Discovery of Earth's Oldest Fossils Could Spur the Search for Life on Other Planets

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

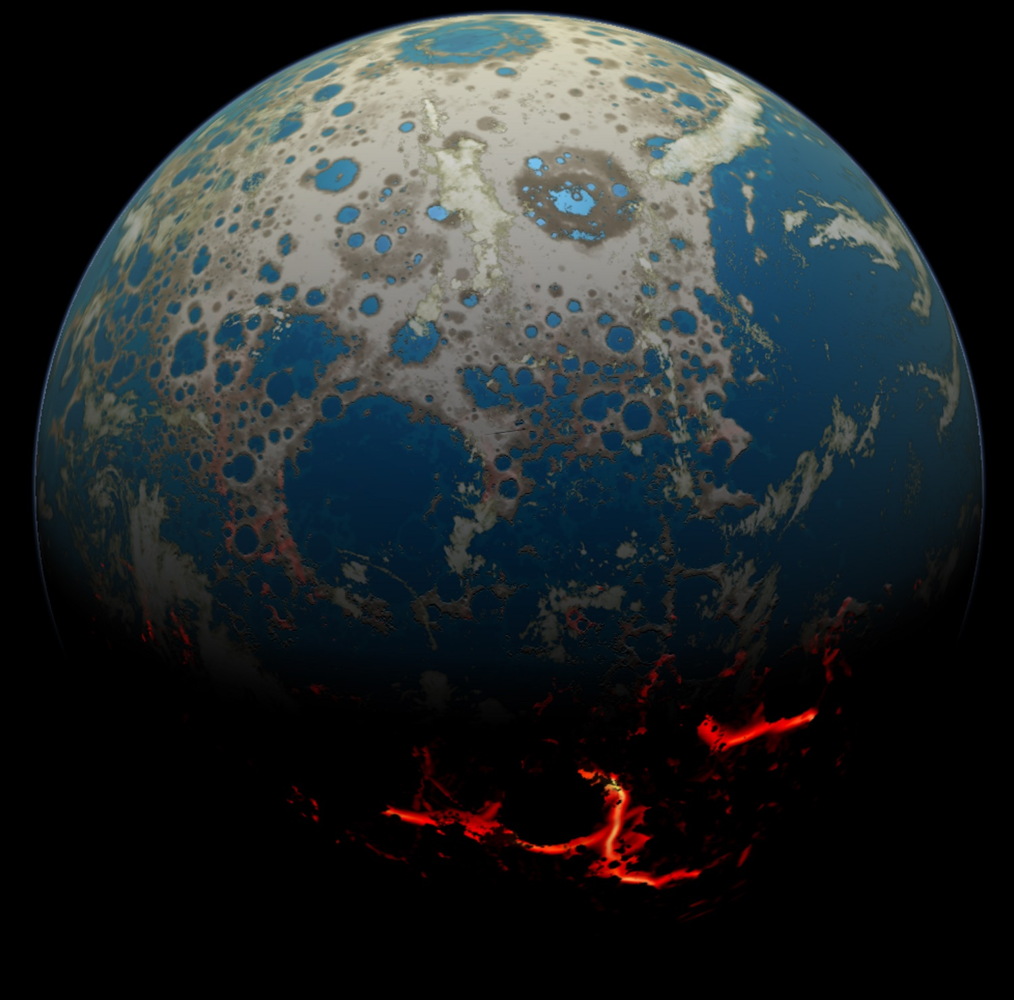

Researchers this week announced the discovery of fossilized remnants that may be the oldest sign of life on Earth, a finding that has implications in the search for life on other planets as well.

Analysis of rock fragments from a rare, primitive piece of Earth's oceanic crust revealed micrometer-sized tubes and filaments believed to be the remains of iron-eating bacteria that lived between 3.8 billion and 4.3 billion years ago. The bacteria are thought to have lived in hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, since the fossilized structures resemble those produced by iron-oxidizing bacteria near hydrothermal vents today.

The find, reported in this week's issue of the journal Nature, pushes back the record of life on Earth to within a few hundred million years of the planet's formation. At that time, Earth likely wasn't the only planet in solar system that could have supported some form of life.

Scientists have amassed strong evidence that Mars also once had pools of water — perhaps even extensive oceans — as well as a thicker atmosphere and all of the chemical ingredients that are necessary for the development of microbial life.

RELATED: Organic Material Discovery Suggests Life Could Exist on Dwarf Planet Ceres

"Unlike Earth, and even Venus, there are significant areas on Mars' ancient surface that are really well preserved and provide great places to search for past habitable environments and the bio-signatures they might contain," said planetary scientist Jeffrey Johnson with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Maryland.

If the new research holds up to the scrutiny of micropaleontologists, "then it provides an analog for sedimentary systems on Mars where we see silica and iron oxide," added California Institute of Technology geologist John Grotzinger.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Grotzinger, the former lead scientist for NASA's Mars Curiosity mission, noted that the rover observed those conditions in what is known as the Murray formation, a geologic layer in Gale Crater that formed from lakebed mud deposits.

"This looks good for Mars," Grotzinger said.

Finding that ancient life thrived in hydrothermal vents also raises the prospect of life in oceans buried beneath thick layers of ice that cover several moons of Jupiter, Saturn and other giant planets in the outer solar system.

RELATED: NASA Injects New Funds Into Search for Origins of Life

Jupiter's Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, for example, are believed to contain salty oceans in contact with rocky cores — the same sort of chemistry and environmental conditions that may have led to life on Earth.

"Given this new evidence, ancient submarine-hydrothermal vent systems should be viewed as potential sites for the origins of life on Earth, and thus primary targets in the search for extraterrestrial life," University College London doctoral student Matthew Dodd and colleagues wrote in their Nature article.

While there is no assumption that life beyond Earth, if it exists, would be the same as terrestrial life, it's a starting point.

"We know how to turn life on Earth into a testable hypothesis," remarked Shawn Domagal-Goldman, an astrobiologist with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, at a NASA planetary sciences planning meeting this week.

"The best-known alien biosphere for which we have data is Archean Earth, the ancient Earth," Domagal-Goldman added. "We now can start to understand how we would look for the signs of life that would have been present on Archean Earth, when there was no oxygen in the atmosphere."

WATCH: There Could Have Been Life on Venus

Originally published on Seeker.

Irene Klotz is a founding member and long-time contributor to Space.com. She concurrently spent 25 years as a wire service reporter and freelance writer, specializing in space exploration, planetary science, astronomy and the search for life beyond Earth. A graduate of Northwestern University, Irene currently serves as Space Editor for Aviation Week & Space Technology.