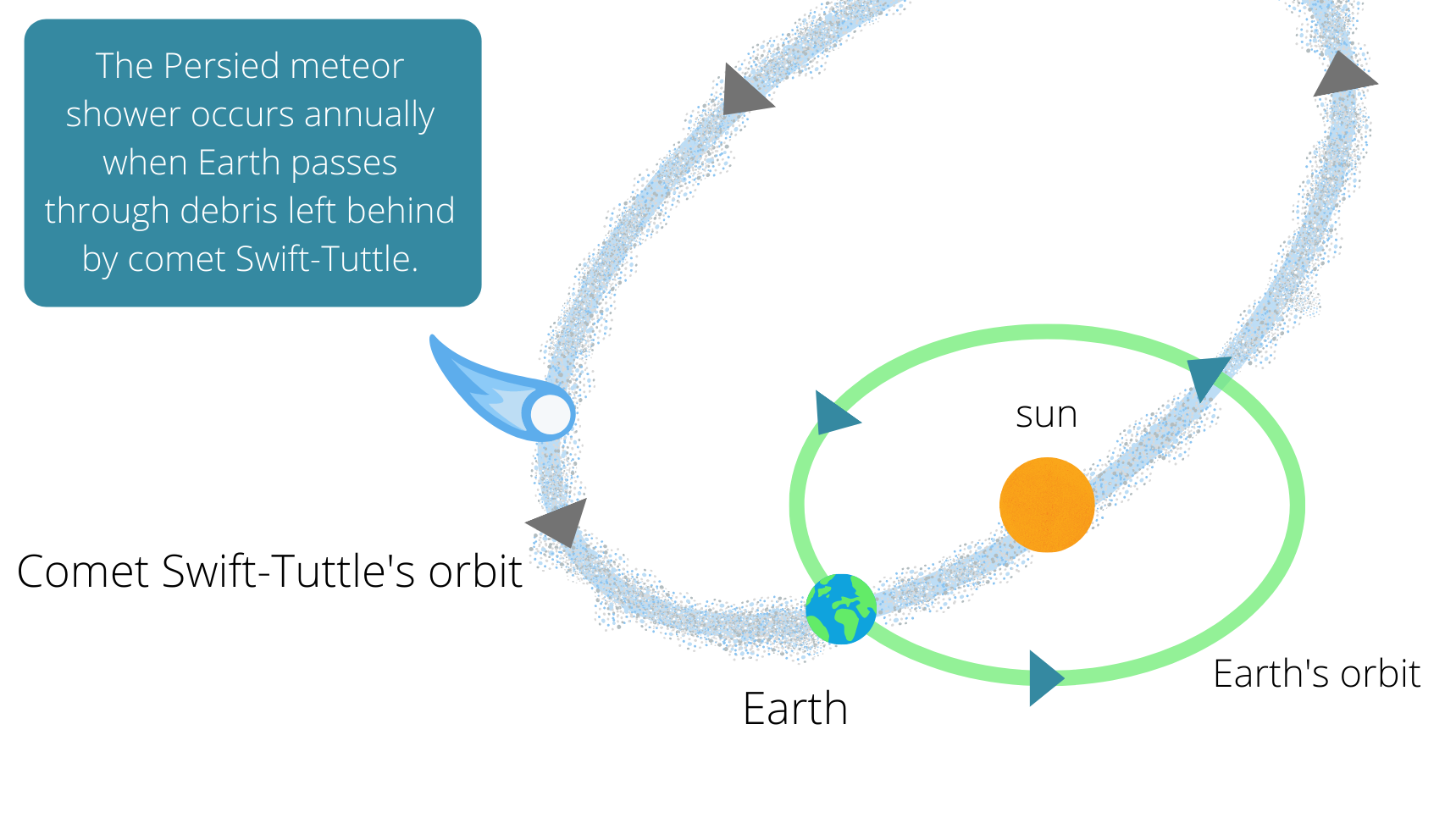

Every August, the night sky is sprinkled with comet debris during the annual Perseid meteor shower.

In 2024, the Perseids will peak on Aug.11-12, with observers under clear, dark skies potentially seeing up to 100 meteors per hour, according to NASA. These meteors are fragments from the comet Swift-Tuttle and often produce the most spectacular meteor shower of the year.

Here are 10 amazing Perseid facts that you can use to impress your friends and family while you hunt for shooting stars.

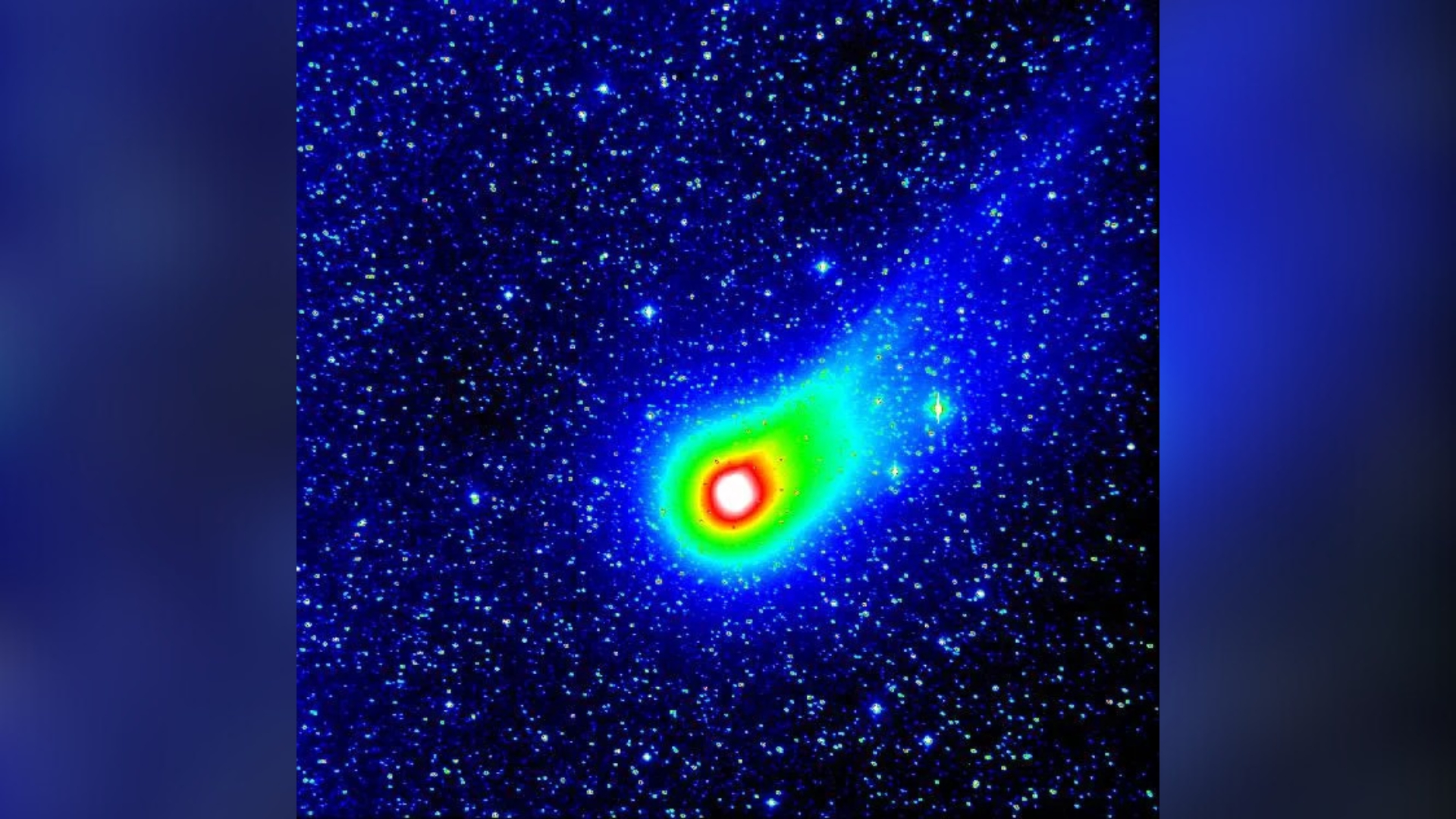

1. Spawned by a giant

Comet Swift-Tuttle, responsible for the debris that creates the Perseids, is the largest known object to repeatedly pass near Earth. Its nucleus measures approximately 16 miles (26 kilometers) in diameter, making it roughly twice the size of the asteroid hypothesized to have caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

2. Comet incoming!

In the early 1990s, astronomer Brian Marsden calculated that Comet Swift-Tuttle might collide with Earth on a future pass. However, further observations soon ruled out any possibility of a collision. Marsden did find that the comet and Earth could have a relatively close encounter, passing within about a million miles of each other, in the year 3044.

3. They don't hang around

Perseid meteoroids, as they're called in space, are incredibly fast, entering Earth's atmosphere as meteors at approximately 37 miles (59 kilometers) per second. Most are the size of grains of sand, but some are as large as peas or marbles. Almost none reach the ground, but if one does it is called a meteorite.

4. Perseids are hot stuff

When a Perseid particle enters the atmosphere, it compresses the air in front of it, which heats up. The meteor, in turn, can be heated to more than 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 Celsius). The intense heat vaporizes most meteors, creating what we call shooting stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

5. Big family

Comet Swift-Tuttle has many cometary relatives, most of which originate in the distant Oort Cloud, which extends nearly halfway to the nearest star. The vast majority never venture into the inner solar system. However, a few, like Swift-Tuttle, have been gravitationally nudged onto new paths, possibly due to the influence of a passing star long ago.

6. High flyers

Perseids begin to burn up about 60 miles (100 km) above Earth's surface. Few (if any) make it all the way down to the ground and become meteorites.

7. A shower of gold

According to ancient mythology, Perseus is the son of the god Zeus and the mortal Danaë. The Perseid meteor shower is said to celebrate the time when Zeus visited Danaë, Perseus' mother, in a shower of gold.

8. Perseids enjoy a long reign

It's possible that you may have already seen a Perseid meteor this year as they are active from mid-July until nearly the end of August. This is because Comet Swift-Tuttle's debris stream is very wide so it takes Earth some time to travel past it.

9. The early bird catches the shooting star

As Earth rotates, the side facing the direction of its orbit around the sun tends to collect more comet space debris as you Earth faces the comet debris head-on. This area of the sky is directly overhead at dawn, making the predawn hours the best time to view the Perseids and other meteor showers, as well as random shooting stars.

10. Comet Swift-Tuttle has been around the block more than once

Comet Swift-Tuttle was last observed in 1992, during a pass through the inner solar system that was relatively unimpressive and required binoculars to view. Before that, it had last been seen in 1862, the year it was "discovered" by American astronomers Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle, when Abraham Lincoln was president.

Editor's Note: If you snap an amazing picture of the Perseid meteor shower or any other night sky view that you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, send photos, comments and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!